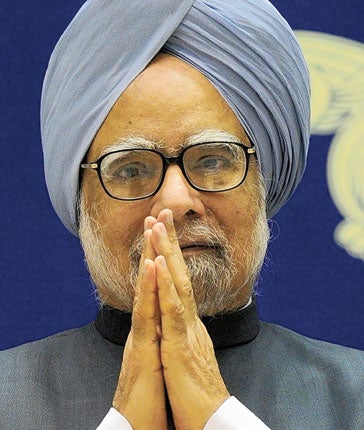

Manmohan Singh: The best man for an impossible job

One of the world's most revered leaders, he has transformed a nation of 1.2bn people. But can he save the Commonweath Games?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It's been a paradoxical week for the leader of the world's biggest democracy.

On Thursday, representatives of Dr Manmohan Singh were in New York to receive on his behalf an award for World Statesman of the Year – testimony to his continuing transformation of a nation of 1.2bn people. But as this was happening, chaos was gripping preparations for the Commonweath Games, due to start in Delhi at the end of next week, and Dr Singh's Olympian calm was being sorely tested.

For now, the crisis seems to have passed, thanks in large part to the prime minister's intervention at an emergency meeting with officials and ministers, but at the same it has to be asked why he did not realise that this showcase event was running into trouble long before a pedestrian bridge collapsed at the main stadium and the athletes' village was found to be in no fit state to host competitors.

Running India has never exactly been a piece of cake, still less so for a career economist aged 79 with a history of heart problems. But were the Commonwealth Games really so far down his agenda, so far beyond his purview, that it was only on Thursday, 10 days before they were due to start, that he noticed something was wrong?

Dr Manmohan Singh has been close to the centre of power in Delhi for nearly 40 years, since his appointment as economic adviser to the Ministry of Foreign Trade back in 1971. He knows how hard it is to get anything done in this country, how every petty boss is king in his own backyard, how the old ills of sluggishness and corruption come back like a bad vindaloo whenever they get the chance.

He has also spent long enough abroad – eight years, divided between Oxford and Cambridge – to know how much these Games matter to India's stature in the world, even if the Indian on the Delhi street doesn't give a damn about them. And they are not being staged in some remote corner of the country from which news is hard to obtain: the Nehru Stadium is only a 15-minute drive from his office. When work on the infrastructure had still not started four years after Delhi was awarded the Games, didn't it occur to the Prime Minister to bang heads together while there was still time?

Manmohan Singh is by some measures one of the most successful Indian prime ministers ever: he has won two successive elections, enjoys great personal esteem and popularity, and has succeeded in dismantling much of the so-called Licence Raj which shut India away from the world's markets, in the process giving India a shot of the economic dynamism that has coursed through the rest of Asia's veins since the rise of Japan in the 1950s. Some commentators lament that India has yet to get double-digit growth on the China model; the rest of us would say that 9.4 per cent – the IMF's prediction for 2010 – looks pretty good in the circumstances.

So how could this star performer fail to notice the shambles taking shape on his doorstep, guaranteeing India a rerun of the all the ugly old stereotypes – dirty, incompetent, complacent, arrogant, self-absorbed, above all corrupt – which he has worked hard to consign to the rubbish bin?

Part of the reason, which the rest of the world finds hard to fathom, is that if India is hopeless at doing things according to a tidy schedule, it is incredibly good at doing things in a hurry. This is a function of labour being both plentiful and risibly cheap – an aspect of the bad old India which is still a fact of life. Leave everything to the last minute, then chuck 1,500 cleaners at it: a classic Indian solution. The result will be almost OK, especially as it has to hold together for only a fortnight.

But the other reason has to do with the way in which Indian power and its symbols have changed. When India hosted the Asian Games in 1982, prime minister Indira Gandhi took control personally, ensuring by threats and tantrums that the event went smoothly. But that dictatorial model, which had earlier led her to declare an emergency, closing down the free press and locking up the opposition, and later to order an assault on the Sikhs' holiest temple, went out of style with her assassination.

Dr Singh failed to seize the Commonwealth Games by the scruff of the neck partly because that's not his style, but also because that is not how Indian prime ministers perform any more. It is not within their capacity.

Very different in particulars, there are haunting similarities between Dr Singh and his predecessor, Atal Behari Vajpayee. The premier of the first-ever government headed by the Hindu nationalist BJP, Vajpayee was sweet-natured, eloquent, poetical and vague. His gentleness and niceness were in proportion to the chauvinism and fanaticism of his party colleagues. Not without reason, he was known as the Mask.

The brilliant economist who became an "accidental politician"; the man who knew how to turn India's ignition while continuing to drive a Maruti 800, the humblest car in the market; "a man of uncommon decency and grace", as he was described at the World Statesman Award ceremony this week, Manmohan Singh has a similar function. But it is not the atavistic fury of the nationalists that he masks.

Dr Singh was appointed India's finance minister during an economic crisis in 1991, apparently at the insistence of the IMF. And although he has been in government for 11 years since, he never gives the impression of being fully in control. He was doing the bidding of big business, of the Gandhis, the markets, the Americans.

Like Vajpayee, Dr Singh offers a flattering mirror to Delhi's old ruling class, now on the verge of extinction, with his frugality, modesty, sensitivity and honesty – but the forces he has unleashed in his country are anything but modest and sensitive. The technician, the Gandhi family's discreet major-domo, he set about doing what needed to be done to usher India belatedly into the globalised world. But because India remains a grotesquely unequal and unjust society, the rapacity of the liberated capitalist class has brought misery to millions of the Indian poor who found themselves in its path.

Speaking from Red Fort on the anniversary of Independence Day last month, Singh said, "The hard work of our workers, our artisans, our farmers has brought our country to where it stands today ... We are building a new India...in which all citizens would be able to live a life of honour and dignity."

The rhetoric was boilerplate, but as the shame of the Games sank in it became glaringly obvious that the "Shining India" that Dr Singh's reforms were supposed to deliver, while improving the lot of many in the middle class, has done nothing to transform the lives of the majority of the poor.

Dr Singh has never doubted that his days in power were numbered; back in July he said, "When Congress makes the judgment, I will be very happy to make [way] for anybody chosen by the party." But as he prepares to step aside, he must feel twinges of regret about the chasm that has opened up between his fine words and India's stubborn reality.

A life in brief

Born: 26 September 1932 in Gah, Pakistan.

Education: Hindu College, Amritsar; Punjab University, Chandigarh; St John's College, Cambridge; Nuffield College, Oxford (DPhil).

Family: Married Gursharan Kaur in 1958, three daughters.

Career: Taught at University of Delhi until spotted by finance minister Lalit Narayan Mishra and appointed adviser to Foreign Trade Ministry. Finance minister from 1991 to 1996. Became Prime Minister in 2004 when Sonia Gandhi declined the job. Member of Raj Sabha (upper house) for Assam. Congress coalition led by Singh re-elected with a majority in 2009.

He says: "We are building a new India ... in which the basic rights of every citizen would be protected."

They say: "Cast as Sonia Gandhi's tentative, mild-mannered underling, he has stacked his cabinet with people committed to the corporate takeover of everything." Novelist Arundhati Roy

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments