Passed/Failed: An education in the life of Michael Mansfield QC

'The teaching for the Bar exams was simply dreadful'

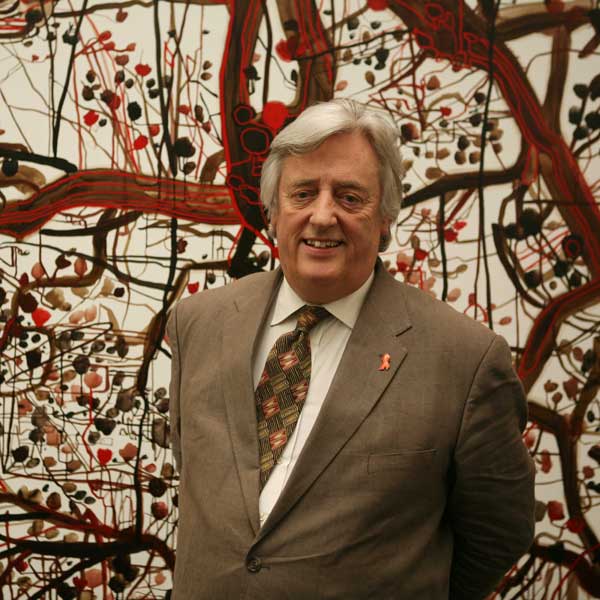

Michael Mansfield, 68, has been involved in many controversial appeals, inquests, inquiries and trials, including cases involving the Birmingham Six, Princess Diana, Jill Dando, Stephen Lawrence and Jean Charles de Menezes. His book, Memoirs of a Radical Lawyer, came out last year. He is a member of the Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation's Russell Tribunal on Palestine.

I seemed to get "keen and attentive" in my reports; it probably meant "not very good, but at least he turns up". I remember enjoying Holmewood, a private, co-ed school in North London, but I once had an awful report for regularly banging shut my desk lid.

I managed to pass the Common Entrance to Highgate Public School. It threw up eccentric, free-thinking teachers. The history and politics teacher, TN Fox, who reminded me of Tintin with his wisp of curly hair, would take off his socks when they got wet in winter and hang them on the radiator. He would open the lesson by asking questions. "What do you think about passports, Mansfield? Should we have frontiers?" I never dreamt that I could speak in public, but he told me that I had the necessary mental equipment.

I did history, English and politics A-levels. I had a very close friend who had the same results as me. He got into Keele University and I didn't. When he went there at the end of September, I discovered where the admissions tutor lived, got on a train, knocked on his door and said: "I want to come."

It was Sunday lunchtime. He said: "Come and join us for lunch." After we had the gooseberry fool dessert, he said: "I'll interview you now. I have only one question. What would you do with a £1m?" I said: "I would give half to my mother and set off round the world by myself and I wouldn't come to university." He said: "You're in." "When do I start?" "Now." I'd brought a bag containing all my things with me.

Keele had a brilliant and broad system of education. You had a foundation year in which each week you would be going to lectures and tutorials in a new subject, from astronomy to zoology. At the exams at the end of the year, my friend, instead of answering the questions, spent the three hours saying that examinations were not a sensible way of testing your thinking power. He failed.

I did history and philosophy. Overall, I got a 2:1, but I got a first for my philosophy. Professor Antony Flew, who ran the department, said: "I never thought you would get a first, but you worked very hard." He was a larger-than-life, mammoth of a person, a towering intellect, a taskmaster: there was no way you could drift. He died in April. I once had the chance of cross-examining him when I was on the panel of [the Radio 4 programme] Moral Maze. He came on as a witness.

The teaching for the Bar exams in London was simply dreadful. As a barrister, you do need practice in presenting your arguments, but there was no practical training, though the Inns of Court had "Moots", which are mini-mock-trials. They were useful. Teaching was totally parrot-fashion. You'd go to a lecturer, who would stand up and just read out a prepared talk – probably the same one that he gives every year. We said: "Why don't you just give us the text and we can read it?" I had to keep doing retakes until I felt like a crammed parrot.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks