Terence Blacker: How an LSD trip changed my life for good when I was lost

'Pierre took me to a place where someone on a bad trip should never go, a mazy garden of bushes and paths'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The smile was almost the same. Those heavy-lidded dark brown eyes may have become rather warier over the 20 years since we had last met. The handsome black face was a little more lined, but still conveyed interest, affection, mild amusement.

It was my old friend Pierre’s front teeth that were different. He had none. He was a cycle messenger in New York these days, and had been involved in a nasty accident.

Now he was in Barnes, staying for a few weeks at the house of an older man, possibly his lover, who was arranging for the National Health to fix Pierre’s teeth. It was a case of what we now call “health tourism”.

Although I had not seen him for over a decade, I had not been surprised to get the call from Pierre. He was one of those people who appear in one’s life at the most unlikely moments. The last time we had met, it had been at an intersection on 5th Avenue in Manhattan. I was visiting New York on business as a publisher. As I stood at a pedestrian crossing, I glanced at a lean cyclist waiting for the lights to change and found myself staring into the eyes of Pierre.

We had a brief, astonished conversation. Our friendship dated back to Paris in the early 1970s; how odd it was to run into each other all these years later on another continent. He gave me a telephone number so that we could meet up later but, when I rang that evening, the woman at the other end said she had never heard of Pierre. Whether he had given me an invented number or the woman was covering for him mattered little. He clearly had no wish to see any more of me.

Yet now, in London, he was the one who had contacted me. By this time, I had become a freelance writer. I had written a couple of novels and some children’s books.

We met over tea at his benefactor’s house, and in his rather chilly presence. Pierre’s friend was a civil servant of some kind, and exuded the feline superiority of a Sir Humphrey. I sensed that he did not entirely approve of me, or perhaps he was feeling a touch defensive about the rather dubious activity in which he was involved on Pierre’s behalf.

I brought with me a copy of my first novel, Fixx – a paperback edition which would give Pierre the benefit of seeing on the back cover the rather good reviews the hardback had received. He flicked through its pages, rather disdainfully it seemed to me, and then flashed me a toothless smile. “So this is what you do these days,” he said.

His friend laughed, as if Pierre’s remark had been particularly amusing. “You write to earn a crust, do you?” he asked, and there was no mistaking the sneer in the voice.

It pissed me off. Here were two people whose current project was to rip off the National Health; they hardly seemed in a position to take a patronising view of my faltering efforts to earn a living as a writer. I became huffy, and left soon afterwards, leaving my novel behind to allow them to revise their opinion of me.

Later, though, I felt sad. It would have been good to talk to Pierre away from the company of his creepy friend. We had once been young together in Paris, and he had helped change my life.

We probably met at Shakespeare and Company, then (and possibly now) the hang-out of choice for part-time beats, would-be writers and tourists. Owned and run by a slight, goatee-bearded American called George Whitman, it was a wonderfully shambolic three-storey bookshop on the banks of the Seine.

George, whom I got to know reasonably well, was good at the myth-making side of literary life. He did not go out of his way to mention the fact that his shop had nothing to do with the original, legendary Shakespeare and Company, which had been set up in the 1920s by Sylvia Beach and which had published Joyce’s Ulysses, nor did he strenuously deny the rumour that he was Walt Whitman’s grandson.

All the same, George’s Shakespeare and Company had quite a history of its own. Aristocrats of the hip literary scene – Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, William Burroughs – had read there. Now and then, the cool and charismatic poet Ted Joans, living in Paris at the time, gave readings.

Like many of those who fantasised vaguely about being a writer, I hung out there. It was a good place to meet interesting, or at least like-minded, people. Being there made us all feel slightly more authentic and bohemian than we really were, as if our Paris was not so different from that of Henry Miller and Anaïs Nin. Perhaps we thought we could acquire literary talent by osmosis.

I worked at the shop for a while and slept a few nights on one of the bug-infested beds that were to be found in the book-lined upstairs rooms. More unusually, I was also beaten up there. An American sub-Hemingway type called Jim had swindled me, inviting me to join a group of his friends at a Chinese restaurant and then doing a runner, leaving me to pay the bill. I tried to get my money back by hiding his typewriter, which he kept in an upstairs room at Shakespeare and Company.

It was a bad idea. Jim turned out to be a serious thug who would end up serving a long jail sentence in Indonesia for drug-running. He got his typewriter back.

My friendship with Pierre was altogether happier. He was about my age and, although we were different in nationality, colour and sexual orientation, we immediately hit it off. We were both alone in Paris, bookish and solitary. He seemed to have read everything and had a rather interestingly unfashionable taste in literature and music. He liked Henry James, Edith Wharton, Gertrude Stein, Michel Tournier and a number of French authors of whom I had never heard.

We became pals, and began to hang out together. We went to the marché aux puces, a vast shantytown of antique dealers in the Porte de Clignancourt. We saw Léo Ferré singing at l’Olympia. He introduced me to Ella Fitzgerald singing Cole Porter. I shared with him a rather odd passion I had developed for the choral music of CPE Bach. Mostly, we talked about books and politics and ideas. I was no intellectual, but I was restless and curious, and generally uncertain as to what I was going to do in the world. Pierre was always interesting, often provocative. We would have heated, slightly pretentious rows about our favourite authors.

He was secretive about his life – his family, education, why he always seemed to have money without the inconvenience of doing a job – but somehow none of that mattered. Adrift, in Paris, we had no interest in the outside world. He seemed intrigued by what I told him about myself, and that quietly flattered me.

In a low-key and tentative way, I was on the run from my life, or at least from my background. Although I had been to Cambridge, I had pretty much wasted those three years by pursuing my obsession with riding racehorses. My upbringing had revolved around horses and ponies: my mother was a brilliant horsewoman, my father an international show-jumper. My brother had just become a professional jockey.

After university, I had tried to make a living on the dreary fringes of racing and had ridden as an amateur jockey. I was a stable-to-stable rep for a horse tonic called Equiform at one point. I became involved in a transport firm run by a trainer. I rode out in the early mornings, kept my weight down with variety of unhealthy (now illegal) pills, and travelled to racecourses around the country – Nottingham, Uttoxeter, Huntingdon – often to ride bad horses in insignificant races.

After a couple of years, the penny dropped. This was not my world. There was more to life than horses. Yet the other career options offered to me were unappealing. There was a possible job in the City. My father, at a moment of true desperation, suggested that I might become a policeman.

Running away to Paris was one of my better decisions. In a city where my accent and background counted for nothing, I could wander about on my own. I became entangled in strange and interesting interludes and passing relationships. I worked in a Right-Bank book shop called Galignani and found myself selling books to its distinguished clientele, including Orson Welles, Marlene Dietrich and the Duke and Duchess of Windsor.

Pierre was part of all that, and gave me confidence. He was amused, with some justification, by the idea that I had been an amateur jockey. He sensed, quite rightly, that I was lost in my life. He was cooler than I could ever be, speaking fluent French and apparently at complete ease in a foreign country.

His gayness, in those early days of our friendship, was never an issue. Now and then, he would disappear for a few days, returning in a slightly subdued state. He alluded vaguely to his own adventures in a particular part of Paris, but showed no inclination to tell me more. That was something of a relief.

Then, at some point, he began in a casual, jokey way to put the moves on me. I should try guys, he said. I’d like it.

Pierre’s interest in me was not the slightest bit alarming – I had spent much of my life in single-sex boarding-schools, after all. I may not have known much about myself, but I did know that I wasn’t gay. It became a gentle joke between us. He was the liberated American in touch with his desires; I was a typical uptight Englishman. One day, he said, I would see the light.

Late one evening, he went further. We were at his flat, and he mentioned casually that he had bought a couple of pills. They could have interesting effects, he said. It could be fun.

I was not particularly interested in drugs. I has smoked pot at Cambridge, often alone in my room, making myself rather sick until I got into the swing of it. I had once quite enjoyed some magic mushrooms at a party.

A little pill: what harm could that do? Pierre was worldly enough, I thought, not to have bought dodgy gear. It was probably some mild mood-enhancing thing. We took the pills.

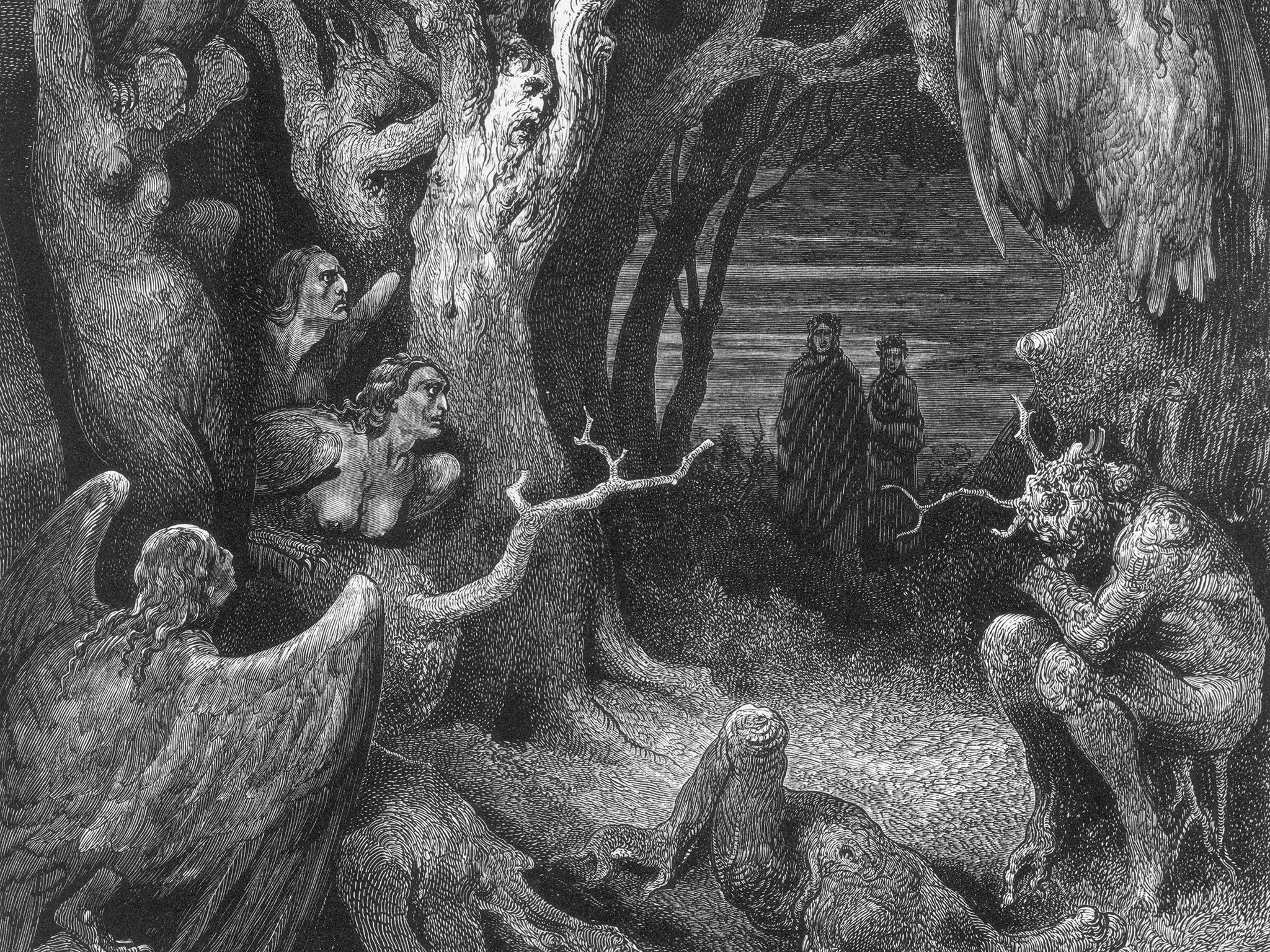

Quite soon afterwards, I was aware that I was beginning to feel strangely anxious. Pierre was smiling and talking to me but what he said made less sense than it should. He seemed both distant and yet, weirdly, too close for comfort. The more he talked, the more convinced I became that he wanted to do me harm. On his wall was a Gustave Doré illustration. Out of the corner of my eye, I noticed that the figures moved. I stared at it more closely. Yes, they definitely moved.

Pierre was disappointed that I was having less fun than he had anticipated. Remarkably clear-headed himself (I wonder now whether he had actually taken his pill), he suggested that we both needed some fresh air. When we walked down the street, the passers-by seemed monstrous and frightening. They all stared at me. They could tell I was tripping. Their heads changed shape as I walked towards them. The voices around me were deafening, but incomprehensible.

Late in the evening, he took me to a place where someone experiencing a bad trip should never go – a mazy garden of hedges, bushes and paths in the Jardin de Tuileries just in front of the Louvre. I had walked past it many times during the day; by night, it was a gay pick-up spot.

It seemed deeply frightening at the time, but in truth men were simply wandering about, looming up out of bushes and around corners with a hopeful look in their eyes. One glance at my freaked-out features was enough for them to move right along.

I fled, followed by Pierre. He took me back to his apartment where he told me that he had given me the pill to relax, to get in the mood. Tonight was to be the night.

It wasn’t. Never had I felt less in the mood for anything. I just wanted to go home. Eventually, as my head cleared in the early hours of the morning, I did.

It was the end of our friendship. Giving someone drugs in order to seduce them is not a good basis for any relationship. I now distrusted Pierre and he, I suspect, had given me up as a lost cause. I was never going to swing his way.

We drifted out of each other’s lives, and not soon afterwards I returned to London and took up a job in publishing.

Memory tidies up the past. Looking back, one imposes a shape on disordered events: this happened, which led to that, and then the other, as a result of which I ended up here. The confusions, uncertainties and blundering wrong turns are edited out.

My first, and only, LSD trip was in reality no more than one of the foolish, mildly rash things I did while living in Paris. Now, though, it seems like a sort of turning point. It was the moment when I discovered that I am not, after all, one of life’s great adventurers. The excesses and eccentricities of the authors I liked to read – Burroughs, Hubert Selby Jr, Frederick Exley – were not something I had the nerve, or perhaps the taste for self-destruction, to experience at first hand.

I was one straight Englishman – a sipper, a sampler, a sidelines man. Not for me the bold journeys across oceans of experience to the wilder shores of this or that; I was content to take a trip around the bay, and then go home.

Maybe that was what Pierre saw, years later in a sitting-room in Barnes, as he glanced through the pages of my novel and said, with that sweet, pitying smile, “So this is what you do these days.”

Terence Blacker’s novel ‘The Twyning’ is published by Head of Zeus.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments