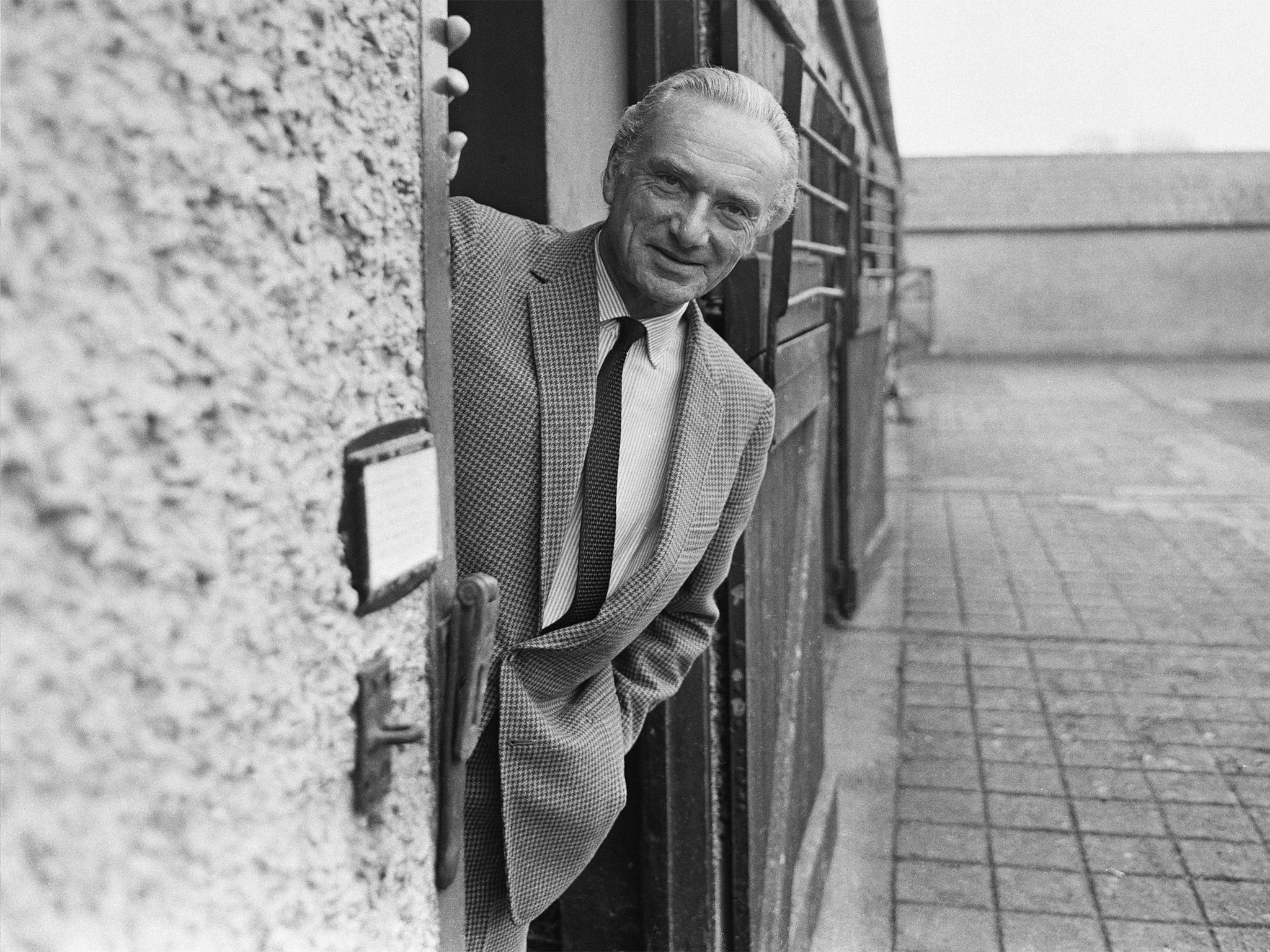

Sir Peter O'Sullevan: Much-loved broadcaster and journalist who was the BBC's voice of racing for more than six decades

O'Sullevan led an extraordinary life, both on the Turf and beyond

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Sir Peter O'Sullevan's voice provided the soundtrack to horse racing for more than six decades. His commentaries, whether at the Grand National, the Derby, or during wet afternoons at the gaff tracks, had a distinct air of hard-earned authority as he called home the greats such as Arkle, Red Rum, Desert Orchid, Sea Bird, Nijinsky, Dancing Brave. He became a legend himself and led an extraordinary life, both on the Turf and beyond.

The sportswriter Hugh McIlvanney said of O'Sullevan: "Had he been on the rails at Balaclava he would have kept pace with the Charge of the Light Brigade, listing the fallers in precise order and describing the riders' injuries before they hit the ground."

Another broadsheet writer remarked that the voice had a mellifluous beauty, and mused: "The sound of Sir Peter calling the horses should be one of our exports into outer space to signify the depth of our civilisation." That last bit gets somewhat carried away, something that O'Sullevan himself would never do, at least not on air. His style – perhaps best once characterised as a "hectic drawl" – remained grounded, focused on the specifics of the action. He knew a horse race was serious business, that money was staked on the outcome. That money often included his own.

There were good days and bad days on the O'Sullevan betting front. One notably woeful afternoon came when he was part of a well-organised but doomed coup on a French-trained horse named Dornot in the Manchester November Handicap, just after the Second World War. At a post-race party things turned very much for the better, however, when O'Sullevan started dancing with a woman. He was to write later: "Had Dornot won I would have flown back to Paris for a celebration, returning on Sunday. And I would never have met Pat, my wife."

When working on BBC radio or TV broadcasts (51 years), or writing for the Daily Express for 35 years (a time of that paper's heyday), O'Sullevan never showed a trace of conceit, was invariably frank, had friends from all walks of life (the Etonian, horse-breeding high Tory Jakie Astor called him "Peter O'Socialist"), and built a formidable array of contacts to help inform followers of his Express copy and tips, and his own wagers. His inside knowledge of work on home gallops, trainers' plans, jockeys' opinions, news from the big training centres in Britain, Ireland and France, was often ahead of even the bookmakers' intelligence networks.

He was very loyal to friends, as revealed in a story about Lester Piggott. In 1987 it emerged that the nine-times Derby winner had been cack-handedly hiding earnings from the taxman, using Swiss and Cayman bank accounts – replicated today in more sophisticated manner by Britain's elite tax evaders. Piggott was given a three-year prison sentence and was later stripped of his OBE. The jockey was particularly hurt by this latter move. O'Sullevan also thought it was not right, that there had been mitigating circumstances. It rankled.

While sitting next to the Queen at Windsor sometime later, O'Sullevan decided to express his feelings on the matter. Recounting the occasion to a Daily Telegraph interviewer in 2014, he said: "So I thought this was an opportune moment, and launched into my Lester spiel to Her Majesty, who put down her knife and fork, and looked at me quite seriously for a moment.

"She put down her knife and fork, as I say, and said: 'I Iike the way you put it, but he was rather naughty, you know. He was not only rather naughty, but he was very stupid, because he paid it [his tax bill] on a bank that hadn't come up in the case, and hadn't been investigated.' "

Devotion to attempting to deprive bookmakers of their cash had developed from a love of horses, having first sat on one at the age of two. He was born in Co Kerry in 1918, the son of a Killarney magistrate and an English mother. After his parents separated he was brought up from the age of six by his maternal grandparents in a country house in Surrey.

At 10, he caused a scare in the locality when going missing after his pony had been turned out of its box, because of visiting horses, and put in a distant field during pouring rain. The boy's absence was reported to the police and a search began. Two hours later a child was found close to the Reigate road, holding an umbrella over a pony.

Soon after, he placed via a local butcher a sixpence each-way bet on Tipperary Tim in the 1928 Grand National. It won at 100-1. O'Sullevan went on to Charterhouse School and was also sent to a college in Switzerland for health reasons. He suffered prolonged illnesses (pneumonia four times in total, chronic asthma, plus a skin condition). All this blighted his childhood, but he never let illness deter him then or as an adult. Of his dermatological problems, he said his extensive experience among numerous skin specialists had led him to the conclusion that "they are as helpful as a welshing bookmaker". Usually, as a young racegoer, he would avoid the grandstands.

In 1939, unfit for military service, O'Sullevan bought a car and helped evacuate families from London to the country. He joined the Chelsea Civil Defence Rescue Service, recalling later: "The first body I helped carry from an air-raid shelter that had received a direct hit was a young girl, whose right hand showed that she had one finger left to varnish when the bomb struck."

Towards the end of the war, O'Sullevan was given a greyhound by a fellow rescue service member. The dog's pet name was Slim and he was often taken to tracks like Staines by public transport. One evening Slim had two toes amputated by a vet following a nasty accident on the Underground, at the foot of a moving staircase. Remarkably, Slim continued winning after that – though only when running from Trap 6.

Horses, though, were the first priority. Knowledge of racing was proven in a trial following a job interview with the Press Association's Fleet Street racing department, where he began working in October 1944. He started working for the BBC in 1946, with his first Grand National radio commentary in 1947.

In 1950 he joined the Express, and a year later married Canadian-born Pat. Nine years after that he commentated on the first televised Grand National, won by Merryman, retaining his usual composure despite winning more than £1,000 on the result. Indeed, O'Sullevan always insisted he was not a gambler, only betting with money he could afford to lose.

His career was helped by a remarkable memory for detail and by being a brilliant storyteller. His autobiography Calling the Horses has been reprinted numerous times and is bursting with the energy of the Turf. It is one of the best sports books ever written. As well as being very funny, it is essential reading for anyone who likes a bet. Here, the dangers and costly blind alleys are well depicted.

He campaigned against overuse of the whip by jockeys, and those who rode the horses he owned – most successfully the magnificent sprinter Be Friendly, or the fine stayer and hurdler, Attivo – were fully aware of that.

For the last two decades, his considerable energies were directed to charity work. In 1997, the year he was knighted, he set up the Peter O'Sullevan Charitable Trust, which has since raised more than £3.5m with the help of animal lovers, racing people and from sales of his autobiography. He continued the fund-raising despite being badly hit by Lady Patricia's death in 2009. Funds are distributed equally between the Thoroughbred Rehabilitation Centre, Racing Welfare, Blue Cross, Compassion in World Farming, the Brooke, and World Horse Welfare.

CHRIS CORRIGAN

Sir Peter O'Sullevan, broadcaster and journalist: born Kenmare, Co Kerry 3 March 1918; Kt 1997; married Patricia Jones (died 2009); died 29 July 2015.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments