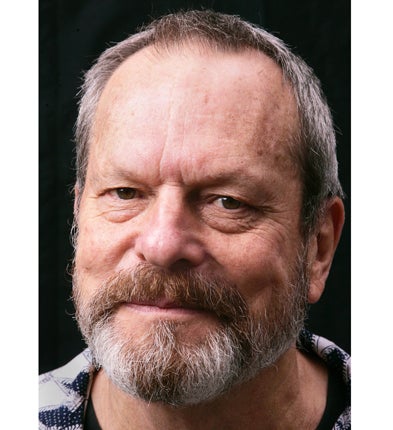

Cursed genius: Terry Gilliam

Bad luck seems to hover over the visionary film director, but even the death of his leading actor has failed to stop his latest work

Hollywood is a town that indulges superstition. So when Heath Ledger died in January last year during the shooting of his final film, The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus, it was said that a curse cast on its director, Terry Gilliam, had struck again. Gilliam's filmography, after all, is littered with as-yet-unrealised projects, budget busts and studio battles.

Parnassus, many believed, was doomed to the same fate as his Don Quixote movie, which so far has made it to the screen only as the subject of Lost in La Mancha, a documentary chronicling the production's descent into chaos – courtesy of biblical weather, the ageing lead's ill health and the Spanish air force conducting exercises near the set.

Yet far from proving the curse of Gilliam, the release of Parnassus on 16 October demonstrates his unique brilliance. For what other film-maker could, through the sheer force of his imagination, take such a tragedy and turn it into a tribute to his friend and fallen star? And how many directors are so beloved by Hollywood's brightest and best that they could enlist Johnny Depp, Colin Farrell and Jude Law to finish the job?

Parnassus tells the winding tale of a travelling actors' troupe led by the titular doctor; they move between the banality of modern London and a mystical netherworld, picking up players along the way – including Tony, a ne'er-do-well who helps them in their quest to rescue the doctor's daughter from the devil, as played by Tom Waits. Tony looks like Ledger in London, and like Depp, Farrell or Law after passing through the doctor's looking glass into the netherworld. It is, like many a Gilliam film, a little hard to explain without the pictures.

Christopher Plummer, who plays Parnassus and worked with Gilliam on Twelve Monkeys, recently told an interviewer that the director had himself blamed the jinx that appeared to afflict his films for Ledger's death: "[Terry] is a very dear soul underneath all that wacky stuff, a very emotional man," he said. "He's half genius and half madman. I'm crazy about him."

Gilliam's singular imagination first corrupted popular culture in 1969, when the 29-year-old émigré animator became a member of Monty Python's Flying Circus. Born in Minnesota in 1940 and schooled in California, he moved to England in his twenties, where (having already met John Cleese when he visited the US with the Cambridge Footlights) he worked with Michael Palin, Terry Jones and Eric Idle on the children's comedy series Do Not Adjust Your Set. Life as a Python followed, and if John Cleese was the group's comic genius, then Gilliam was behind its unforgettable visuals.

Contrary to popular perception, however, Gilliam's visions weren't fuelled by mind-expanding substances – a notion he would also have to dispel after his drug binge road movie Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas in 1998. "When Python used to be reviewed," he says, "they all thought we were druggies. Me, in particular."

In his diaries, Palin recalls his friend's disillusionment with animation as early as 1972. Gilliam was running out of ideas and keen to write and direct live action, so in 1975 he and Jones co-directed Monty Python and the Holy Grail. By the time the Pythons began to disintegrate in 1979, Gilliam had, in Palin's words, an "almost all-consuming urge to do his own movie... Otherwise, he says, he will go mad".

That movie was Time Bandits (1981), a fantasy jaunt through time and space with an unmistakable feel that marked out Gilliam as an auteur, and gave him the opportunity to follow it with his pet project, Brazil (1985). Though now considered by many as his masterpiece, this oddball Orwellian dystopia sparked the first of Gilliam's many battles with the studios. Not for nothing are his films shot through with a hatred for bureaucracy and bland authoritarianism. Universal, responsible for the film's US release, insisted on re-cutting the bleak ending, and Gilliam fought the decision tooth and nail.

Eventually he had his way, but his reputation was further muddied by his next feature, The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1988), which made back less than a fifth of its budget at the US box office, earning its director the enduring title of troublemaker and liability. In fact, in the years that followed, Gilliam proved himself more than able to deliver studio-financed pictures on time and on budget, with The Fisher King (1991) and Twelve Monkeys (1995), both critical and commercial hits.

He even succeeded in filming Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas where Martin Scorsese and Oliver Stone had failed. In the meantime, however, he was denied the opportunity to work on some larger prestige projects. An adaptation of Watchmen, the classic graphic novel that finally made it to the screen this year directed by Zack Snyder, passed across his desk twice; besides the difficulty of raising funds for such an ambitious film, Gilliam decided the original material would be better served by a mini-series.

Gilliam was frustrated when Warner Bros refused his bid to direct the first Harry Potter film. As J K Rowling's first choice of director, he was flown to LA for the requisite meetings, but even if the studio was keen, the insurance companies knew his record, and would have demanded too high a premium. "I was so angry at myself for fooling me into getting excited about it," he later admitted. "There was no way I was ever going to make [Harry Potter]. I knew that... It's an acceptance of the reality of Hollywood."

His most recent works are a failed attempt at a commercial hit, The Brothers Grimm (2005), and Tideland (2005), a wantonly dark fantasia seen by almost no one. Thanks in part to the success of Lost in La Mancha, Gilliam has started to be talked about as a visionary who simply can't translate his genius into a coherent movie. But, says Ian Freer, assistant editor of Empire, "If you wrote a list of all of his films, only about 10 per cent of them genuinely fail – and those are noble failures. Compared to most film-makers, that's a pretty good batting average. He can sometimes let his creativity outpace his care, but I wouldn't want him to not do that – it would stop him being himself."

Because of his troubled history with the studios, Gilliam – now 68 – accepts that his future lies in independent film-making, and the next project on his slate is a familiar one: The Man Who Killed Don Quixote, for which he has re-acquired the rights and plans to finally deliver by 2011. Empire, meanwhile, has described Parnassus as his best work in more than a decade, not least because it returns him to the mad world of his own imagination.

Gilliam himself claims Parnassus is like his version of Bergman's Fanny and Alexander or Fellini's Amarcord. "Those directors reached a point in their lives where they said, 'OK, let's just wallow in the things we enjoy.' So this is my wallow. I don't have to keep proving new things and exploring all areas. This is what I am. This is what I do."

Says Freer: "There's an argument that actually Gilliam remakes Alice in Wonderland every time. Parnassus is very much a trip through the looking glass. And it has the visual excitement that you want from Gilliam. I wonder how many of us are left who really want the Gilliam thing, but hopefully, given that it's got Johnny Depp, Jude Law, Colin Farrell and Heath Ledger in it, he'll find some new people to excite."

As to the reworking of the film following Ledger's death, "If it had been a different film-maker it might not work," Freer goes on, "but in Terry Gilliam's world, you can try things and change it. It's a testament to his style. Maybe it's something he's learnt over the years – to endure the chaos that comes with making his films."

A life in brief

Born: Terence Vance Gilliam, 22 November 1940, Medicine Lake, Minnesota.

Family: One of three siblings. His father James Hall Gilliam was a travelling salesman and carpenter. Married the British make-up and costume designer Maggie Weston in 1973. They have three children who often appear in Gilliam's films.

Career: Started his career as an animator and strip cartoonist on Help! (1965) and animated Monty Python's Flying Circus from the first episode (1969). Directed a number of films including Jabberwocky (1977), Brazil (1985), The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1988), Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1998), The Brothers Grimm (2005) and The Imaginarium of Dr Parnassus (2009). He is rumoured to be working with Damon Albarn's Gorillaz on a new film project. Gilliam was given the Bafta Academy Fellowship Award in 2009 for his contribution to motion picture arts.

He says: "You get trapped by stories. Though I've got this reputation for being out of control, it's not true. It just happens to be a more interesting story than the truth."

They say: "I love Terry and personally I'd do anything the guy wants to do." Johnny Depp

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks