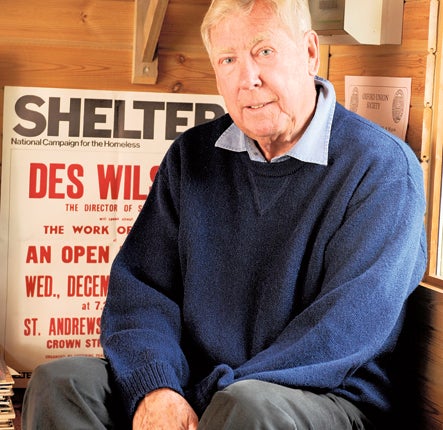

Des Wilson: 'We can only try to edge the world in the right direction'

If charities are the future, they could do worse than follow the example of the great Des Wilson. Robert Chesshyre met him

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When a man the world takes to be intensely ambitious writes a memoir flatly refuting his ambition, do we believe him? Des Wilson (for the benefit of younger readers) shot to fame in the 1960s. He had youth, antipodean egalitarianism and astounding energy, and he became both the first director of the housing charity, Shelter, and the man who dislodged the Lady Bountiful tradition of British charities – replacing it with the hard-edged campaigning we know today.

His career later embraced a string of successful campaigns (for lead-free petrol; against smoking; for freedom of information; for Sunday shopping) as well as the chairmanship of Friends of the Earth and the presidency of the Liberal Party (the last before the party's merger with the Social Democrats), and (much to his delight as a cricket nut) membership of the English Cricket Board (ECB).

To his critics, Wilson was a rubber ball who bounced in from New Zealand in 1960 and irritatingly never stopped ricocheting: to his admirers he was a breath of much needed fresh air who blew away some of the cobwebs then (even more than now) wrapped about British public life.

He has now written Memoirs of a Minor Public Figure, to coincide with his 70th birthday this week, an account of one of the more erratic high-profile odysseys of recent times. Wilson argues that, had he been genuinely ambitious, he would have dedicated himself to one task and reached the very top. His dipping here and there is evidence of his lack of a world-conquering plan.

I have known Wilson for 40 of his 70 years, and have always found him an engaging and loyal friend, dedicated to the causes he championed. I can, however, see what got up some people's noses – the endless chirpiness, the apparent self-satisfaction, the trumpet-blowing. We British like a bit of stiff-upper lip, not a Wilson characteristic. But, beneath the perkiness, there is a man who has always cared passionately and is refreshingly self-aware.

Ten years ago Wilson removed himself to a comfortable, utterly isolated, cottage in Cornwall (certainly no Cold Comfort Farm), in the middle of fields. Water comes from a borehole, and an oil-fired Rayburn hums in the kitchen. It is a most unlikely removal for a man once so busy at the centre of affairs.

The onetime gadfly of London life is still instantly recognisable: in jeans and a striped pullover, as unconcerned as ever about his appearance. His hair, touched now by grey, remains unkempt, and he bursts into infectious laughter when, as often, he finds something funny. There yet linger traces of the wild colonial boy.

As the light fails, a flock of pigeons descends on the cauliflowers outside. Wilson's artist wife, Jane Dunmore, apart, who is working in her studio, the birds appear to be the only life within miles.

"You must remember," Wilson starts, "that I was a small-town boy. It was no trauma to move here.'"His journey from Oamaru, a community of 8,000 souls halfway down the east coast of New Zealand's south island, to London and rapid success could stand comparison with Dick Whittington's arrival in the capital. Wilson disembarked aged 19 on 10 June, 1960, with a fiver in his pocket.

He was soon reduced to sharing his last egg-and-tomato roll with an Aussie mate in an Earls Court bedsit. He had flogged his typewriter, and was saved from penury by the editor of an Australian news agency, who confused Wilson's enthusiasm for cricket for a love of tennis and sent him to cover Wimbledon at £12-a-week.

Wilson still describes his trade as "journalism" rather than campaigning; it was, he says, his reporter's training to tell stories that lay behind the success of his crusades. In Oamaru he discovered that volunteering led to an inside track, and that you made people take note by making a noise. Publicity was his currency, and he spent it – not, he says, to promote himself (that was a by-product), but to advance the causes he espoused.

Wilson wasn't a cradle radical, rather an egalitarian who from childhood believed that no one should push him around. It was John F. Kennedy and his 1961 inaugural address ("Ask not what your country can do for you...") that opened his eyes to what could be achieved through public service.

Like much else in Wilson's life, Shelter just happened. The Rev Bruce Kendrick, who ran the Notting Hill Housing Trust, wanted to create a "domestic Oxfam": Wilson, tired of wasting energy passing resolutions at the Twickenham Labour party saw Cathy Come Home, the 1965 TV drama that woke the British to the fact that – 20 years after the end of the Second World War – there were still 3m people living in near-Dickensian homes. He volunteered.

Kendrick sent him on a slum tour, and Wilson came back with "Road to Wigan Pier" descriptions of misery, damp, over-crowding, outside cold water taps. "I'd open a door and find a whole family in one room, with one filthy shared toilet." Shelter was born. Soon Wilson was its director – and a national figure.

The charity establishment was then mainly comprised of retired military men. One ex-officer on his staff burst into Wilson's office spluttering indignantly: "There's a homeless family in the lobby." "Well," said Wilson, "we are the national homeless campaign.2 "Be that as it may," said the ex-officer, "I worked for the World Wildlife Fund and we didn't have tigers roaming the corridors." More seriously, Shelter's charity rivals suggested that, by making waves, Shelter was clearly "political", thus contravening strict charity neutrality rules. "It was a bit late," says Wilson. "Imagine the uproar if the Charity Commissioners had said that they were going to tax Shelter's income as 'political'."

By then the Beatles had become international stars; Carnaby Street and the King's Road rocked in psychedelic colour; the age of youthful celebrity had dawned. Wilson was just the man to shake a bit of that stardust over charities.

After five years he moved on, exhausted from criss-crossing the country delivering his stump speech. Shelter may have directly helped "only" a few thousand people, but it had changed the national agenda. Oxfam approached Wilson to be its director. He didn't get the job – one of his few regrets – and he returned to writing, most notably a campaigning column for The Observer.

"Did it help being born outside the British class system?" I ask. "Without any question," comes the instant reply. He does rue missing out on higher education, and recalls walking in Cambridge and seeing "these fantastic buildings. I thought 'God, these people have no idea how lucky they are'."

Wilson's mid-career zigzagged like a runaway bobsleigh: PR (for, among others, the Royal Shakespeare Company), journalism, campaigns. He was offered a Labour Parliamentary seat, but he was too individualist to knuckle down to the required doctrinaire discipline. He became a Liberal overnight when invited to fight the 1973 Hove by-election. Politically, he had found his home, though only accepting the nomination after being assured he couldn't win.

Wilson in this memoir is at his most readable when most self-deprecating. One story relates a lunch at Buckingham Palace at which Wilson's brashness apparently displeased the Queen herself and princes Philip and Charles. Shortly afterwards he found himself on a plane next to the courtier who had organised the meal. Des sought reaction to his lese majeste. "Oh don't worry, Mr Wilson," said the courtier, 'Her Majesty is used to meeting all sorts."

Darkness has fallen and the pigeons are long departed. "Is it 5.30 yet?" Wilson asks. It was a magic hour as that had been pub opening time when Wilson landed in Southampton. We poured glasses of wine and visited the garden cabins where both Jane and Wilson work. Jane has the grander one, a former small chapel brought to the site by a previous owner of the cottage.

Posters, books, mementoes from that life five hours away by train to Paddington crowd Wilson's walls. There is room for a small snooker table on which Wilson opens an ancient cuttings book stuffed with reports of far off cricket games, augmented by lists of Wilson's World XIs written in boyhood pencil.

I ask if the rumour I had heard that he had been offered a knighthood was true. Wilson makes the required noises about not speaking of such matters, and then agrees that he did pass up "an opportunity". It struck him only later what pleasure the honour would have given his mother on the far side of the world. He would still have said No, though recognises that this might have been "selfish".

We return to ambition. "If I was ambitious, I was f**king incompetent at it," says Wilson. "I didn't set out to change the world; the book title was carefully chosen. We can only be expected to edge the world in the right direction. I have done things that have made a difference, and I am satisfied."

'Memoirs of a Minor Public Figure' is published by Quartet Books on 7 March

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments