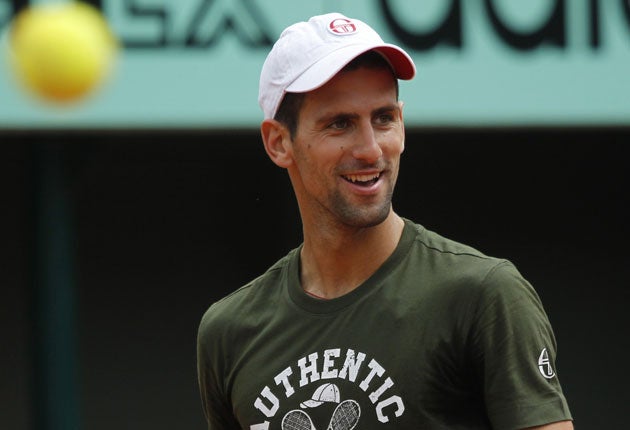

Novak Djokovic: Mr Unstoppable

As a child, he didn't let the bombs that fell on Belgrade keep him off the tennis court – and now that determination has taken him on an unprecedented run of success. Does his rise mean the end of the Federer/Nadal era?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.While tennis is all the rage in Serbia, sales of bread and cakes are doubtless wobbling.

Novak Djokovic, the country's transcendent sporting superstar, has not only broken the duopoly in men's tennis of Roger Federer and Rafael Nadal, which has for so long seemed inviolable, but has done so on a gluten-free diet. And has done so, moreover, with charm, charisma and humour.

Djokovic's on-court impersonations of other players, not least Nadal's habitual fiddling with the seat of his pants, have delighted fans of what is so often a po-faced game. The Serb is not averse to throwing and smashing his rackets when the mood takes him, but like Federer and Nadal before him, he is impossible to dislike. Not since Athos, Porthos and Aramis represented the King's musketeers have three such formidable but approachable ambassadors arrived in Paris, where the French Open begins tomorrow, the day Djokovic turns 24.

That some bookmakers make Djokovic a narrow favourite to win the second of the year's four Grand Slam tournaments (the Australian and French Opens, Wimbledon and the US Open) is in itself remarkable. Because even though Djokovic won the first, in Melbourne in February, it is the mighty Nadal who traditionally bestrides the clay courts of Roland Garros in Paris.

Nadal has won five of the last six French Opens, his extraordinary dominance punctured only by Federer. Between them, the Spaniard and the Swiss have won 21 of the last 24 Grand Slam events. And yet the hot streak that everyone in tennis is talking about belongs to Djokovic.

He has started the 2011 season by winning all seven tournaments he has entered, beating Nadal in four consecutive finals, the most recent of them in Madrid, on clay. Outplaying Nadal on Spanish clay is like mastering Rembrandt in Dutch oils, practically enough to throw the earth off its axis.

And to claim those seven tournaments Djokovic has had to win 37 consecutive matches, a consistency of excellence unrivalled since John McEnroe started the 1984 season with 42 straight wins.

Should the Serb now prevail in Paris, he will surpass McEnroe's feat. It is already a more notable achievement, according to the New Yorker himself, who never dishes out praise where it is not due, and often stints even when it is. "Given that there's more competition, more athleticism and deeper fields now, I'd say his record is even more impressive than mine," reflected McEnroe this week.

Whatever, Djokovic is in danger of leaving our own Andy Murray floundering in his slipstream as he accelerates towards his goal of becoming the first world No 1 since Andy Roddick in February 2004 without a first name beginning with R. Murray and Djokovic, just a week apart in age, are friends and occasional practice partners. In their teenage years it was hard to say which of them would rise the higher. Yet in the final of this year's Australian Open the Serb made the Scotsman look decidedly ordinary.

Murray can perhaps take heart that Federer, who beat him in his only other Grand Slam final, the 2008 US Open, is at last approaching the downslope of an astonishing career, but the explosive ascent of Djokovic, not to mention Nadal's enduring presence at the summit of the game, must fill him with apprehension. It could just be that as very good as he is, the supreme misfortune of his career is to coincide with those of three of the greatest players of all time.

Such a claim cannot yet be made of Djokovic, not quite, not with only two Grand Slam titles (the Australian Opens of 2008 and 2011) to his name. But McEnroe is but one of many experts who sees no reason why the Serb can't become a player for the ages: he has all the shots, combined with sometimes mind-boggling athleticism. And a manifestly fierce will to win.

That will was forged in what, to say the least, were pretty challenging circumstances. Even while Nato bombs were being dropped on Belgrade in 1999, the 12-year-old Djokovic was practising on the beleagured city's tennis courts. It was his rigorous routine, he later recalled, which gave the whole family purpose (he has two younger brothers), and kept them sane.

He would later recall that the tennis court "wasn't any more or less safe than any other place in the street, but if you're sitting at home in the basement, thinking they are going to bomb your home, you're going crazy. We were practising all day, and at seven o'clock we would go home and sit with the curtains closed, everything dark the way it had to be".

Earlier in his life it had seemed more likely that he would follow in the ski tracks of his father, Srdjan, a Yugoslav international skier, who went on to open a pancake restaurant in the mountain resort of Kapaonik. His mother Dijana, meanwhile, came from a talented volleyballing family. Neither parent played tennis, which in the former Yugoslavia wasn't a particularly popular sport. It is now, of course. Indeed, even the country's basketball courts are reportedly overflowing with children playing tennis, improvising without a net, trying to emulate their hero.

Djokovic came under the tennis spell himself when four courts were built opposite the Kapaonik restaurant, and he insisted on having a go. Jelena Gencic, who ran the lessons there, and is still cited by Djokovic as his greatest sporting influence, tells an enlightening story about the first day he crossed the road to play. "He arrived half an hour early with a big tennis bag. Inside his bag I saw a tennis racket, towel, bottle of water, banana, wrist bands, everything you need for a game. I asked him, 'Who packed your bag, your mother?' He said 'No, I packed it'. He was only five. I said: 'How did you know what to pack?' And he said, 'I watch TV'."

In those days, Djokovic's tennis-playing idol was Pete Sampras. The brilliant American rarely gave anyone a glimpse of anything that might be confused with charisma, but watching intently on television, even at the age of six or seven, the little boy clocked the way Sampras handled pressure, the way he served aces at the most pivotal moments. It was all stored up for future reference. And of course, that is where Djokovic's impersonation skills were born, on the family sofa, gazing at people who would one day know his name as well as he knew theirs.

Among those in his repertoire of impressions is JP McEnroe. Djokovic loves apeing the notorious McEnroe temper, and that distinctive left-handed serve – like somebody trying to serve around the corner of an imaginary building, as Clive James once so splendidly put it. But as he prepares for the French Open, he yearns to copy McEnroe in one way only, by reaching and then exceeding those 42 consecutive wins.

If he succeeds in doing so, then Nadal will have had to relinquish the title of king of clay, and attention will turn to what for so long has seemed unthinkable. That one man, named neither Nadal nor Federer, might lift all four Grand Slam titles in a single calendar year.

A life in brief

Born: 22 May 1987, Belgrade, Serbia.

Education: Having played since the age of four, most of his youth was focused on junior tournaments. Aged 12, he spent three months at a tennis academy in Munich.

Family: One of three sons of Srdjan, a professional skier, and Dijana, a ski instructor. His brothers, Doroe and Marko, are both professional tennis players. His parents now own a pizzeria and pancake restaurant on a mountain in Serbia.

Career: Won his first Grand Slam title at the 2008 Australian Open. His second Grand Slam success came back in Melbourne this year as part of a run that has seen him win seven titles and go unbeaten in 37 matches. Now the world No 2 behind Rafael Nadal, he is seen as the man to beat at the French Open, which starts tomorrow.

He says: "I am very emotional on and off the court. I show my emotions."

They say: "He's playing at a really high level. We've got to accept that. When someone is better than you there is nothing you can do other than congratulate him." Rafael Nadal

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments