Recep Erdogan profile: The President of Turkey... who would be sultan

He promised Turkey a hopeful merging of Islam and modernity. Now he is becoming an all too familiar autocrat

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

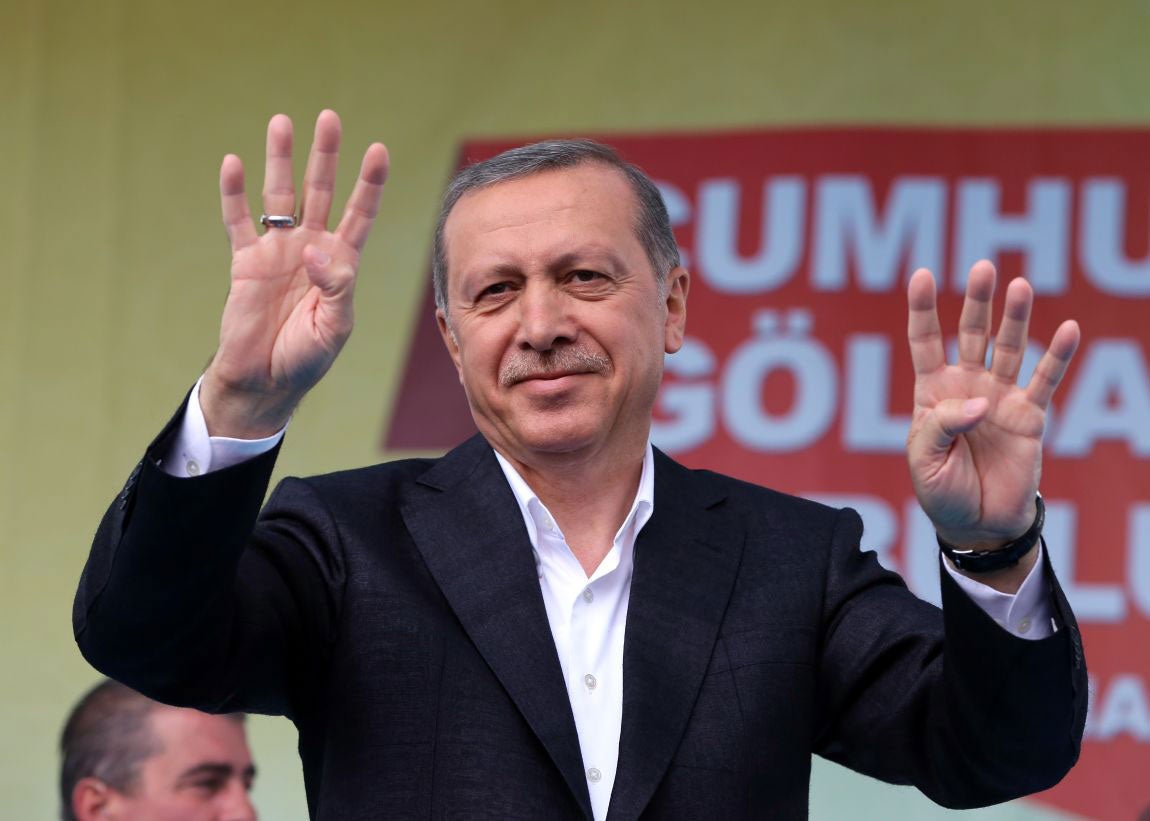

Your support makes all the difference.Tall and slim, still with a full head of hair at 61, President Recep Erdogan has survived 12 torrid years at the apex of Turkish politics with little obvious damage. His chin is smooth, his uniform the same sombre suit and tie he has always worn; nothing about his appearance would cause one to doubt that this was a modern, secular politician, playing by the same rule book as the men in Brussels, who in recent memory were eager to install his nation among the EU’s stars.

His look is unchanged from the great occasion three years ago when President Barack Obama, paying his first presidential visit to a Muslim country, described him as one of his five closest international allies and hailed him as an example of how a leader could be Islamic, democratic and tolerant all at once.

But today this smooth and solemn man has a different message. On a platform in his native Istanbul last Saturday, as hundreds of thousands of Turks watched fighter jets paint the national flag with coloured smoke in the sky, he celebrated the anniversary of the overthrow of Christian Byzantium by Muslim armies and the creation of the Ottoman Empire, 562 years ago.

For his millions of adoring supporters, Erdogan’s achievement is to have reunited Turkey with the Islamic heritage that Kemal Ataturk ditched in the name of modernisation. Quoting from the Koran, he shouted defiance at those who resent his assault on Turkey’s secular tradition. “We will not give way to those who speak against our call to prayer!” he vowed. “Allahu Akbar!” the crowd responded.

The storming of Constantinople was a conquest, he said – one to which his own achievement as modern Turkey’s long-serving leader was comparable. “To reverse this nation’s ill fate for 12 years is a conquest. To successfully pass this turning point on the way to a new Turkey is a conquest,” he told the crowd. “Inshallah, 7 June will be a conquest.”

The “conquest” in question tomorrow will be the winning of enough parliamentary seats by the party he founded, the Justice and Development Party or AKP, to change the constitution, allowing him to transform the ornamental presidency he has occupied since last August into an executive one. This, in turn, will allow him to rule – with far fewer constraints – for another 1o years. It is an ambition that is profoundly polarising.

Recep Tayyip Erdogan has never made any bones about his Islamic piety. He was raised in an observant family in Istanbul and his faith was reinforced at religious high school, and he brought it into his first experiment in politics, as a prominent young member of the Islamist National Salvation Party. But back in the 1970s, the secularist rules imposed 50 years before by Ataturk, designed to drag Turkey into the modern world, were still all-powerful; challenging them seemed the guarantee of a career on the lonely and powerless margins.

But after the Islamic revolution in neighbouring Iran, the mood around Islam and politics began to change. Erdogan was elected to parliament; prevented from taking his seat, he stood instead for mayor of Istanbul and won. Opponents feared he would clamp Sharia on Turkey’s most freewheeling city; instead he disarmed critics by proving a resourceful and energetic executive, taking drastic and effective measures to transform its rubbish collection, public transport and water supply. But his fundamental passion was unchanged.

In 1997, the fundamentalist Welfare Party to which he now belonged was threatened with closure for being unconstitutional, and Erdogan, still the city’s serving mayor, took to the streets to demand that the authorities leave it in peace. “The mosques are our barracks,” he recited at one demonstration, “the domes are our helmets, the minarets our bayonets and the faithful our soldiers.” For that he was arrested, convicted of incitement to religious violence, and sentenced to 10 months in jail, of which he served four months. With Turkey’s secular establishment under steadily increasing pressure from the rising tide of Islamism, the sentence caused him no lasting damage.

And Erdogan’s twin faces – his sincere and unabashed piety on the one hand, his technocratic flair as a modern administrator on the other – placed him in pole position to lead a country increasingly restless under the old Ataturk rules.

Founding the Justice and Development Party in 2001, Erdogan cruised to a landslide election victory the following year, and after several bruising rounds with a secular establishment desperate to keep him down, became Prime Minister for the first time in 2003.

Coming to national power in the wake of a financial crisis that forced the country into an International Monetary Fund bailout programme, he re-affirmed his skills, transforming Turkey’s economic prospects, turning it into a major exporter with Chinese-style growth rates of up to 8 per cent. He succeeded in forcing the military – secular through and through – out of its hidden but powerful role in politics, and used his position of unrivalled power to do what no Turkish politician had previously dared: to put out olive branches to the 15 million-strong Kurdish minority concentrated in the south-east, initiating peace talks.

But his 12 years at the top have had a disastrously inflationary effect on Mr Erdogan’s ego. The most obvious symptom of this is the presidential palace recently completed in Ankara for a sum in excess of $600m, said to include a laboratory where a team of scientists works day and night ensuring that the President is not poisoned. The palace, 30 times the size of the White House, has more than 1,000 rooms. It may also have gold-plated fixtures in the bathrooms – though when a rival politician mentioned it, Mr Erdogan sued for slander.

His pharaonic tendencies have also seen him become increasingly authoritarian, lashing out with threats and law suits at those in the media who attack him, closing down social media, and sending riot police to disperse demonstrations against the building of a shopping mall in Istanbul’s Taksim Square. That provoked far more widespread protests against him. He responded with increased police powers and heavier penalties for illegal demonstrations.

His Islamism, his growing authoritarianism and his ever-increasing sense of his own importance are the reasons why many fear that if AKP wins 60 per cent of the seats in tomorrow’s election, enabling him to push through constitutional reform, Turkey could become “the land of Erdogan”, with its fragile democratic traditions increasingly under threat.

The one bright hope of that not happening is, ironically, the man whose rise to prominence came through Erdogan’s attempt to bring Kurds into the national mainstream. Selahattin Demirtas is the leader of the People’s Democratic Party or HDP. Although its bedrock support is Kurdish, it is hoping to attract mass support from those frightened and alienated by Erdogan’s bid for total power. Rules devised to keep the Kurds on the sidelines mean that HDP must pass a threshold of 10 per cent of support to get into parliament at all. If they succeed, Erdogan’s hopes of rewriting the constitution will be greatly weakened; and the land of Erdogan, for which many yearn but which many dread, will remain a long way off.

A life in brief

Born: 26 February 1954, Istanbul, Turkey.

Family: Father Ahmet Erdogan, was a coastguard. Married to Ermine; they have four children.

Education: Islamic school in Istanbul before graduating from Marmara University with a degree in management.

Career: Mayor of Istanbul, 1994-98. Founder of JDP, Islamic Truth and Development Party, 2001. Prime Minister of Turkey, 2003-14. In 2014, he became the country’s first directly elected President.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments