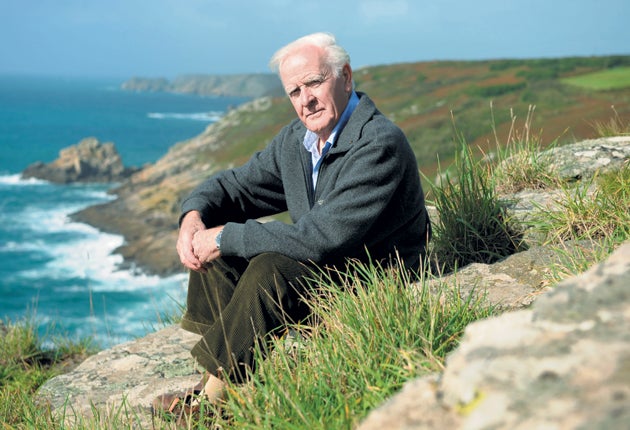

John le Carré: The spy master

An acclaimed big-screen adaptation of his best-known work is bringing Britain's eminence grise of espionage fiction a new generation of admirers.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When Yevgeny Primakov, a former KGB chieftain who led the post-Soviet foreign intelligence service, became Russia's foreign minister in the mid-1990s, he dined in London with John le Carré. "So who do you identify with in my work?" the novelist and former spook asked his fellow-survivor of the Cold War shadow-world. "Smiley, of course!" Primakov replied.

From the time of his first proper espionage novel in 1963, The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, the author born as David John Cornwell began to build a twilit house of mirrors. Inside his fiction, doubles, distortions and delusions trapped apparent enemies into a mutually dependent system of organised duplicity. It binds its members absolutely, determining their life or death, while leaving outsiders truly out in the cold. Subject to its own laws and myths, arranged according to a logic and design that turns its back on civilian reality, the intelligence netherworld that Le Carré fashioned has the quality of all great literary myths.

As much as in Tolkien, Wodehouse, Chandler or even Jane Austen, this closed world is a whole world. Its claims to documentary authenticity, however strong, hardly matter any more. Via the British "Circus" and its Soviet counterpart, Le Carré created a laboratory of human nature; a test-track where the innate fractures of the heart and mind could be driven to destruction.

That is why Le Carré has survived, and thrived, two decades after the fall of the Warsaw Pact. Thomas Alfredson's film of his 1974 novel Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy opened this week to near-ecstatic reviews – not least from Le Carré himself. It will play to many viewers who were not even alive when the Berlin Wall fell and the division of Europe – the original sin that lies behind Le Carré's multi-volume epic – slowly began to heal.

The success of a film which on every level respects its literary original hints that Le Carré's long-term prospects now look rosy again. That has not always been a cert. After the Cold War ended, critics and readers wondered where the genre of the espionage thriller – with Le Carré as its peerless practitioner – would turn next. He seemed to share those fears of redundancy. "Smiley is above all a European," he has said. After the postwar wounds of Europe appeared to close, Le Carré determined to take a global view of power, secrecy and resistance.

The 1990s and 2000s saw him take on fresh targets and relocate to more distant scenes: Latin American drug cartels in The Night Manager; Big Pharma's machinations in east Africa for The Constant Gardener, Central American imbroglios for The Tailor of Panama, western meddling in Congo, and its unreported slaughters, in The Mission Song. Yet his adjustment to a multi-polar geopolitics, with corporate malpractice as much a threat as state intrigue, sometimes felt uncomfortable, however righteous – and increasingly vocal – his anger against the skulduggery practised by bankers rather than spies.

Inevitably, perhaps, he has shown signs of nostalgia for the tawdry and compromised domain where Smiley and Karla ruled. In his latest, 21st novel, Our Kind of Traitor, the scornful satire of City of London money-laundering sounds laboured: Le Carré has stood in the front row of the bankers' critics and has claimed that Russian cash from criminal sources helped the City weather the storm of 2008. Yet the latest novel really catches fire when he return to the worn-out veterans of the "Service" in London, as bruised and bitchy as ever, or dramatises the tough Soviet background of a – rather sympathetic – kingpin of the Russian mafias.

Le Carré re-imagines the intelligence underworld; he does not report it. Yet, of course, his own background and experience shaped the contours of this unique literary landscape. Famously, he learnt about subterfuge, deception and betrayal not as a spy but as a child. His father Ronnie was a con-man, in and out of jail and the bankruptcy courts, as familiar with Wormwood Scrubs as the Savoy Grill. Le Carré's mother left when he was five. His half-siblings include the actress Charlotte Cornwell and Rupert Cornwell of The Independent.

The family fortunes soared and dived. "When there was Bentley in the front garden, we were up," Le Carré said during a revealing autobiographical talk at the Oxford Literary Festival last year: "And when it disappeared we were down and – quite possibly – out." Ronnie, who has never ceased to "fascinate and enchant" his son, stands near the centre of A Perfect Spy, the 1986 novel that for many admirers still counts as his most accomplished single novel.

During the Second World War, the young Le Carré (born in 1931) found himself "squeezing black market figs into laxative tablets" in Aberdeen at Ronnie's behest. From judges to tarts, jockeys to MPs, his errant father's own circus of hangers-on (in the good times) still, he says, inspire him whenever he needs a fruity "walk-on part".

In 1987, in Corfu, he met one of his father's old confrères. "We was all bent," the veteran fondly recalled. "But your dad was very bent indeed." Le Carré sums up the legacy of this shape-shifting patriarch of dreams and lies. "In Ronnie's bookless households, you survived or failed by your wits alone. So in a sense, I had done my spy's training in advance."

He entered the state-sponsored shadows via a roundabout route. As a student in Bern he had fallen in love with German language and literature – a passion requited last month when he received the Goethe Medal in Weimar. He studied German at Lincoln College, Oxford. There, the historian and later Rector, Vivian HH Green, provided the most likely model for George Smiley (and not, as often assumed, the former MI6 chief Sir Maurice Oldfield).

The young David Cornwell taught languages at Eton for a while. Was he, he wonders, trying to compensate for the insecurities and humiliations of his childhood? Then, in 1958, he joined MI5. The security service he entered was unfit for purpose, in his view, a broken-down "paradigm of post-war, post-imperial Britain at its lowest ebb". After three years, he transferred to the more glamorous but leak-prone secret intelligence service, MI6. He worked in Bonn, that small town in Germany, supposedly as Second Secretary at the British embassy.

In 1961, the erection of the Berlin Wall drove the young agent to fury and frustration. His response (after two earlier, more routine thrillers) took the form of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold. In 1964, by which point the defection of Kim Philby had severely compromised many agents' cover, he left the Service to write full-time. Married to his second wife since 1972, he has for four decades lived near Land's End in Cornwall, where he owns a stretch of cliff. His son, who writes as Nick Harkaway, will publish a second novel in 2012.

As Le Carré reports, his years in the underworld had a curious coda. Much later, the former MI5 head Sir Roger Hollis used to come to visit him at home in Somerset, apparently seeking refuge from some unspecified threat. It turned out that Hollis was under investigation as a suspected Soviet agent. He was not, so Le Carré believes and as Chris Andrew's authorised history of MI5 seems to confirm. "The cock-ups on his watch were just cock-ups".

Those "cock-ups", the offspring of human frailty, self-doubt and self-deception, thread through Le Carré's narrative of the Cold War as a chapter of accidents as much as a battle of ideologies. Smiley, memorably incarnated first by Alec Guinness in the 1979 BBC series and now by Gary Oldman, emerges as a flawed philosopher-priest who merely aspires to limit the harm and pain that human weakness spreads. The betrayals he clears up all stem from self-betrayal. And the Iron Curtain, the Berlin Wall – or whichever symbol of division the theatre of politics currently prefers – will always run right down the middle of the human soul.

A life in brief

Born: David John Cornwell, 19 October 1931, Poole, Dorset.

Family: Married Alison Sharp in 1954; three sons. Divorced 1971. Married Valerie Eustace; one son.

Education: Attended Sherborne school, then University of Bern. Later went to Oxford.

Career: Joined the British Intelligence Corp in 1950, then worked for MI5. Began writing in the 1960s as John le Carré.

He says: "A spy, like a writer, lives outside the mainstream population."

They say: "He is charming, entertaining, and very bright," author Robert Harris.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments