Passed/Failed: An education in the life of Professor Heinz Wolff, scientist and broadcaster

'I made toffee in a test tube'

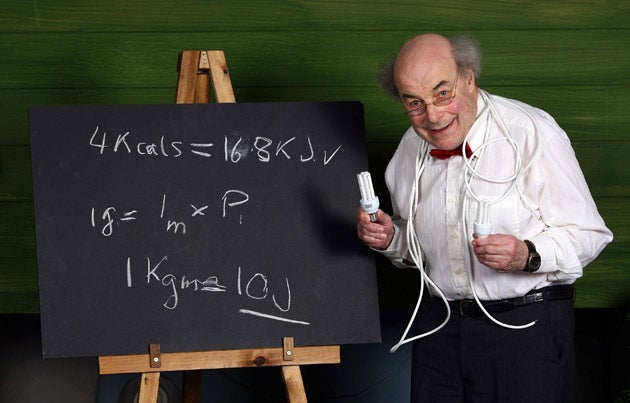

Heinz Wolff, 81, is the world's first bio-engineer and the founder of the Institute of Bio-engineering at Brunel University. His television and radio work includes The Great Egg Race on BBC2. He has launched "Britain's Bright Ideas", the npower competition for the best energy-saving inventions (www.npower.com/ brightideas) which ends on 30 June).

I was born in Berlin and can remember at four years old standing in our fourth-floor flat and seeing the torchlit parade of Hitler's Brownshirts. Jews were not allowed into state – that is, non-Jewish – schools and in I went to the Jüdische (Jewish) Waldschule Grunewald school. It was a highly civilised school and I jumped up a form. I didn't do science at school before I was 11 but my father still had his boyhood laboratory set and on Sunday afternoons we would do chemistry. I still remember putting sugar into a test tube, crystalising it and making toffee.

I came to this country on 3 September 1939, the day war was declared, and went to a mixed prep school in London for eight months. I was classified as an enemy alien and was at school with people whose brothers and fathers were being killed by Germans – but at no stage was it ever held against me. I don't believe there is another country where this would have happened.

Then I went to an "elementary" school in Oxford until there was room for me at City of Oxford, a grammar school. It was very good for science and I was very happy. There was an enormous amount of ex-War Department equipment which schools could buy – £1-worth for a penny – and I persuaded my school to buy an "Aladdin's cave" of electronic components.

I had a place to study chemistry at an Oxford college but one morning I got a postcard saying, "As there are ex-Servicemen coming back, would you be prepared to postpone your place for a year?"

I got myself a place as a technician at the department of haematology at the Radcliffe Infirmary in Oxford under Robert MacFarlene, who discovered an anti-clotting substance called anti-haemophilic globulin, partly using samples of my blood. At the time there was a major problem with counting red blood cells. I thought of a relatively simple way of mechanising the blood count.

The Medical Research Council had a problem with ways of estimating the dust exposure of men working in mines and I was given a job to work on this. I ended up at University College London and read physiology. In my first summer vacation I worked at King's College, London with the losing team in the race for the Double Helix [the structure of DNA was discovered by Cambridge's Watson and Crick].

In my second vacation I worked at the National Institute for Medical Research and devised a machine which measured how much energy an individual uses. I got a First. In my Finals I was able to quote my own publications. Old engineers and scientists become philosophers. My motivation is: wanting Britain to be as self-sufficient as possible. I have launched npower's competition for people with good ideas on energy conservation. One of the things I would suggest is heated underwear – and I have made such a thing.

My wife knitted underwear out of flexible wire to measure skin temperature; sending a current through it instead would heat the skin. In a store you would ask for a 10-ohm shirt rather than one with a size 16 collar. Also, I was cooking eggs earlier today in a demonstration using some of my energy-saving equipment. Two pages of The Independent give the energy for a nicely soft-boiled egg.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks