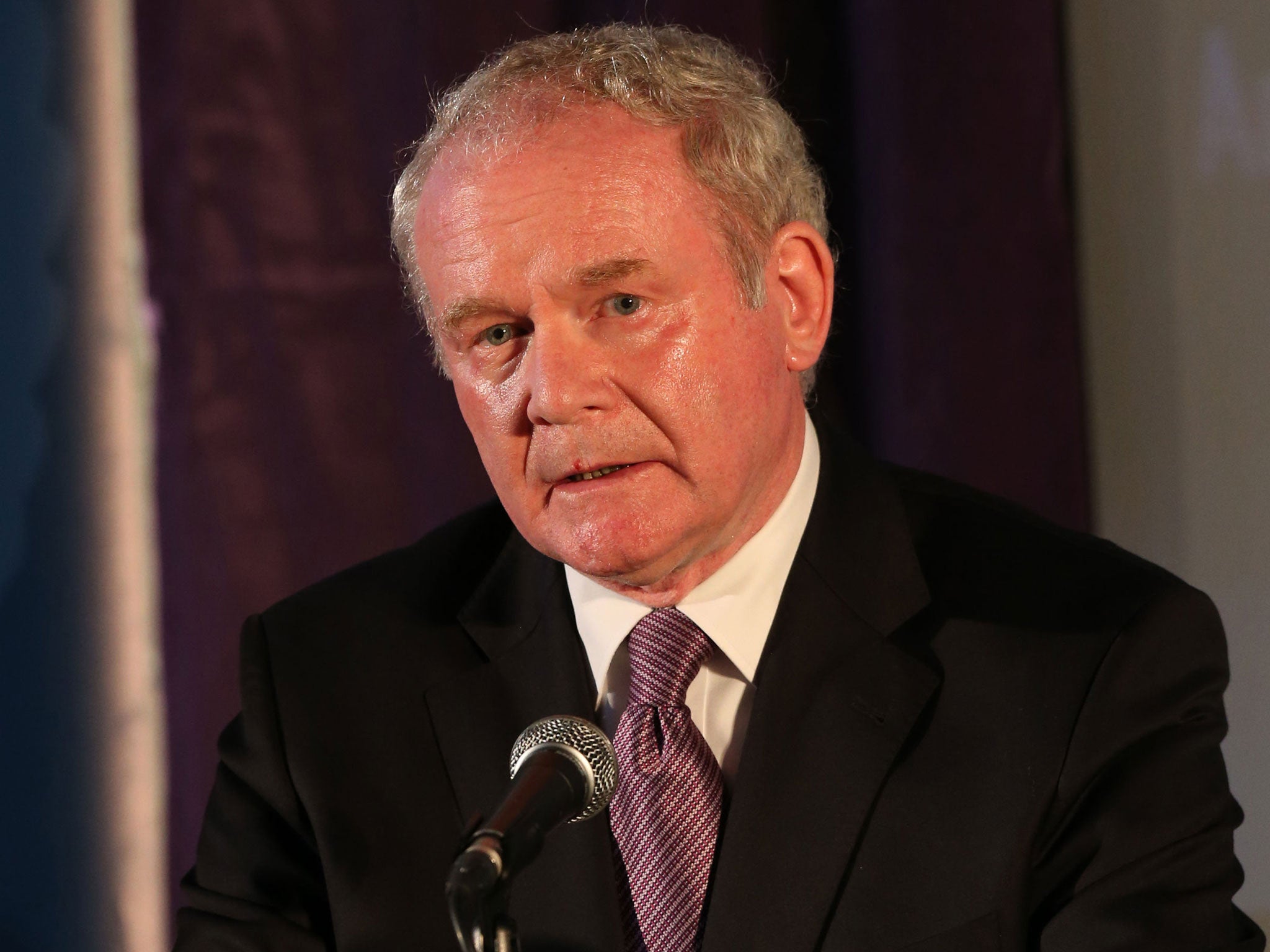

Martin McGuinness: ‘I think there are people aggravated by me and Sinn Fein being in power’

Martin McGuinness tells David McKittrick how Stormont has ‘failed’ on the peace process – and how it can be fixed

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.For decades Martin McGuinness’s life was devoted to insurgency and “armed struggle”. Having made the switch from war-war to jaw-jaw, Northern Ireland’s Deputy First Minister is now focused on relationships and politics.

“The lesson from the conflict here is the same for everywhere else,” he says, as he surveys the situation in the Middle East. “There are no military solutions – dialogue and diplomacy are the only guarantee of lasting peace.”

The threat to that peace process feels stronger now than it has done for years, however. It has been a bad year for the province, with plenty of political sniping that has been matched on the streets, with hundreds of police hurt in clashes with Protestants.

No stone was left unturned in attempts to bring the warring parties together for the Good Friday Agreement – but rioting has broken out so often in recent months, with barrages of missiles thrown at police, that in some loyalist areas it sometimes seems no stone has been left unthrown.

The state of play was summed up a few days ago by the former US Senator George Mitchell, who helped put the peace process together. “They are at peace now,” he said, “but it’s fragile.” Meanwhile, the Prime Minister, David Cameron, said on Friday that, while he would not describe things as a crisis, “there are a lot of difficulties to overcome”.

At this time of great tension, Mr McGuinness’s trip to Warrington last week – to speak at the invitation of Colin and Wendy Parry, whose little boy Tim was killed by an IRA bomb 20 years ago – was a reminder of the reconciliation and that can come with negotiation.

“I thought it was important to go, to acknowledge the hurt and the pain. People who came up to me afterwards were very warm,” he says. Tim’s parents, whom Mr McGuinness describes as “very exceptional people who have made an enormous contribution to peace”, have set an example that many can only hope will serve as an inspiration as Northern Ireland once again has to look beyond its borders for help to solve its problems.

The sense that things need fixing has resulted in the arrival in Belfast of Richard Haass, an American diplomatic heavyweight given the formidable task of making progress on marching, flag-flying and dealing with the past.

“I would have considerable confidence that Richard Haass can move things forward,” McGuinness tells The Independent. “He knows this place inside out. I hope we can get a resolution on flags and parades, because that’s where the violence has emanated from.”

But is calling in an outsider not a sign of failure on the part of the administration? “I’ve accepted publicly there has been a failure, particularly on the issue of the past,” he concedes. “There’s a collective failure. The past is going to be very difficult because there are so many narratives out there, but at least this is an attempt to begin the process of tackling that.”

For him, and everyone else, the immediate priority is to address marching and flag-flying, the toxic topics which spark disorder. “Parades and flags are obviously issues that have jumped up to bite us. I have made absolutely clear to Richard Haass my view that the street disorder is emanating from the Orange Order and the UVF.”

The loyalist groups, headed by the Orange Order, say they are marching to uphold their rights and defend themselves against republican attacks on their culture. They want freedom to parade, even in contested areas, and they want the Union Flag flying every day at Belfast city hall.

The general belief is that the most active loyalist paramilitary group, the Ulster Volunteer Force, orchestrates the rioting which has injured police, damaged commercial life, and heightened tensions. Some of its leading members have been accused not just of rioting but of involvement in drugs, extortion and rape.

Last year’s reduction in displays of the Union Flag came about, Mr McGuinness says, following a democratic council vote. Other decisions go against Sinn Fein “but we accept that we’re not going to get our own way, and we abide by them – nobody has resorted to conflict on the street.”

“We saw them bringing people on to the streets – which is fair enough, I don’t have any difficulty in people peacefully protesting. But there was a clear agenda to use that for the purposes of violently opposing that decision.”

He detects a deeper motive for the disruption. “Within loyalism and the UVF there are clearly people who are not just aggravated by the issue around flags or parades,” he insists. “They’re aggravated by me and Sinn Fein being in government. They’re opposed to the political institutions – there’s an inability of a minority within loyalism to accept the concept of equality.”

McGuinness is critical of unionist parties, principally the First Minister Peter Robinson’s Democratic Unionists and the smaller Ulster Unionist Party. These parties are being confronted by extreme elements, he says, “and now the question comes down to people’s ability to confront this negative agenda. In my opinion there has been a total failure to confront the activities of these people publicly. I think that’s a big mistake.”

He contrasts his own stance against the violent republican extremists who have killed soldiers and police: he has denounces them as “traitors”.

“Nobody has any doubt where I stand in relation to those who believe it’s a good idea to kill soldiers and police and prison officers.”

His message to political unionism is to challenge loyalist rioters: “What’s important is that, when you’re tested, you stand firm against the violent activities of those who would try to plunge our people back into the misery of the past.”

But while he aims this message towards unionist politicians in general, he declines to direct any personal criticism towards Mr Robinson. This is partly because the two figures are off to the US together to seek investment, but mostly it is because this is the most important relationship in the politics of Belfast.

One undisputably bad moment for their two parties came last month, however, with a Sinn Fein parade through the village of Castlederg to mark the 40th anniversary of the deaths of two IRA members killed by their own bomb there. The parade had a distinctly militarist character, featuring the depiction of an Armalite rifle and men in paramilitary gear. There were protests over the event, with complaints it had “retraumatised” a village where almost 30 people died at the hands of the IRA.

How did McGuinness react to the criticisms? “Some claimed it was a celebration but it was not; it was a commemoration,” he insists, before adding: “But in terms of the parade there is a lot of reflection to be done in regard to how these situations are conducted... The last thing I want to see is any commemoration used in a way which causes offence to anyone.”

He concludes: “I am absolutely passionate about the peace process and passionate that we will under no circumstances see the situation slip back to where it was before. And I’m still passionate about working with unionist leaders.”

Troubled Waters: McGuinness’ career

Born in 1950, Martin McGuinness has been a republican activist since the Troubles erupted in Northern Ireland in 1969. He admitted being second-in-command of the IRA in Derry on the day of the Bloody Sunday killings by British forces in 1972.

He served two prison sentences for IRA membership but maintains he left the organisation in 1974. In 2007, after years of negotiation, he and the loyalist leader Ian Paisley became joint heads of a new power-sharing government in Belfast.

The two long-time enemies formed a relationship so close that they became known as “the Chuckle Brothers”. In 2011, Mr McGuinness contested the presidential election in the Irish Republic – coming third.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments