George Martin: From comedy record producer to the 'Fifth Beatle'

Son of a street vendor, the late George Martin became known as a true gent in a nasty business. Now Beatles biographer Philip Norman traces his path from comedy record producer to the 'fifth Fab', and explains how he propelled them to stardom

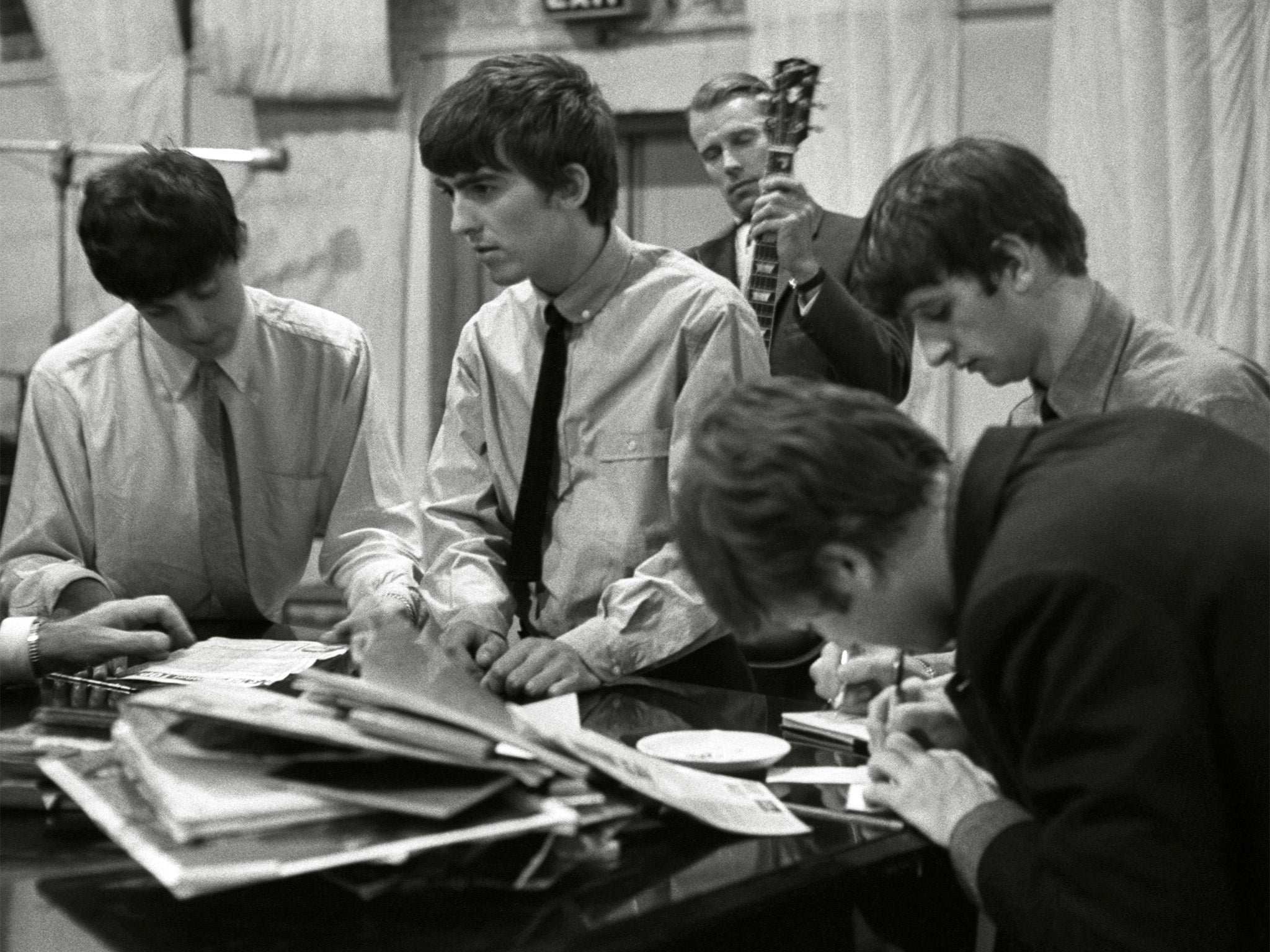

On 6 June 1962, a battered van arrived at EMI Records' studios in Abbey Road, north London. Inside were a four-piece pop group from Liverpool with a name which, at that time, seemed self-defeatingly weird: The Beatles. Their manager, Brian Epstein, had already pitched them to every other record company in London, without success. Their last hope was EMI's small Parlophone label, run by George Martin.

Martin, then 36, was a tall, elegant man with the impeccable diction of a BBC newsreader and, Epstein later recalled, the air of a "stern but fair-minded schoolmaster". Yet over the next seven years, this unlikely figure was to become The Beatles' indispensable collaborator in some of the most magical pop music ever recorded. And in all his dealings with John, Paul, George and Ringo, he would prove a shining exception in an industry where ruthless exploitation and double-dealing are the norm. George Martin was not only one of pop's greatest producers; he was also, unquestionably, its greatest gentleman.

In reality, Martin was nothing like the toff that the Liverpool lads first took him for. He grew up in a poor family in north London, where his father had once sold newspapers on a street corner. His cut-glass accent had been acquired during wartime service with the Fleet Air Arm, then while studying the oboe at London's Guildhall School of Music and Drama.

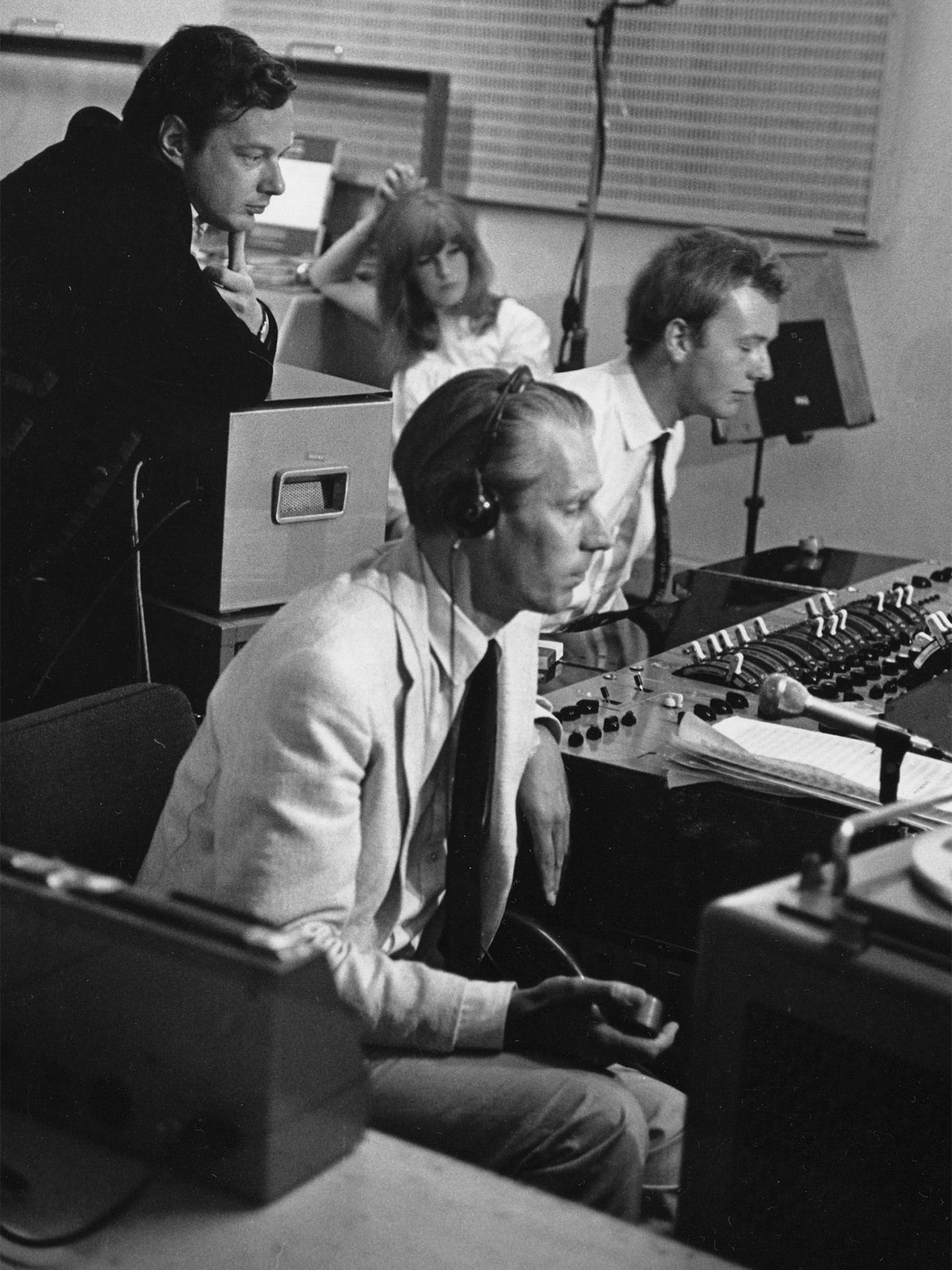

He joined EMI in 1950, in an era when recording studios were like laboratories, engineers wore white coats and performers worked under the total control of all-knowing in-house producers.

In 1955, he became London's youngest record-label boss, at only 29, unusually combining his executive duties with producing, talent-scouting, composing and arranging. And until he met The Beatles, Parlophone had had only a few pop hits: with The Vipers Skiffle Group, comedy-jazzers The Temperance Seven, and balladeer Adam Faith.

The label was known chiefly for classical and "light orchestral" music, comedy albums by The Goons and Peter Sellers, and live cast recordings of West End shows such as At the Drop of a Hat and Beyond the Fringe.

Creating comedy albums was a long, laborious process compared with releasing pop singles. Martin had long envied his fellow EMI label boss Norrie Paramor, of Columbia, who'd discovered Cliff Richard and the Shadows and who now had hits effortlessly rolling out like cars on a production line.

Martin had agreed to audition The Beatles largely in the hope of finding his very own Cliff Richard and the Shadows. Unfortunately, the Liverpudlian quartet didn't conform to the usual "beat group" formula of single lead vocalist and support musicians. John, Paul and George all took turns at lead-singing, and back-up vocals and harmonies were integral to their act. Martin considered making Paul the sole vocalist just because he was "the prettiest". However, he had the wisdom to leave the configuration as it was.

When he first mentioned his new acquisition to his EMI bosses, they were assumed to be fodder for another of his comedy records. "The Beatles!" echoed one, with a snort of derision. "Is it Spike Milligan disguised?"

John Lennon and Paul McCartney had been writing songs together almost since first meeting at a Liverpool church fete, five years earlier. But The Beatles also had accumulated a huge repertoire of cover versions to get them through their marathon sets at Liverpool's Cavern Club and in Hamburg's red-light district. The main reason for their previous rejection by Decca Records was an audition full of eccentric choices such as "Red Sails in the Sunset" and "The Sheik of Araby".

At that time, it was almost unknown for British artistes to record their own compositions. Nonetheless, Martin decided that The Beatles' first single should be Lennon and McCartney's "Love Me Do". The producer's traditional absolute authority was to be short-lived. When "Love Me Do" just scraped into the UK Top 20, Martin planned that The Beatles' follow-up would be a perky little number entitled "How Do You Do It?" by the "professional" songwriter Mitch Murray.

However, defying all precedent, they protested that it "wasn't them" and lobbied vigorously for another Lennon-McCartney composition, "Please Please Me". Though not best pleased, Martin agreed to let them record it. After the first take, he switched on the studio intercom and said, "Gentlemen, you have just made your first No 1." And in March 1963, so it proved – on the New Musical Express and Melody Maker charts, if not quite on what is now known as the official singles chart.

The band's huge success from then on provided many opportunities for Martin to enrich himself. In those days, it was standard practice for record producers to take a slice of the publishing royalties on songs recorded under their aegis. Under a less scrupulous producer, John and Paul's work could easily have borne the credit "Lennon-McCartney-Martin", or The Beatles could have been made to record songs written by Martin as B-sides or album tracks. But Martin practised none of the scams open to him – indeed, he sought no reward but the satisfaction of turning raw talent into polished hits.

After The Beatles' breakthrough came a string of so-called Merseybeat acts also managed by Brian Epstein – Gerry and the Pacemakers, Cilla Black, Billy J Kramer and the Dakotas – for whom Epstein decreed George Martin to be the only possible producer. In 1963, he had a UK No 1 single for 37 weeks out of 52, yet was still on his EMI salary of £3,000 a year. To add insult to injury, a recent minor pay rise disqualified him from that year's staff Christmas bonus.

Even after The Beatles' conquest of America in 1964, they were generally regarded – and, indeed, regarded themselves – as merely a passing craze whose popularity could evaporate at any moment. To get the most possible mileage from them, Martin imposed a punishing schedule of a new single every three months and a new album every six, to be fitted in somehow between touring, television and radio appearances, and film-making.

Yet despite this pressure, their recorded output was always fresh and surprising thanks to John and Paul's blossoming genius as songwriters and Martin's dedication to helping them to expand their musical boundaries.

Only in the very early days did Lennon and McCartney physically write together. Although their joint credit continued, each now developed his own songs in private, then played them to the other – and their producer – for criticism and recording ideas.

John was the more easygoing, usually happy with whatever setting Martin devised. On his sweetly autobiographical "In My Life", for instance, he simply left a space for "instrumental break", then went off with his bandmates to lunch. During their absence, Martin composed and taped a piano passage reminiscent of Bach, then adjusted the recording speed to make the piano sound like a harpsichord. John was delighted. Paul, by contrast, always knew precisely how he wanted his songs arranged but – being unable to read or write music himself – depended on Martin to turn his increasingly ambitious concepts into reality.

In 1965, during the making of the Help! album, he brought in a song that had come to him in a dream, a plaintive ballad provisionally entitled "Scrambled Eggs", later renamed "Yesterday".

Martin scored it like a classical piece and Paul recorded it accompanied by a string quartet, with none of his fellow Beatles participating. "Yesterday" went on to be covered by more than 2,000 other acts and to top innumerable polls as the 20th century's favourite song. Martin's single blind spot, he once told me, was failing to see any potential whatsoever in George Harrison and, on occasion, being "rather beastly" to him. This further stoked George's frustration and resentment at being eclipsed by the Lennon-McCartney creative juggernaut.

The wild fashions and fancies of the Swinging Sixties had no effect on Martin: he remained short-haired, dapper and disapproving of the emerging drug culture of which The Beatles were to become figureheads. When they smoked pot, they took care never to do so in front of him, disappearing into the EMI toilets like naughty schoolboys smoking behind the bike sheds. Martin produced their LSD-soaked masterpiece, Sgt Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, without ever taking a trip himself – while being responsible for the album's trippiest moment.

Its closing track was John Lennon's haunting "A Day in the Life", for which John wanted to end with "a sound building up from nothing to the end of the world". To achieve this, Martin hired a 41-piece symphony orchestra to perform in full evening dress, plus clowns' red noses and fake gorilla-paws distributed by The Beatles. There was no written score: Martin simply gave the orchestra a top and a bottom note and told them to play whatever cacophonies they wished in between. Aside from The Byrds' "Eight Miles High", drug-delirium has never been better captured in sound.

After Brian Epstein's death from a barbiturates overdose in 1967, Martin was one of The Beatles' few stable points as they searched for a new manager, flirted with transcendental meditation, made their disastrous Magical Mystery Tour film, and plunged into their hippy-idealistic business empire, Apple Corps.

But the harmony there had always been at Abbey Road Studios ended with the project known as the "White Album", though its official title was The Beatles. John had just gone public about his affair with Yoko Ono, whom he saw not only as a lover but a creative partner to replace Paul. Obsessed with Yoko, he insisted on having her with him in the studio and consulting her first about everything The Beatles laid down. Martin was appalled, though – gentlemanly as always – he kept his feelings to himself.

The next album, originally titled "Get Back", was an attempt to restore the band's unity by returning to their roots in rock'n'roll and R&B. As John told Martin ungraciously, it had to sound like a live performance, without overdubs or "any of that production shit". The recording sessions, filmed for an accompanying documentary, were a purgatorial experience, with Yoko there continually, John strung out on heroin, George finally turning on Paul for having bossed him around for so many years, and John and George actually coming to blows. In the end, Martin could stand no more, and bowed out.

With Get Back retitled Let It Be but seemingly in limbo, he was surprised to receive a phone call from Paul, asking him to return to the studio with The Beatles and make one last album "just like we used to". He agreed, on condition they behaved just like they used to, with no more quarrelling or backbiting. The result was Abbey Road, an album bathed in the sunshine of the 1960s' closing year, on which the soon-to-fractured Fab Four never sounded closer.

By the time Let It Be finally came out, in 1970, The Beatles were effectively disbanded. Their latter manager, Allen Klein, had hired the American producer Phil Spector to remix the album, adding melodramatic strings and heavenly choirs. Martin commented that its credit should read "Produced by George Martin, over-produced by Phil Spector".

During the 1970s, Martin developed his own independent AIR studios, with premises in London and on the idyllic Caribbean island of Montserrat. The world's leading rock acts naturally flocked to work with The Beatles' former producer, among them Elton John, The Rolling Stones, Pink Floyd – and Wings, the band that the solo Paul McCartney formed with his wife, Linda, on keyboards. In 1989, AIR's Montserrat studios were destroyed by a hurricane. Martin, who had come to love the area, found personal refuge on the neighbouring island of Nevis.

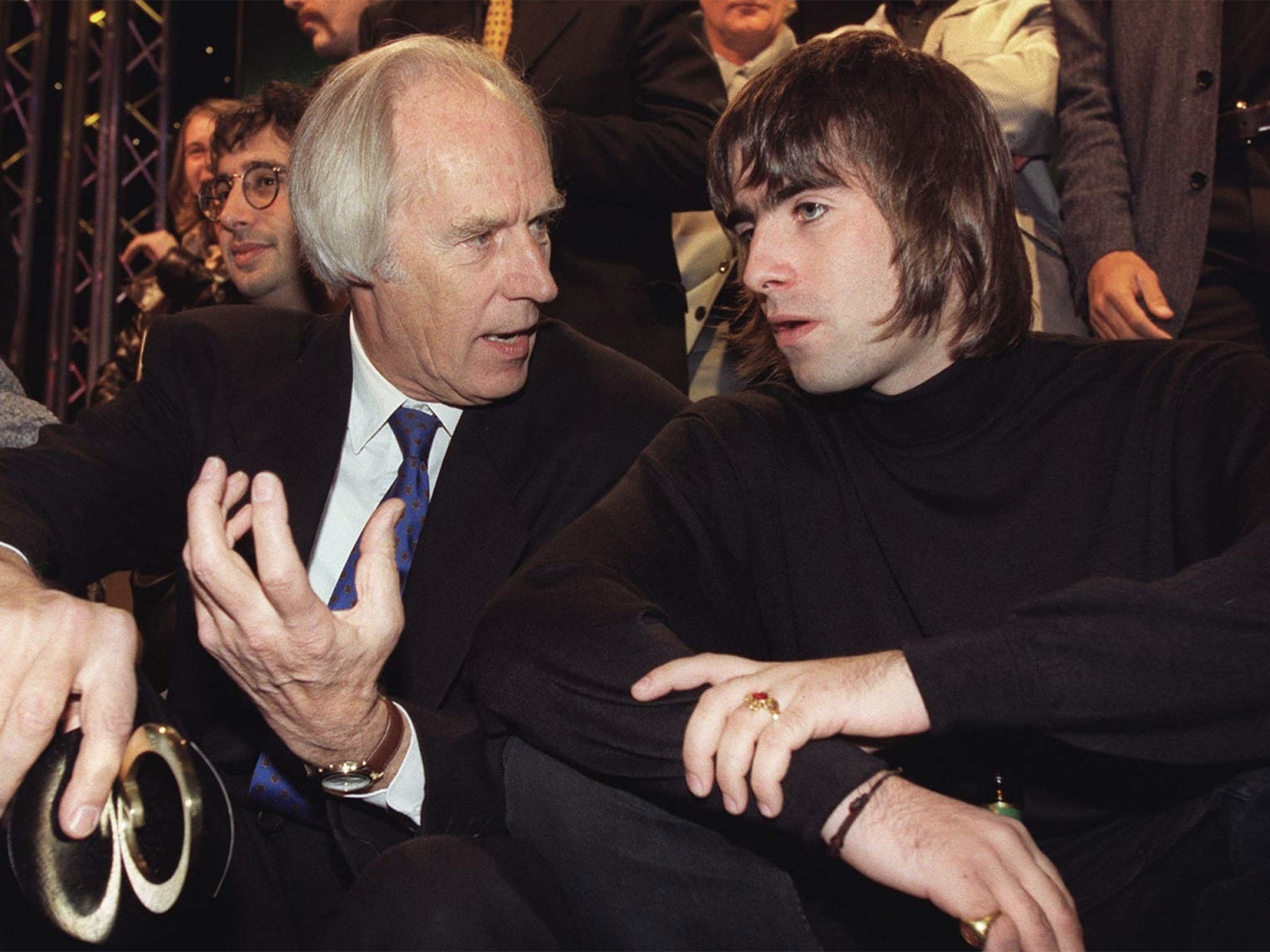

He was appointed CBE for services to music in 1988 and knighted in 1996, a year before Paul McCartney was. And the link with his greatest pop protégés was to prove unbreakable. In the mid-1990s, he compiled The Beatles Anthology, a three-CD set of rarities and studio out-takes, released along with a multi-part television documentary and an illustrated book.

His autobiography, a pun on The Beatles' great Flower Power anthem, was All You Need Is Ears. Sadly, the price of decades of fastidious listening was progressive hearing-loss, which increasingly obliged him to use his son, Giles, as an amplifier.

Father and son worked together on a final Beatles project, the soundtrack for Cirque du Soleil's Love musical, which opened in Las Vegas in 2006 and is a continuing smash hit.

Uniqueness in pop music is a rarity. Just as The Beatles were unique, so was their producer: uniquely nonconformist, uniquely talented, uniquely honourable, uniquely respected, uniquely charming.

Philip Norman's books include the Beatles biography 'Shout!' and 'John Lennon: The Life'. He is also the author of 'Paul McCartney: The Biography', to be published by Weidenfeld and Nicolson on 5 May

'As much as anyone, the midwife to the Swinging Sixties'

By Andy Gill

What do the following have in common: Rolf Harris, The Mahavishnu Orchestra, "Nellie The Elephant", The Archers and "Revolution #9"? The answer, of course, is George Martin, producer of all the above and the man largely responsible for transforming the drab austerity of the Fifties into the gaudy funfair that was the Swinging Sixties.

His influence on pop-culture was colossal – and not simply as The Man Behind The Beatles. Even before he stumbled across the Fab Four, he'd already served in the trenches of Fifties light music, and sowed the seeds that would determine the comedy landscape of the Sixties through his recordings of Spike Milligan, Peter Sellers and the Beyond The Fringe team. "Goodness Gracious Me"? That was George. Michael Bentine reading the football results? George. "Any Old Iron"? "Right Said Fred"? Yep, George, too.

No one was immune to his influence, either: while their parents hummed along with The Archers them or tapped their tootsies to The Temperance Seven (both George's), the Fifties war babies could tune into Uncle Mac on a Saturday morning and be subjected to a non-stop barrage of George Martin productions: "Nellie The Elephant", "The Hippopotamus Song" (aka "Glorious Mud"), "Robin Hood", "My Boomerang Won't Come Back", "My Brother"… just listing the titles brings back the taste of cod liver oil and welfare orange juice.

In an age of micro-specialisation, it's hard to understand the sheer diversity of Martin's CV. His career began in the stultifying Fifties, when authentic unbridled fun seemed almost a treacherous betrayal of the era's austerity. And though his work with comedians hinted at an anarchic side, George's early productions revealed an odd combination of eclecticism, fastidiousness and innate conservatism – which would prove the perfect foil for The Beatles' unvarnished gifts in the early Sixties, making him the ideal executor of their more outlandish ideas later that decade, pushing the envelope with groundbreaking productions of avant-garde masterpieces such as "A Day In The Life".

The Beatles, of course, were a tough act to follow – and when they called it a day, Martin struggled to find artists of comparable talent. (He displayed a particular affinity, however, for recording high-calibre jazz guitarists such as John McLaughlin and Jeff Beck.) Then again, it would be asking an awful lot for one person to sustain for longer than a decade or two his catalytic effect on post-war British culture. He'll be forever remembered as The Man Behind The Beatles, but Martin's influence goes further: as much as anyone, he was the midwife to the Swinging Sixties.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks