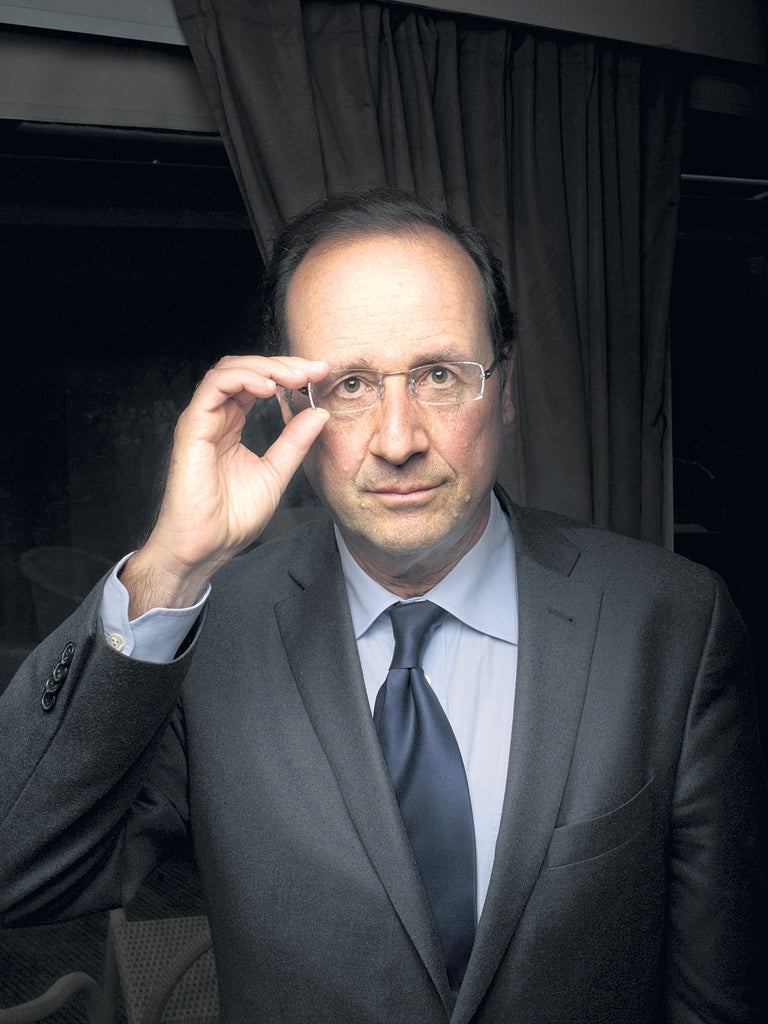

François Hollande: Gallic charm offensive

With France going to the polls in the spring, the Socialist challenger to Nicolas Sarkozy is proving very persuasive

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Our first scene is a campaign meeting in Corrèze in south-western France in June 1981. A bespectacled young man from Paris with unruly hair and a cherubic face stands up to heckle Jacques Chirac.

The young man accuses "Le Grand Jacques", local hero and a rising star of French politics, of "cowardice". There is a stunned silence in the hall: then howls and boos.

The interloper is the Socialist parliamentary candidate, parachuted into Corrèze by the recently elected president, François Mitterrand. The young man from Paris complains that he challenged Chirac, in writing, to a public debate. Chirac had not even replied.

For our second scene, again in Corrèze, we fast-forward exactly 30 years, to June 2011. Former president Jacques Chirac is chatting to the local MP and leader of the Corrèze council, one of several Socialist candidates for president in 2012. The two men, nominally political enemies, are evidently chums.

Though thinner now and balding, Chirac's ambitious pal is recognisably the young heckler-candidate from 1981. Spotting a TV camera, Jacques Chirac, one-time mentor of President Nicolas Sarkozy, decides to create a political incident. "I am voting for François Hollande for president," he announces. "Why shouldn't I vote for François Hollande?"

If the opinion polls are to be believed, millions of French voters are asking themselves the same question. Why shouldn't they vote for François Hollande in the two-round presidential election on 22 April and 6 May?

With just under three months to the first round of voting, Hollande, 57, has a comfortable lead over President Sarkozy in the first round and a crushing lead in the two-candidate run-off. Much can yet happen in three months. Two other candidates, the far-right leader Marine Le Pen and the centrist François Bayrou, are hard on Mr Sarkozy's heels. As things stand, France, faced with domestic economic crisis and potential European cataclysm, is contemplating a new left-wing president for the first time in three decades.

Unlike Tony Blair in 1997, Hollande does not claim to have invented a magic new formula, or even shiny packaging, for the centre-left. Unlike François Mitterrand in 1981, he is not threatening a programme of red-blooded Socialism. Instead, Hollande claims, rather unnervingly, to be a "normal" man who would be a "normal" president in anything but normal times.

Who on earth is François Hollande? Should we all be scared of him, as Boris Johnson implausibly claims?

The two incidents in Corrèze tell you some of the things that you need to know about Hollande. First, he has pluck and cheek. Second, he is an irresistibly likeable man. Third, he worked hard for three decades to turn himself from party apparatchik into a provincial baron, rooted in the rural soul of France. Fourth, he is neither a left-wing ideologue nor a tribal politician.

Hollande has been until now a social-democratic, political professional – a manager, a safe pair of hands. He is the antithesis of the wheel-spinning movement-without-progress of the Sarkzoy years. That is his principal appeal.

François Gérard Georges Hollande was born on 12 August 1954 in Rouen in upper Normandy. His father, Georges, was a doctor and a would-be politician of the nationalist far right, a believer in "Algérie Française" and a sworn enemy of President Charles de Gaulle. Hollande's mother, Nicole, was a social worker with left-wing views.

The family moved, when young François was 14, to Neuilly-sur-Seine, the wealthy Parisian satellite town which was also, curiously, the boyhood home of Nicolas Sarkozy. The young François, rebelling against his father, became a follower of François Mitterrand, the perennial candidate of the left in the 1960s and 1970s.

He went to law school and business school, to the elite political school Sciences Po, and, finally, to the finishing school of the French elite, the Ecole Nationale d'Administration (ENA). His fellow pupils included the future centre-right prime minister Dominique de Villepin and Hollande's future "wife", Ségolène Royal.

In three decades in politics, Hollande has never held any ministerial position. His mentor, François Mitterrand, decided to promote Royal. Mitterrand thought that husband-and-wife teams in cabinet were not a good idea – even if the couple were not actually married.

Hollande rose instead as a provincial politician and a national party operator, which is not a contradiction in terms in France. He was economic attaché to President Mitterrand when France tried to drive down the wrong side of the Reagan-Thatcher monetarist motorway in the early 1980s.

He became a kind of spiritual son of Jacques Delors, the future president of the European Commission. He became the Socialist Party's leader, or first secretary, when Lionel Jospin was elected prime minister in 1997.

He watched aghast as Royal ran unsuccessfully for president in 2007. The couple had, in fact, parted in 2006 but disguised their separation for political reasons. They have four children, now aged 19 to 27. Some friends still insist that revenge on her ex-partner was one of Royal's principal motivations for running last time. Hollande had started a relationship in 2006 with the woman he now describes as the "love of his life", Valérie Trierweiler (left), a TV and magazine journalist.

When Hollande decided 15 months ago that 2012 would be his "turn", few people took him seriously, even in the Parti Socialiste. The overwhelming favourite to win the Socialist nomination was the former finance minister and IMF chief, Dominique Strauss-Kahn. Hollande was mocked by the influential, satirical, TV puppet show Les Guignols de l'Info as "Flamby", a caramel pudding, a man who preferred to make a joke rather than risk a decision or an idea.

Even before DSK was arrested in New York last year, Hollande was rising, almost unnoticed, in the polls. He had gone on a crash diet; he had stopped making jokes (to the disappointment of some). When DSK was forced out of the race, Hollande became the Socialist front-runner and comfortably won the party's first ever "open primary" – ie open to all French voters – in October.

In his first big campaign meeting last Sunday, Hollande took Sarkozy's centre-right party and many of his own supporters by surprise. He showed powers of oratory and self-projection that neither had thought possible. He declared his intention to "reinvent the French dream". He outlined a prudent, mildly left-leaning programme in radically left-wing language. He declared "big finance" to be his enemy but his proposals to vanquish the banks sounded largely David Cameronesque (ie dividing them into high street and speculative institutions).

Hollande also made a silly gaffe in quoting "Shakespeare", not realising that the quote came from Nicholas, the contemporary British writer, rather than the great William. He made a similar gaffe in 2006 when he was photographed reading a book called French History for Dummies. But his campaign, compared to that of Royal, has been notably gaffe-free until now.

Also idea-free? Hollande's 60 proposals to reform France, published on Thursday, amount to moderate, leftist tinkering rather than revolution. He promises to expunge France's 5.2 per cent of GDP budget deficit in five years. He also promises an extra €20bn for schools and job creation. The sums are induced to add up by new taxes on the rich and largely unspecified savings.

Hollande also promises to reopen the debate on the future of the euro by convincing Berlin, he says, to allow the European Central Bank to guarantee all eurozone debt. He will persuade Angela Merkel to promote growth, not just austerity. Here, too, Hollande sounds more like David Cameron than Karl Marx.

Europe and the world, not just France, are crying out for new leadership and for big new ideas. François Hollande is likeable, reliable, pragmatic and, suddenly, eloquent. But, to date, he promises little more than small, old ideas and more muddle.

A life in brief

Born: François Gérard Georges Hollande, 12 August 1954, Rouen, France.

Family: His mother, Nicole, was a social worker; his father, Georges, an ENT doctor. He has four children with his ex-partner, the Socialist politician Ségolène Royal.

Education: HEC Paris business school, Ecole Nationale d'Administration, Strasbourg, Institut d'Etudes Politiques de Paris.

Career: Joined Socialist Party in 1979. First Secretary 1997-2008. Mayor of Tulle 2001-2008. Official Socialist Party and Radical Left Party presidential candidate in 2011.

He says: "My real adversary will never be a candidate, even though it governs. It is the world of finance."

They say: "He believes in the religion of compromise. He will be the hostage of his own party." Nicolas Sarkozy

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments