David Hockney: A man aflame – and long before the smoking ban

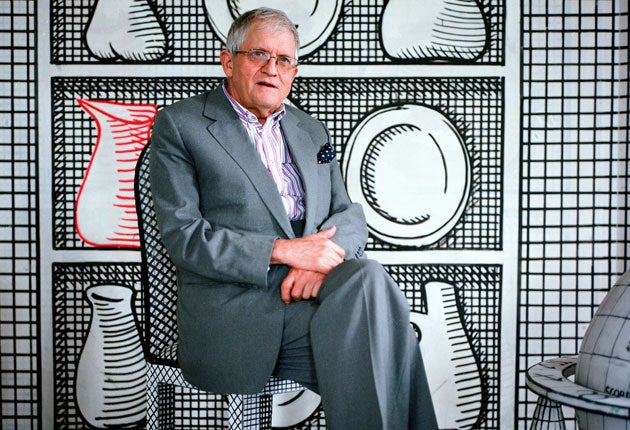

Iconic artist, evangelical smoker and avid technophile, the boy from the Broad Acres looks forward to a new season at Glyndebourne. Michael Church meets David Hockney

Jim's always on time," says the headline in the advert over a grinning face, and then adds "No wonder – he's got a wizard Ingersoll Eagle Watch". Defiantly drawing all day in the bottom stream at Bradford Grammar, 15-year-old David Hockney had sent this in for a newspaper poster competition in 1952, and got pushed into second place by a 16-year-old named Gerald Scarfe.

Fast-forward 24 years, and these artists were again in competition, and again unaware of it. Glyndebourne director John Cox was looking for a designer for Stravinsky's The Rake's Progress, and Scarfe had been mooted, but Cox demurred. For this story about the death of innocence, he wanted an artist whose work projected a love of humanity, and Hockney was his choice.

The benefit worked both ways: the show was a hit, and Hockney was freed from the constricting academicism that had threatened to become his prison. The painter of portraits such as Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy – once voted fifth in a BBC poll to find "the greatest painting in Britain" – was liberated in a way he might otherwise never have been by this invitation to paint the stage.

Fast-forward 35 more years, and Glyndebourne's longest-running production is being revived yet again. The new cast is as good as the one that launched it, and the painter emerges visibly excited from his first rehearsal. This production, he says, has always worked beautifully. "A film-scholar friend of mine who saw the last revival said: 'It was terrific – not like an opera, very entertaining." But I never understood why anybody could think opera was boring: it's the most spectacular theatre you ever see. Only the dull find opera boring."

Now 73, Hockney looks notably trim and elegant, and – in constant transit between his studios in Bridlington, Kensington and Los Angeles – he's on the crest of a wave. He's pioneering new ways of representing nature with cutting-edge technology; he's preparing a show that will completely fill the Royal Academy in 2012; and he's still producing a painting a day. His appetite for challenges is still insatiable, as it was when Cox issued his original invitation: "I said I wasn't sure I knew enough technically, and he replied that you didn't need to know that much about it. So I said OK, I may fail, but I'll do my best. And as I started to listen, I realised that Stravinsky was cleverly acknowledging the 18th century, so we should find a way to do that."

He decided to use Hogarth's cross-hatched engraving style: this would be a drawn stage, rather than a painted one.

On the star-studded opening night, Cox asked him if he'd like to design The Magic Flute, and thus began a new career. "I love working in the theatre," Hockney says. "The people are tolerant, they know about human frailty, they're not mean-spirited as most people seem to be in England today."

Then it's as though a switch has been flipped. "I was at a hospital in Hull the other day, and there's a big notice 'No smoking in the building or the grounds'. I'm going to write to them. All it shows is mean-spiritedness – and that's not good for health, is it? I'm going to tell them that. I'm fed up with the negativity of this country. People should speak up. I worked in the NHS as a hospital orderly during my national service, and people thought it was a noble service. But over the years it's lost its humanity." He's making a serious point, but this is the grumpy-old-man mode the tabloids love: mustn't let it take up too much of our time.

Glyndebourne's fanciful sets for the Hockney Flute were subsequently destroyed in a warehouse fire, but the production was revived to acclaim in America, after which he created a series of shows that have revolutionised opera design.

Will he ever design another? He sidesteps the question with a reference to his now (quite advanced) deafness. "I can still enjoy music, but I'm not hearing everything, and I'm deeply affected by unfocused sound. The only place I listen to music now is in my car, a big Lexus which has very little ambient noise. It has 18 speakers – terrific. Here in Glyndebourne I'm probably filling in things, because I've got a lot of music in my head, as I always did. I was brought up with John Barbirolli and the Hallé, and in my teenage years I learned to listen to music. Listening is a positive act: you have to put yourself out to do it. It's like looking. I think most people are pretty blind now."

Would he like to elaborate on that? No, because without missing a beat he continues his train of thought, explaining how after 25 years in California he found himself making an unexpected discovery on his regular visits home. "As I was losing my hearing, I was also noticing that I was seeing Yorkshire clearer. I can't hear spatially – I can't tell where a sound is coming from – but my visual spatial awareness was increasing dramatically. So for me this disability was an advantage." And he discovered something else: "In southern California you don't have seasons. When I realised I could watch seasons again in Yorkshire, I'd found a subject I hadn't yet dealt with." Looking at nature has now become an addiction: "I'm very touched by what Van Gogh said: he'd lost his father's faith, but he'd found another one in the infinity of nature."

Then comes a gear change. "Did you see Avatar? I go and see anything that's visually new, any technology that's about picture-making. The technology won't make the pictures different, but someone using it will." And out comes his iPhone. "I did this drawing with my finger this morning." It's of an armchair with a shirt and trousers flung over it, very Van Gogh in its bold detail and exuberant primary colours. "Now watch. It will play back the drawing, exactly as I did it but speeded-up. I've never been able to see myself draw before."

Then he produces his famous iPad. "Now I'll show you a small reproduction of what I made with nine cameras." Whereupon we're in Woldgate Woods, a giant image of whose leafless winter trees dominated Tate Britain two years ago. "It's all high definition, on nine screens. This was a misty morning, 6am – we're right in a dark wood. Now watch it come out of the mist." The foliage advances gently and gracefully.

These Yorkshire trees are very like his assemblages covering a wall in the Royal Academy's current summer show. Is this a harbinger of his giant Olympic-year exhibition? "No, that will be mostly landscape paintings. And some are very, very big. Look at this." On his iPad there now appears a painting by Claude Lorrain entitled The Sermon on the Mount. It's a landscape dominated by a mysterious bushy hill, and it's dark and discoloured with age.

"The museum gave me a disk of it," says Hockney, "which I then digitally cleaned." He has: all the detail in the next image on the iPad is fresh and bright. "Then I began doing my versions of it." He starts scrolling rapidly from right to left, to reveal the hill and its inhabitants in a succession of guises: some echo the playful charm of his Sixties paintings, others evoke the Fauves and Picasso. The grandeur of his vision – and the rate of his productivity – takes the breath away: this is an extraordinary revelation. "That one is 15ft high by 24ft. It's now in the studio in Brid. One painting on 30 canvases, so we can move it. I am always painting on the floor, so I don't need a ladder."

The whole exhibition is going to be called, appropriately, A Bigger Picture. "And that great big painting is going to be called A Bigger Message. I think paintings should be big now." Moreover, a year ahead of schedule, the show is virtually all done. Seb Coe and his cronies don't deserve such an amazing windfall.

Nine years ago Hockney went out on an art-historical limb by publishing a book called Secret Knowledge. In it he argued that the Old Masters of the 16th century used the fact that mirrors and lenses could project a subject on to the surface of a painting: he's still sore at the way the art-history establishment collectively froze him out. "In this 400th anniversary of Caravaggio's death, there have been many articles about him, but it's clear nobody really knew why he was important. And the reason is big. He was the first artist to paint such deep, dark shadows.

"Now you might ask, as I did 12 years ago, how did he get this? And why is it that in any art outside of Europe – Chinese painting, Japanese painting, Indian, Persian – there's no shadow? The shadows occurred suddenly in Europe, first around 1420, but Caravaggio represents a big jump. We know he painted very fast, that he never left a drawing, and there's no record of him making any, so how did he construct those pictures? I concluded he was using optics directly, and we figured out how. Art historians don't like somebody coming in like this from the outside, but I'm positive I'm right, and one day people will agree with me."

And this, he adds, doesn't just alter the history of photography: this technological-intellectual jump, he says, has its parallels in the media today. After the hegemony of the church came the hegemony of Rupert Murdoch; after Murdoch will come a new era in which newspapers and television are supplanted by YouTube and i-apps. "I can draw on this every morning" – brandishing his iPhone – "and send the drawing out to my friends. I can watch films on my iPad, and I can find a picture of Renoir smoking on it. I can read on it. Last Sunday four newspapers were delivered to me in Bridlington. I weighed them – three kilos, all schlepped to Bridlington. I like newspapers, but in the end these things will win, because all that schlepping costs money."

Then, after a pause: "But there are limitations to the technology. I send out 300 drawings to friends, but they can only look at them one at a time. So how do you show a body of work? An old-fashioned exhibition! And that's what we are going to do with my iPhone drawings in Paris later this year. This is about bringing back the hand: I'm making drawings on a printing machine. This has brought some excitement into what is in many ways a dreary age. Something very mean-spirited."

Whereupon that switch is flipped again. By the time John Cox and the Glyndebourne press officer arrive to extract him, he's mid-stream in an unstoppable tirade against the anti-smoking joylessness of York, Liverpool and other points north. "Yes, I'm angry. People have to speak up."

So we must wait until our next interview to discover whether he still regards A Bigger Splash as an "aberration" from the true line of his artistic development; whether it's true that, as his chronicler Jonathon Brown believes, he stopped painting his trademark cut flowers in the Eighties as an anguished response to Aids; and whether he would still define his artistic duty – as he once memorably did – as being "to overcome the sterility of despair".

Do the answers to such questions matter? Yes, because we don't need opinion polls to tell us that this is the artist who has for decades been painting the backdrop to our lives.

'The Rake's Progress' opens at Glyndebourne today, and continues in repertory until 29 August

Curriculum vitae

1937 Born in Bradford to a "radical working-class family".

1948 Wins scholarship to Bradford Grammar School.

1953 Enrols at Bradford College of Art.

1957 As a conscientious objector, works as a hospital orderly during national service.

1961 Features in the Young Contemporaries exhibition which marked the arrival of British pop art.

1962 Graduates from the Royal College of Art. Awarded its Gold Medal for outstanding distinction.

1963 Visits New York and befriends Andy Warhol. Moves to Los Angeles.

1966 Meets his early model, Peter Schlesinger, who becomes his lover.

1970 Begins to work in photocollage after piecing together Polaroid pictures of a room he is painting.

1971 Completes Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy, depicting Ossie Clark and Celia Birtwell – the only work by a living artist in the BBC's greatest British paintings vote in 2005.

1982 Begins creating Joiners, collages using photos from different viewpoints to create a sense of space and time passing.

1987 Returns primarily to painting but experiments with new technologies, including laser printing.

1991 Elected to the Royal Academy.

1997 Becomes Companion of Honour.

2001 Publishes his theory that the Old Masters used camera obscura techniques.

2005 National Portrait Gallery shows a major exhibition of Hockney work.

2007 Creates his biggest work, Bigger Trees Near Warter, of a grey day in Yorkshire. He donates it to the Tate.

2009 Begins using the Apple iPhone to create new work.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks