How does Tom Wilkinson - star of The Patriot, Valkyrie and Belle - maintain a low profile?

In a movie universe dominated by ageless action heroes and charmless juvenile leads, Wilkinson is an authentic grown-up, says John Walsh

.jpg)

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

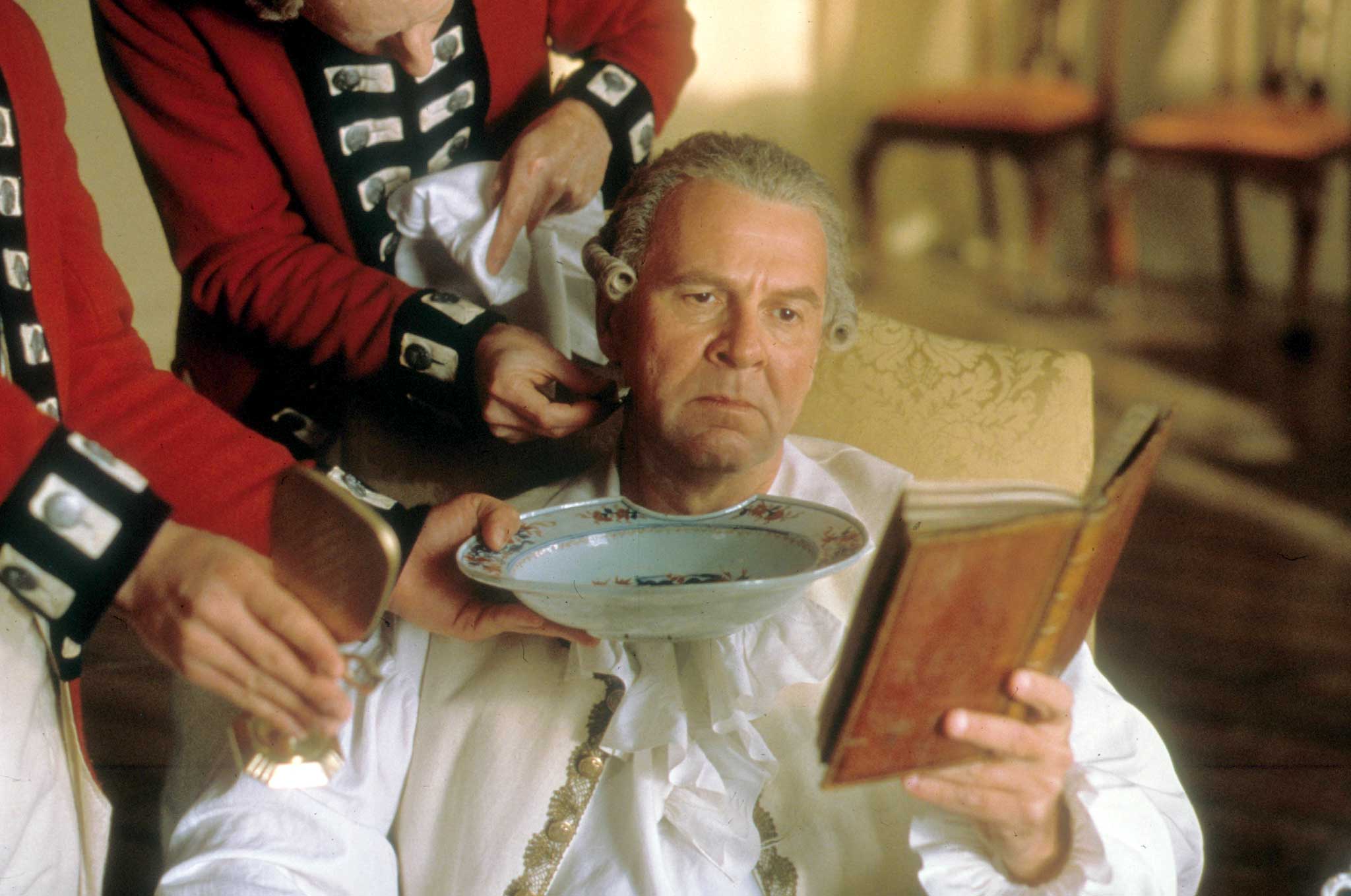

Your support makes all the difference.Few actors were put on this earth to stand, six feet tall, in a periwig, a white stock, a long and straining blue satin waistcoat and a belligerent expression, and say the words "Do you have in mind my position?" convincingly, but Tom Wilkinson is one of them.

For casting directors, he is the go-to guy for gravitas, hard-won wisdom, battered decency. Almost any lines of dialogue that issue from his thin lips carry a freight of moral seriousness. In a movie universe dominated by ageless action heroes and charmless juvenile leads, he is an authentic grown-up. He's never really seemed young. He arrived on the big screen in the mid-Nineties already middle-aged, and has remained that way ever since. His sharply appraising eyes, set in that strikingly knobbly face, can express utter contempt, shrewd intelligence and huge tenderness.

Although not everyone thinks so. "I had a Bulgarian taxi driver on the way here," says Wilkinson, plonking himself down on the sofa at a photographic studio in Soho. "He said, 'I seen you on TV haven't I? You have very... annoying face'." Wilkinson raises both eyebrows in resignation. "Perhaps he meant 'memorable'." You get the impression that Wilkinson would rather not be memorable. Before our meeting he stipulated that this article shouldn't be the magazine's cover story. Why? "Oh, it's just not my style," he said. "I like to go to Waitrose and not be recognised. Being on the cover – it's not really me."

He's good at power. He has played veteran US politicians (Benjamin Franklin, Joe Kennedy, Lyndon B Johnson) and historic English milords (Lord Queensbury, Lord Cornwallis, Lord Mansfield) but he can do a murderous gangland boss in a Guy Ritchie film and put the frighteners on villains and audiences alike. In the past decade, he's turned up all over the place, from Batman Begins to The Lone Ranger, from Valkyrie to The Grand Budapest Hotel.

Movie audiences can catch the shy-but-ubiquitous Wilkinson this month in full grown-up mode in the movie Belle, an unusual hybrid of period-drama-romance-meets-slavery-flick, set in 18th-century London. It's the story of Dido Belle Lindsay, a mixed-race 'mulatto' girl (played by Gugu Mbatha-Raw) fathered by a young aristocrat and a slave woman, and accepted into the household at the famous stately home Kenwood by her father's uncle, Lord Mansfield, who happens to be Lord Chief Justice of England. Now an heiress – the only black heiress in London high society – she encounters snide remarks, racist sniggers and outright hostility from the family's posh acquaintances, and protestations of love from a young lawyer campaigning to force English slave owners to relinquish their grisly trade.

Playing Lord Mansfield, both the girl's adoptive patron, and the judge in the slavery trial, Wilkinson is at the centre of the action. Asked why he wanted the part, he's all self-deprecation. "I read the script and thought, this is good, not least because it's set half a mile from my house. But I really was taken by the story. It's not about slavery – slavery is in the background and gradually comes to the foreground. The story is about this girl being introduced into this house, and growing into intellectual and emotional maturity. It does what art should do, it tells you how society works. It's accurate and truthful, especially about the sexual politics of that society, with the suitors sniffing around the money."

Did he think Lord Mansfield was unusual in his attitude to Belle? Wilkinson frowns. "There are rules in the family where they say to Belle, 'You can eat with us – but if we have guests, you can't eat with us'. I think they were right not to make Mansfield out to be a wonderful, I'm-not-a-racist-come-and-join-the-family kind of guy. It's important to have those little checks and balances. He's shocked when he's first introduced to her – you get a sense of him saying, 'But she's black, you can't leave this girl here'. He's a nice guy, but a stickler about her not marrying a young lawyer. In those days, if you married a rich woman, her money immediately became yours. So Mansfield and his wife look at her potential relationship with a vicar's son as catastrophic."

The climax of the movie sees Lord Mansfield making a moving speech about the Zong massacre, when 142 slaves were flung over the side of a slave ship so that their owners could claim insurance, as if they were mere cargo. It was a key moment in the history of the English slave trade, and the judge was an eloquent voice for abolition – but the film implies that his views become liberalised as a result of having the gorgeous Belle under his roof. Is it OK for movies to mess about with historical facts?

"Yes I think it's OK," he says. "Shakespeare buggered around with the truth all the time. And a film is not a documentary." He frowns again. "And truth is such a difficult thing to pin down. I was doing jury duty four or five years ago. The central element of one case was the truth of what had happened in a small room. There had been seven people sitting in the room – and the witnesses couldn't agree about who'd been sitting there. So a writer, 300 years later, can certainly fool around with stuff. Maybe you can bugger around with something that happened in the 18th century, but not the 20th century."

Wilkinson was in The Patriot, the 2000 Mel Gibson film about the American War of Independence, which landed the makers in trouble for, among other things, its portrayal (by a German director) of British atrocities that seemed to recall the worst excesses of the SS in the Second World War. How did he feel about it? " I've never seen the actual film," he says, "but I saw the scene in which the English herded people into a church and set fire to it. That never happened. But the English were ruthless and cruel in that war, no question, and there are certain things you can do to show cruelty."

Wilkinson was born 66 years ago in Yorkshire. He spent his earliest years on a farm outside Leeds. He remembers "hearing people say, 'That were t'night they bombed Kirkstall Forge' and thinking, what a wonderful name for a place". At four, his family moved to Canada. His father, a farmer, hoped to buy a farm on Vancouver Island, "but the woman who lived there wouldn't sell it to him, so he went to work in an aluminium smelter instead, as did my brothers."

Young Tom went to school in British Columbia. Did the kids laugh at his accent? "No – in the early 1950s, that part of Canada was full of immigrants. Nearly half the population was from Europe – Italians, Germans, English, Russians, the fall-out from war. I don't recall anyone saying, 'My Gahd you speak weird...'."

He was the baby of the family by 10 years. When he was in junior school, all his siblings were working at the smelter. Then a brother decided to go into computers instead. A sister got married. The smelting business declined – "and my mother decided she'd never liked Canada anyway". So the family returned to England and Tom's parents bought a pub in Cornwall.

Your father, I observe, sounds a very passionate, impetuous man. To up sticks, tear away from his roots, leave the country, relocate the family thousands of miles away – then turn round and come home again. "No," says Wilkinson, "he wasn't impulsive at all." He says it in a way that discourages further enquiries. Does he feel much connection with the North of England? "Well yes, I suppose," he says. "But I'm not sentimental about the place. It's certainly part of who I am but I'm not conscious of which bit. It's not unrelated to the fact that I don't want to be on the cover of the magazine. There's a feeling of, 'No, that's not for you – don't get ideas above your station'. A built-in reluctance."

After university in Kent, he joined Rada, "and I went straight into a part the day after I left. It was in The Mother by Brecht, at the Half Moon in Old Street. You didn't get any money, but you got Thursday morning off to sign on the dole."

His late twenties and early thirties saw "the usual progression that most actors had at that time – up and down the reps. I played leading roles, Hamlet in Coventry and Birmingham, Lear at the Royal Court, Henry the Fifth at Nottingham Playhouse." He spent a "fruitless" couple of years at the RSC, during the reign of John Barton and Terry Hands. "It was very inward-looking. People measured success by what other RSC people thought, as opposed to what the world thought." He began appearing on television: Inspector Morse, Prime Suspect. In Jeffrey Archer's First Among Equals, he played (appropriately) the MP for Leeds North. At 46, he was widely acclaimed for playing Seth Pecksniff in a TV version of Dickens's Martin Chuzzlewit.

"I'd got to the point where I could do more or less what I wanted on stage and TV," he reflects. "I wasn't offered soap operas, only heavyweight drama. The top echelons of TV would come to me." What did they see in him? He thinks for a moment. "What I was good at was making bad scripts seem good. I could do that. I don't mean producers said, 'Look, here's a piece of shit, can you make it seem good?'. I'd look at it and think, 'I've seen better writing than this, but let's pretend it's really worthwhile'."

One day, he decided to give up theatre and TV. He saw friends crossing the pond, making films in America, forging a new movie career. "I said to my agent, 'I don't want to do any more TV or stage. I just want films'." He'd appeared in a few movies, albeit briefly (in Ang Lee's Sense and Sensibility; he dies in the first scene), but then he went ballistic.

From 1996 onward, he appeared in three or four films a year. His range was hectic: he was Gerald in The Full Monty, Oscar Wilde's nemesis Lord Queensbury in Wilde, Hugh Fennyman the theatre owner in Shakespeare in Love, Dr Chasuble in The Importance of Being Ernest, Dr Howard Mierzwiak, the brains behind the memory-shredding system in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Carmine the Mafia boss in Batman Begins...

Two movies stand out from his torrential film CV. One is Todd Field's In the Bedroom, where he played a Maine doctor whose beloved son is killed by his girlfriend's ex-partner. Wilkinson's viciously destructive scenes with Sissy Spacek (playing his guilt-tripping, passive-aggressive wife) tore up the screen and knocked the critics for six. He won three Best Actor awards and was nominated for an Oscar. Speaking about it now, he'll only say, "Sissy is a fantastically professional actress, we'd rehearsed the scenes a lot, and it was a fucking good piece of writing".

The other high point is Michael Clayton, Tony Gilroy's 2007 legal thriller starring George Clooney. Wilkinson was a revelation as Arthur Edens, a senior lawyer who goes crazy in public and threatens to expose one of the company's crooked clients. His scenes with Clooney brought something wild, raging and very unsettling from this calm and contained actor. Where does it come from, his capacity for rage?

He sighs. "I've been doing this for about 40 years! People write stuff down, and I act it and I'm fucking good at it. I can be saying, 'Hello darling, how's things?' one minute, and do King Lear's rage the next, like that" – he snaps his fingers. "It's no good when a director like Todd [Field] says, 'OK Tom, whenever you're ready...' I said, 'Todd, you have to say action! You have to say now!' Because then you can go 'Click! I'm angry in this scene', or annoyed or suppressing something. It has to be like a light switch going on."

His next film is, a little surprisingly, a road comedy, Unfinished Business, with Vince Vaughn and Dave Franco, younger brother of James. How ambitious is he still? "I can't be bothered as much as I used to be. There's lots of stuff about filming I enjoy – I like the bit when somebody says 'Action', but the waiting around in hotel rooms, no. And they don't give you your envelope full of per diem dollars like they used to. Now it goes straight into the bank."

How does he feel about stardom? This is the man who famously failed to recognise Madonna when they met, and Julia Roberts. "Yes, it happens a lot," he ruefully admits. "But when you go up a red carpet, like at the Golden Globes or the Oscars, it's a fantastic experience." His eyes widen with genuine excitement. "You get to see really, really famous people and I still have this thing that I'm not really one of them. I just think, 'Fucking hell, so that's what Rupert Murdoch looks like,' or 'My God, Elton John's head is so big! It's huuuuuge!'."

And the self-effacing Mr Wilkinson spreads his hands to indicate the dimensions of a real superstar cranium, so unlike his own.

'Belle' is out now on general release

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments