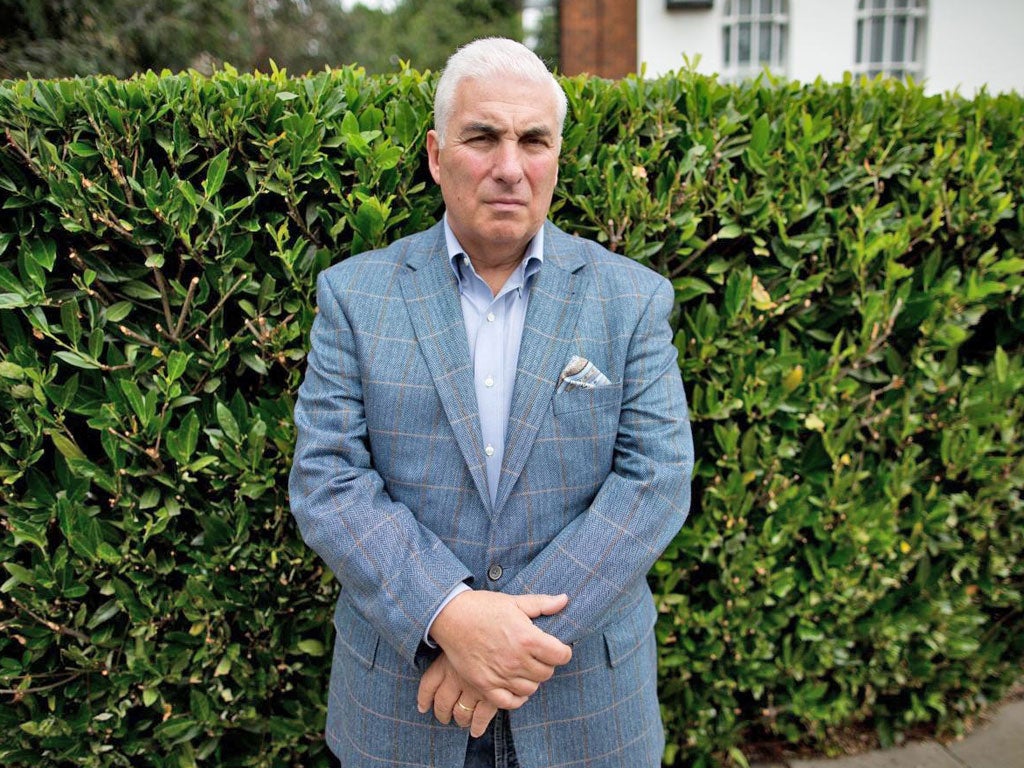

Mitch Winehouse: 'I wish it had been me that died, not Amy … You can help all the kids but it's never going to take the grief away'

Amy Winehouse's father accuses the Government of leaving addicts to die as he talks to Patrick Strudwick about the foundation set up in her name

The death of a daughter would knock the stuffing out of most fathers, but one year on Mitch Winehouse's grief has matured into anger – at the "scandalous" lack of treatment available to vulnerable addicts.

He is sitting in the modern, north London offices of the foundation which has been set up in her honour to care for drug abusers and underprivileged children. His eyes are bloodshot and glistening.

"I wish it had been me who died and not my daughter," he says flatly, glancing out of the window.

On 23 July 2011, Amy Winehouse died of alcohol poisoning after a long, horribly public struggle with drug and alcohol addiction. She was 27. Now Mitch has published an unflinchingly honest memoir telling her story from his perspective, Amy, My Daughter. His grief is raw and palpable.

"We miss Amy terribly and that's never going to…" He stops, clears his throat and starts again. "You can help all the kids all around the world but it's never going to take that [grief] away."

His accent is old-fashioned East End, his delivery direct, no-nonsense, varying between loud, tender and expansive, a clue, perhaps, to his former career as a taxi driver.

The work of the foundation is, he says, keeping him and his family going. But as Winehouse, 61, begins to discuss treatment for addicts he launches into a searing attack on the lack of state provision for drug and alcohol abusers.

"If you're an addict, you're left to die," he says. "It's an incredible indictment on our country that we leave people to their own devices. It's worse than a scandal; it's a disgrace. We've got to get people treated quicker."

Winehouse says he spent close to £1m on private treatment for his daughter – a succession of residential rehabilitation centres, hospitals and doctors – and is horrified at what he now thinks would have happened without the vast sums coming in from Amy's royalties.

"We would have tried to get her funding [for treatment], we would have been unsuccessful and she would have died a lot sooner."

And so, early intervention from NHS services is vital, he argues, and would save the country money in the long term. "But all governments think in terms of four years," he says with disdain, citing unspecified estimates that by the age of 35, the average addict will cost the taxpayer £1.5m.

"Isn't it more sensible to treat that person when they first present themselves with a problem? If we can spend £20,000 this year to put someone into residential rehabilitation, get them clean, help them find a job, then it's not going to cost us £1.5m over the next 20 years. It would also be a crime prevention programme."

According to the National Treatment Agency, in 2010-11, the NHS referred 4,232 drug addicts for residential rehabilitation. Many of the residential centres are run by charities, but it is some of the private firms that concern Winehouse. He describes them as "money-making machines" and accuses two in which his daughter stayed – without naming them – of tipping off the press about their famous patient.

He also wants to see widespread drug education programmes, so the foundation is piloting a scheme in Hertfordshire, sending recovered addicts into schools to educate children about the realities of drugs. While the foundation sets to work on this schools project, as well as setting up children's hospices and investing in rehab centres, Winehouse is learning to cope with his grief in a rather unconventional way.

"I've been to spiritualists and mediums and they've given me great proof that Amy is still there. Some of the messages we've been given have been incredible – only things I would know, nothing they could have got from the internet. I sat with a top psychic in America – I can't remember his name. The FBI uses him on cold cases to help find missing bodies. The first thing he said to me was, 'This is Amy: "Dad, there is a life after death'."

Winehouse sighs, suddenly aware of how this sounds. "I don't want people to think I'm a deluded fool," he says.

But he simply sounds heartbroken; a parent clasping whatever offers comfort. I'm reminded of something he said at the beginning of our meeting.

"When I got the news [that Amy had died] and we were flying back from New York, I thought, 'I don't think I will recover from this. I'm losing my mind.'"

Writing the book has helped him process some of his grief. The advances from the British and American publishers –"in excess of £1m" – will all go towards the foundation.

The book is littered with tales of tabloid journalists' unscrupulous behaviour towards his daughter. Was her phone hacked?

"It was," he says. "But they hacked the wrong phone – the phone at her flat in Camden Town. There was a line in there but it never worked: she forgot to pay the bill. The police contacted us and told us [about the hacking]."

However, his focus remains the work of the foundation. "It's given me a sense of purpose. The Grammy awards? Fantastic. The music? Brilliant. But this – feeding kids, helping addicts – makes me more proud. It's just a shame Amy's not here to see it."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks