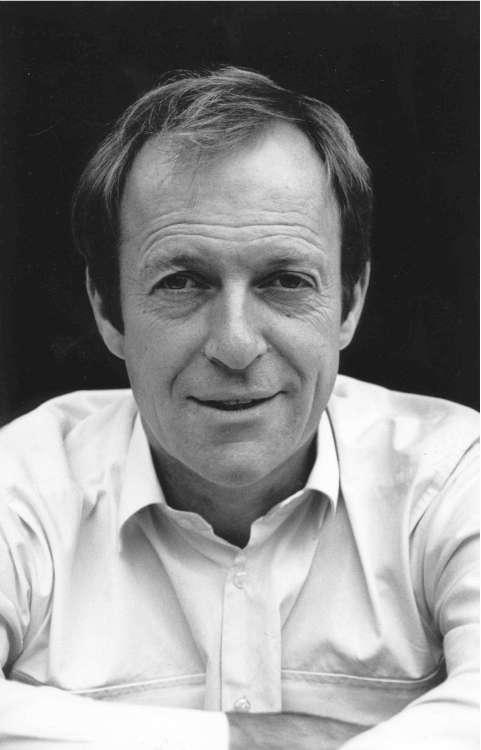

Miles Kington: The last tapes

Just before he died earlier this year, The Independent’s beloved humorist granted an extraordinary interview to his friend Tony Staveacre

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.For a man who wrote at least 800 words nearly every day of his life, Miles Kington was always reluctant to write anything about himself. He boasted that one of his hobbies was laying false trails for nosy biographers; and his only attempt at autobiography had evolved of its own accord into a marvellous fiction – the book, Someone Like Me, which was published in 2005 and caused real confusion to booksellers, who didn't know where to put it.

So it was his wife Caroline's initiative, just before last Christmas, to invite me to bring my tape recorder to their home near Bath, and persuade Miles to talk into it about the main events of his own life. He was already very ill with pancreatic cancer, and there were things he needed to do, while he still could. Creating the structure for a bona fide biography was one of them, and talking to me would be easier than typing. I'd known Miles for nearly 20 years. We worked on many radio programmes together: he – a witty and knowledgeable writer/presenter, me – a pedantic, old-school producer, who didn't share Miles's penchant for spontaneity and last-minute deadlines. It took me a while to recognise that Miles couldn't deliver, unless he was really up against it. Was this to be one of those times?

Our first session was 11 January, in the afternoon. He gave me a hug when I arrived, but I was shocked to see how frail my friend had become, and my eyes will have hinted at my dismay. Anyway, I set up my microphone and tape machine in the snug parlour of Lower Hayes (a house where Nelson once slept) and we went to work. Caroline had suggested some topics for our conversation, but she'd gone to the shops, and we'd forgotten what they were. A train buzzing along the branch line at the bottom of the garden gave an appropriate starting cue for our first session.

MK: Between the ages of about eight to 13, I was really interested in train-spotting.

We lived in a small village in North Wales, Gresford, the site of a major pit disaster in the 1930s. This was on the GWR line, and we'd get wonderful trains going through there, like the Pines Express going to Bournemouth. I didn't know where Bournemouth was, but I knew it had pines.

I did get the Ian Allan Spotter books, which listed all the known engines. You'd wait till you saw an engine then you'd underline it, then you'd got it. Lots of Manors came through, also Halls and Granges, I suppose these were great houses in the GWR area, and the owners of the railway got a fee out of the house-holders. Then there were Castles and Kings, very grand. King George V had a bell on the front; I only saw it once. I sat on Gresford station, checking them off. Seasoned train-spotters could tell the home depot of an engine from the code on its side – Old Oak Common or Swindon.

TS: These were steam trains?

MK: Yes, of course, this was the late 1940s. I loved what the engines smelled like, and how they looked, descending from the Welsh hills going at a hell of a lick, and then struggling up the other side. I enjoyed a great spectacle either way. Other lads from village used to go train-spotting with me, and they'd all started smoking! I wasn't interested in those naughty things, so I'd say, "I'm going up to the woods." I convinced them that I was interested in wild flowers, and in fact I taught myself their identities. It was train-spotting all over again! I knew the names of Jack-by-the-Hedge and Coldsfoot, which flowers before its leaves come. And I'd know the seasons, whether bluebells or snowdrops came first...

This has made me wonder: am I a train-spotter by nature? I do like having it all written down. I have to have a recipe in the kitchen, unlike my wife – just give her three peppers and a bit of stock. She says: "You don't need a recipe, just need to know the system!"

Cooking, wild flowers, trains – it's the same terrible pattern. I'd like to think I'm an improvisatory sort of guy but I'm not really. I love map reading, I like to see where we are on a map. Train-spotting all over again. Of course, Gresford station is closed down now. So much of my life was wasted there...

Miles was born in Northern Ireland, where his father – an officer in the Royal Welsh Fusiliers – was stationed during the war. Downpatrick in County Down was "20 bars, a racetrack and a lunatic asylum". After the war, his father worked in the family brewery in North Wales. Miles was sent away by train to a boarding school in Perthshire.

MK: There are only four or five famous schools in Scotland, and this was one of them: Trinity College, Glenalmond. The school was very keen on rugby and shooting (I hated both), and on the countryside: you could be turned out in the hills for eight hours with a packet of sandwiches! I quite enjoyed that part of school life.

Half the pupils were Scottish middle class, the other half were imports from Northern Ireland and England. I was once attacked by Thompson, a big guy, son of a farmer. While he was beating me up, I asked him, "Why are you attacking me?" "Because you're English!" We became great mates after that.

TS: Why were you sent to this school?

MK: Because my father had been there, and his father before him. Why do fathers do this? It's the same old story: chaps go to these schools, they hate it – and yet still they send their sons to the same place. "Oh, it's all right now." I vowed that I would never send my children to boarding school, and I've kept to that.

I was very unhappy, and would much rather have been back at home. I hated dormitory life. I had a problem with bed-wetting, which was incredibly embarrassing. Horrible memories of not being in control. You couldn't escape, because the school was so far from civilisation, miles away from Perth. I don't remember anyone ever running away.

School did at least encourage the development of Kington, the humorous writer.

MK: At 14 or 15 I knew I wanted to be funny. Richmal Crompton and SJ Perelman were my heroes. I wanted to be like them, so I started writing funny stuff. There were boys around me who were really funny – like the Cockburn brothers. Their father, Claud Cockburn, ran a scandal magazine called This Week: all his sons went to Scottish public schools. Alexander, the eldest, is now a journalist in America; his brother, Patrick, writes for The Independent. I was very much under the influence of Alex Cockburn – he was way beyond me, he'd done things, he'd been a Communist, he'd slept with a girl! He wrote very funny stuff, and he and I ran an alternative school magazine for the 1950s. It was called Quintet – a bit of a ragbag, travel, cartoons, humorous stuff. We had great fun doing it. I spent one summer looking for advertising in Perthshire. I learnt all about running a magazine.

And school also developed the musician. Miles had already had piano lessons at home and become quite a good pianist.

MK: I think my father was making up for things that he'd never done: "Miles, you will learn the piano." Hours of practice, graduating from sonatinas to sonatas, years of Clementi – I even got to like him!

Then I heard jazz! I thought "What is that?!" I haunted the local record shop in Wrexham. The first LP I bought was the Chris Barber Band – New Orleans to London. Then Red Nichols – The Roaring Twenties. I was in heaven. My gang of teenagers thought Buddy Holly was rubbish! We were listening to Sonny Rollins, although I have to confess that I never really got him.

Then I thought – maybe I could play this stuff? But it was already too late, because I'd learnt to play music as it was written down, and never been encouraged to improvise. So I realised I'd never be able to play jazz on piano. Just then, my piano teacher at Glenalmond – Noel de Jong, a lovely man – needed to recruit some trombone players for the school orchestra. So he and I both learnt to play the trombone together. And then we had a school jazz band, in which I was the only improviser, so I wrote out everybody else's solos!

I also had one glorious season in a dance band at the Wrexham Memorial Hall, playing second trombone in Glen Hanmer's 12-piece dance band. We played as much jazz as we could, although the dancers always wanted ballroom music. The cha-cha-cha was all the rage, so we had to play everything in that rhythm – Glen Miller's "In the Mood" as a cha-cha-cha! Awful. But I loved it. I was accepted as a grown-up, they told me dirty stories, and I learnt the musician's point of view, which is always a minority point of view.

After school Miles had a gap year, before he went to Oxford. This was unusual in the late Fifties, when National Service usually filled the gap between school and university. Anyway, Miles used his time off by crossing the Atlantic, and going to work as a translator in an office in New York.

MK: I took a banana boat from Wales to the Caribbean, because the plan was that I would stay with Aunt Peggy in her hotel in the Bahamas, then work my way up to New York. In New York, an exchange scholar at my school had fixed me up with a job at his uncle's legal firm in Wall Street, doing German translations for them. It was very boring. But I did hear all the great jazzers: Teagarden, Bobby Hackett, Ornette Coleman. I hung about in Greenwich Village, reading Ginsberg and Kerouac.

I was quite a pretty lad in those days, so I was quite often accosted by homosexuals! I remember a huge black man once confronting me on the sidewalk: "My master has observed you from his car... He likes English boys."

TS: I expect this experience of the world gave you a real advantage when you got to Oxford?

MK: When I got there, I felt I'd been there, done that. But Trinity College had a lot of bright guys from Sheffield that year, and they ganged up on me: "Don't keep going on about America, lad!" I felt quite lonely again.

My scholarship was to read French and German – that was all I was good at. Most of the course was a waste of time, often boring. I grew to really hate the syllabus. Strangely, we didn't learn the languages, so I never spoke French. I did get quite keen on medieval French: I found that it was the link between Latin and modern French, where they met in the middle. I found that fascinating; it got me through. I still wish they'd taught us to speak French. Indirectly that led to my "Let's Parler Franglais!" columns in Punch, which later on became part of my livelihood.

Of course, at university the learning part of your life is very different from the living part of your life. There is music, sport, activities, and the social life. The learning part you never talked about...!

When I got to Oxford, I realised I was not the best trombonist in the University, far from it. But then I heard someone say, "What we really need is a good string bass player..." So I learnt the string bass! Most bass players complain that they're the backstreet boys in the band, but I was very happy to do a behind-the-scenes job.

I came back to Lower Hayes the following week. Waiting for Miles in the sitting room, I snooped through the tapes and books that littered the floor, around the sun-bed where he was most comfortable: a biography of Miles Davis, Betjeman's 'Pictorial History of British Architecture', 'The World the Railways Made'; video-cassettes of Dylan Moran and Al Murray; LPs of Illinois Jacquet and Stan Kenton; 'Bleak House', 'Jules et Jim', 'Black Narcissus'. His faithful spaniel Berry was snoozing on the hearth. Miles was a cat man, but he and Berry had become inseparable. When Miles took up golf, Berry became his ball retriever. But he never learnt how to bring them back unchewed. We'd agreed that our next theme for discussion would be career paths and life choices. Miles's father, Bill, always regretted having made the wrong one.

MK: Dad had always wanted to live in Kenya, to be a coffee farmer. He'd spent some time out there and loved it. Loved the flora and fauna, the dogs, the black mambas. For the rest of his life, he'd get periodic bouts of malaria. But he had to come back to Wales because Uncle Evelyn needed help to run the family brewery in Wrexham. This was Border Breweries – "Order a Border" was their motto. They had 200 pubs in Wales, dad had to visit them all, and check up on them. He hated the job.

Anyway, after I'd left Oxford, Dad expected me to go into the brewery, on the wine side: "With all those modern languages, you'd be just the man." I told him I didn't want to go into the brewery? "So what will you do?" "I want to be a humorous writer!" With unaccustomed wit, he said: "So – what's the pension scheme like?" I laughed then: I'm not laughing now!

Ten years later he did tell me I'd made right choice: "You can't bear fools gladly, and – if you're a businessman – you have to."

So he became a freelance writer and married his Oxford girlfriend, Sarah (known as Sally) Paine. Terry Jones shared a room with the couple in Oxford, before they moved to London.

MK: After Oxford I was playing bass in the pit band of an Edinburgh Fringe show: the Oxford Revue of 1963. Terry Jones was in that show; we got on really well, and so we decided we'd try to write scripts together. We weren't very successful, although I seem to remember that we had a play put on radio. Terry said to me one day: "You are interested in words, I'm more interested in performing." So that was the end of our partnership. Anyway, he'd just been waiting for another friend of his to finish at Oxford, whose name was Michael Palin. I think they did quite well together.

The Kingtons lived in a first-floor flat in Notting Hill. Their daughter, Sophie, was born in 1966, and a son, Tom, followed in 1968.

MK: I was contributing to Punch, and also sending stuff off to lots of other magazines – Queen, Town. I would write to newspaper editors: "I'm the columnist that you ought to have!" But I did manage to do some well-paid pieces for serious magazines that wanted a bit of humour. In one moment of hard-headedness I recognised that a funny piece about supermarket trolleys might find a place in a grocery magazine.

We lived in the world of flower power, just off the Portobello Road. Although we were surrounded by hippies, we took no part in that alternative lifestyle. What I desperately wanted to do was to get on the staff of Punch, which was probably the most conventional thing to want to do, in the Sixties.

I used to sit on the balcony with a little table and type in the open-air on a portable typewriter, with carbon paper and Tippex. Do you remember those old typewriters had a bell that would ring when you got to the end of a line? I thought my bell was broken, because it was always ringing too early, at half-lines or quarter-lines. But then I realised that it was the hippies passing in the street below and jingling their bells! It was a historical moment. I thought: I must remember this – and I have!

TS: You then started working at Punch. What was your job?

MK: I was assistant editor, then literary editor. We only had one book page a week, but we'd get celebrities to write the reviews, which has become a common syndrome today: Terry Wogan, Sandi Toksvig, are invited to contribute because it's assumed they'll write funny stuff (which is not necessarily true).

Looking back, if you were at Punch, it was rather like public school life, we'd get up to japes. Bernard Hollowood was the editor when I joined the staff, after him they took on William Davis because the magazine was in financial trouble, and they needed someone who knew about money and journalism and Fleet Street. They thought he was the answer to their prayers. At the time, we all ganged up against Bill Davis, and gave him a really hard time. I remember him storming down the corridor complaining "everybody on this magazine is so literary – who wants literary humour" and we were all horrified. But actually I think he was right! Punch in those days was into little light pieces, "butterfly" pieces.

TS: Where did the idea for Franglais come from?

MK: I was sweet on the arts secretary Pamela – she used to go to French lessons at the City Lit. She missed her class one week, so as a joke I wrote her missing lesson, and sent it to her. Then I showed it to Alan Coren, who was then the editor, and he liked it so I did some more. Poor old Pamela was sidelined! But the column really took off, and there were several anthologies published subsequently.

The young freelance writer was also still very much involved in the world of jazz.

MK: I was actually the jazz reviewer for The Times. Was that a job? I'd sent them some pieces, saying "you should review jazz performances". No response. Then, some months later, the arts editor sent me a letter, he had come under pressure for not covering jazz, so he thought of me. Being an old Times hand, he thought we should only review concerts, and not bother with gigs in clubs like Ronnie Scott's. But I did get to cover some great concerts: Dizzy Gillespie on the same Festival Hall bill as Jimmy Smith, the organist.

In 1967 Miles dusted off his double bass, and got together with a gang of doctors, to make musical comedy.

MK: Instant Sunshine, which is possibly the worst name ever for a group, was started at St Thomas's Hospital. All hospitals have entertainment shows. They have amateur film-makers, and if you can act or sing, there are always others to get together with. Peter Christie wrote songs, David Barlow played guitar, Alan Marriott-Davis was very funny. How did I get in? They needed a bass, that was it. Also, that was the making of me as a public speaker. I had a knack for doing jokes and funny introductions to songs. Mostly I cowered behind the bass, but when we started going to the Edinburgh Festival (we went 10 or 12 times), I found myself doing jokes about life in Edinburgh, so I would do a 10-minute monologue about Edinburgh.

We made three or four LPs, we even had our own series on Radio 4 after we'd been the resident songsters on Stop the Week with Robert Robinson. We wrote new topical songs every week. We recorded our songs before the main show, but stayed around for the champagne after. We thought we were doing well, getting to meet celebrities...

And about that time, I also got my first appearance on TV: I was invited on to Late Night Line-Up on BBC 2, to talk about Jacques Loussier, who played jazzed-up Bach! William Mann, music critic of The Times, was also on: he said Loussier couldn't play Bach, I said he couldn't play jazz, and Loussier said: "Why do use these labels? It doesn't matter, it's all music – there is only good music or bad music."

I thought "What am I doing on TV, saying this guy is no good, he's sold millions of records?" Somewhere I have a photo of me with a cheroot talking to him. That was my TV career for a time, until Frank Muir came to a Punch lunch, and invited me to be on Call My Bluff. I did quite well; I was on it quite a few times.

The next turning point in Miles Kington's literary career is dated 1979, and coincided with major upheavals in Fleet Street.

MK: When The Times was up in the air, I was unsettled at Punch, so I wrote to Harold Evans, editor of The Times. I said, "You need a humorist, I am he." Harry said "Give me some time, I'll think about it." I was really determined, and I decided to write him some examples of the kind I'd like to write, and sent him a piece every day until he said yes nor no. I tried really hard, and wrote really strong pieces, topical or fantastic. My nerve didn't crack, and eventually, after 10 or 12 days, he said, "Let's give it a go." In that instance, persistence paid off. We had to decide where would it go in the paper. The only free space was at the bottom of the obituaries page, so I suggested that we call it "Over My Dead Body". No, he said, that was really tasteless. So it became "Moreover".

TS: How many years did you do that?

MK: About eight, starting in 1979. Then I transferred to The Independent in 1987, and I've been continuous with them since then.

TS: How many pieces?

MK: I suppose about 6,000 pieces for both papers – and many different! Occasionally I do use the same jokes again. And some jokes I've stolen from the French. But repeating yourself is sometimes an advantage. Readers want you to revisit themes that they've enjoyed, like Uncle Geoffrey's Country Walks, or the gathering of all the gods. I get letters saying, "when are the deities coming back?"

That conversation was recorded on 18 January 2008. We arranged a further session for the following week. But when I came back eight days later, Miles was really ill, despite his best efforts to conceal it. His wife Caroline had also been laid low with the norovirus, and her daughter Isabel had come to stay in the house with her little boy, to look after the two invalids.

I suggested that we postpone our chat, but Miles wouldn't hear of it. So we continued where we'd left off, with newspaper columns, and one of Miles's literary heroes, the American humorist, SJ Perelman.

MK: Whenever anyone asks me about writing columns, I always refer them to The Paris Review, which used to run interviews with great writers. Usually you find that writers don't like being interviewed. They don't like to give away their secrets – because, of course, they don't know what they are. Anyway, The Paris Review managed to persuade Evelyn Waugh and SJ Perelman to agree be interviewed, and their man put the same questions to each. Asked about James Joyce, Perelman said: "I choke up with respect." Waugh said: "He did write one good short story before he went mad."

The interviewer then asked Perelman: "Is there a novel you're working on?" Perelman said: "Academics with PhDs, or bespectacled chaps with domed bald heads like Rocky Ford melons are always asking me: 'When are you going to knock off this trivial stuff and do something serious?' I say to them: 'The art of the miniaturist is as important as the art of the muralist.' I'm a miniaturist, I do little pieces, and if I can achieve perfection in my miniatures, I'm as happy as I would be with a fresco 12-feet long."

Although I find to my horror now that Perelman is not as funny as I thought he was, his attitude is right, and I share his ideals. Every day I sit down and say I'm going to write the funniest piece in the world. But I never do.

Where do the ideas come from? I like thinking of something odd: "Wouldn't it have been funny if...?" or "What if someone had said...?" My pile of discarded ideas is much larger than the pile of used ideas. The GP I go to is a doctor called Johnson, Dr Johnson. It occurred to me that it would be funny doing an interview with a GP in the style of the famous Dr Johnson. Maybe that's a flimsy starting-point? Halfway through you're never sure if it's working or not. If you see the shape in advance you're going to go wrong. I like to start with the first paragraph and see where it takes you. The funniest bits are often not where you started. Often the joke you started with gets dropped before the end.

TS: Do people sometimes ask you, as they used to ask Perelman: "When are you going to do something serious?"

MK: Yes, they sometimes think of me when they want travel pieces. I did four pieces for The Times about travel destinations that used to be fashionable: like Biarritz, or Le Touquet – what are they like, have they burnt down? But after doing a couple, I thought they were all looking the same, so I counter-suggested with a better idea. I said I could write about places in Britain, but in the grand old style of travelling, as if they were Katmandu or Nepal: "Up the North Face of the Wrekin" or "Journey to the Unknown Interior of Jersey". That worked quite well. And I have done features on people. But that's going towards real journalism and I'm not a real journalist, I don't go off and report things.

Whenever I haven't got much time, I think about something that has happened to me that I feel strongly about. I was sent out to Burma to film there, and I felt strongly about the awful regime, and was moved to wrath. But those pieces are very hard to write because you find yourself having to be icy calm and yet very angry and yet full of facts and know what you're talking about – it's a hard old tightrope not to fall off.

TS: But you have presented radio programmes on serious subjects?

MK: Yes, I can do that journalistic trick of soaking up a subject over a few days, to pass myself off as an expert.

TS: Your TV and radio commissions have mostly come from producers wanting you to take a "Milesian" look at things, from a quirky stance? Are you happy with that?

MK: I wish they'd do it more often! Some of those things came out of the blue.

The reason I got to go up the Andes and make the film about Peru was that I had vaguely known the executive producer of the series at Oxford, although I hadn't seen him for many years. He was looking for the next new TV presenter. Like Michael Wood doing history. "We need to try a new face", that's what They are telling us. Who are They? I was a new face for a while.

That was the first of the Great Railway Journeys series. It was the tallest, highest railway in the world: "Three Miles High" (that was our title) from Lima at sea-level over the top of the Andes to Huancavelica, to get to the silver mines. The railway is still in operation at 19,000 feet (Everest is only 29,000). There was a military coup in Bolivia while we were filming, so our plans fell to pieces. We only got back down by hitching a lift in a lorry. We were holed up in a hotel in La Paz opposite the university: there were tanks in the street, shelling the university.

TS: So did you foresee new opportunities coming out of this experience? Did you see yourself becoming multi-media?

MK: I didn't see myself as anything at all! I never did. It was a bit like being sent way to school all those years before. I didn't ask why, just went away and did it. It was a job, it seemed a good idea at the time. Also: my private life was falling to bits at that time, because my first wife left me the day after I came back from Peru: "Oh and another thing – I'm going to go off and live with Paul." "WHAT?" Which actually worked out very well in the end, but it wasn't something I was looking forward to hearing. I'm not very good at handling that sort of thing. Because I tend to be rather conservative and stick with the arrangements I've got.

TS: How old were your children at this time?

MK: 12 and 14. It's not a good age, but it's never a good age for splitting up from your children.

As you can see, my life has not been planned at all. I'm not the sort of person that has a life plan and says, "at that time I'll be doing this, by then I'll be writing the novel..." I did have vague ideas, when Caroline was encouraging me to write plays, that one day I'd write a super comedy, a smash hit which would see me through my penurious middle-age, but it's never happened. I seem to have been facing the wrong way quite often during my life!

TS: And have their been moments of the "fork in the road", big choices that you've had to make?

MK: Oh yes, usually to do with TV, when people have seen what I've done and said: "He's got a nice touch there, he's done that job well, what else can we get him to do?" I invariably say "No"! After Peru, I made a film about the Old Burma Road, the route into China built by Chiang Kai-Shek. Another producer saw the rough-cut and said: "I like how you've done that. We have a scheme to make a film of Around the World in 80 Days – would you like to be the presenter?" I'd just done two or three months of television, my new wife was pregnant with our child, so I said "no" and they gave it to Michael Palin. Sometimes I meet Palin and he says, "I bet you wish you'd done it!" No, I don't – but I do wish I'd had the money!

TS: Dear man, I'm going to stop there, we've recorded nearly 70 minutes and Madame said I shouldn't stay too long. Just tell me so that I know where we're to pick up next time: when did you come to Bath?

MK: 1987. Everything fell apart in 1981, and came together again in 1987. Because that was the year I got married again. Then we had one more child, he's now 20, and I'm speaking to you in 2008. In fact Adam was born in 1987, the same year Caroline and I got married, very nearly the same day we got married!

TS: And you're a grandfather now?

MK: Yes, my daughter has two girls aged 10 and eight, I think. (Oh God, she'll hear me!) I'm not a very active grandfather, because they're in Norfolk, so we're not really available for baby-sitting.

I did suggest to my wife when she was pregnant with Adam, children seem to get on really well with their grandparents, often much better than they do with their parents: so why don't we tell our son that his parents were killed in a car crash, and that we are his grandparents?! She didn't like the idea, but I still think there's some juice in it.

My grandchildren are wary of me: they think I'm an odd character. Perhaps I am.

And that's where the last tape ends. It was Saturday 27 January, about tea-time. Miles was clearly exhausted: in fact, he was asleep before I left the house. On the Sunday, unusually for him, he was late getting his column to 'The Independent' for Monday's edition. He spoke to his editor, said he was really sorry, he thought he had a touch of the virus! It was another struggle, to get the next day's article finished, but Miles told his wife that he didn't want to let them down. The following day, Caroline rang the newspaper and told them that Miles was now too sick to write, and that he'd better have the rest of the week off.

That was the first day in living memory on which Miles Kington failed to file his newspaper column, and that was also the day that he died. True to form, this clear-sighted and courageous man had already provided a typically Milesian explanation for this unusual lapse.

TS: What about you and DEADLINES?

MK: Ahhhh! Where would we be without deadlines? Well, it didn't take me long to notice, in the hack racket, that without deadlines, a journalist would never get anything done at all. And when you say to a man "give me a piece for Friday lunchtime" you know he'll start on Friday elevenses.

The editor will ring me up: "Miles, how's that piece coming along?" – and you can't remember what he's talking about!

"Which piece is that?"

"The American Civil War."

"Oh right; and what approach did we say we'd use?" (You're getting him to tell you what you've forgotten!)

"Oh yes, as an Agatha Christie mystery."

"By this Friday?"

"A bit sticky. Monday?"

"That would be fine."

You know then that he didn't want it by Friday! He was lying, and you were lying!

I'm lucky, I've got a daily deadline. It's an open-ended deadline, so I'm living right on the edge. Fellow journalists know that if I don't get it in by four o'clock, I've nothing in reserve. I never have one "in case". In case of what. In case I die, to tide me over one more day?

I did once do a stock piece, because I'm a good boy, and they asked me for one. But they used it the very next day! I said, sod this, I'm never doing that again! They know now that if I don't do a piece, there must be some very good reason for me not doing it!

Tony Staveacre presents extracts from 'Kington's Last Tapes' on BBC Radio 4, tonight, 8pm. Miles Kington Remembered continues in 'The Independent' on Mondays

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments