Brian Wildsmith: Technicolor artist of wonder and beauty

He is such a well-regarded illustrator of children's books that he has a museum dedicated to his work in Japan. So why is he barely heard of here? Susie Mesure meets Brian Wildsmith

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

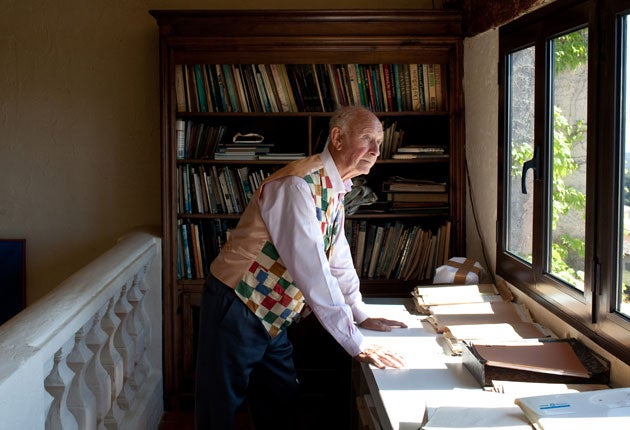

Your support makes all the difference.Brian Wildsmith lives for colour. So he takes it personally that his beloved Côte d'Azur vista, the backdrop to his world for the past four decades, is a muted patchwork of murky grays and navy blues for my fleeting visit.

"I had so hoped it would be sunny for you," he says, greeting me at his hillside home in the outskirts of Nice with a Gallic double kiss on both cheeks. "You see, I get depressed when the sun is clouded over. It affects me." I am hardly surprised. After all, Wildsmith is an illustrator who made his name in a rainbow explosion back in the early Sixties with the simplest of children's books, an illustrated ABC, that set a brightly coloured flame burning throughout the publishing world.

Even now, the prolific artist turned author, who has written 82 books, thinks that first one was his best. "It was the time of Carnaby Street and The Beatles. There was a new era of creativity in England, and that book was the beginning for a creative expanse of children's books."

The critics thought so too; the book won the prestigious Kate Greenaway Medal in 1962, the year after it came out. To make up for the drab view – on a clear day we would be gazing out to the Mediterranean and one of Picasso's former homes – he brings out two glasses of champagne, apt given that this year is one of celebration for Wildsmith, not least because he recently turned 80. This month sees the first serious exhibition of his work at a London gallery – it's the first time his original illustrations are on sale in the UK – plus another show at Seven Stories, Newcastle's museum of children's books.

And Oxford University Press, his publisher, is reissuing some of his out-of-print titles in special editions.It's all part of a belated attempt to pay homage to a man who, despite inspiring some of the best-known names in the business, including the former and current Children's Laureates Michael Rosen and Anthony Browne, is no Eric Carle when it comes to children's books. Not that he lacks Carle's talent; Wildsmith's brushstrokes are more than a match for the American illustrator. But unlike Carle, Wildsmith had no Hungry Caterpillar equivalent to plaster all over everything from children's party plates to umpteen versions of the same title.

This was no accident, he explains. "A lot of illustrators have one central character and then they develop it, and all their books are based around it. But that was not my wish. I wanted to introduce children to the whole creative side of many aspects of life."

Soon after that first ABC, Wildsmith's editor, Mabel George, encouraged him to turn his hand to writing, as well as illustrating stories. "I said, 'But Mabel, my English is terrible. I always got terrible marks at school.' But she said, 'Brian, I have editors with inkpots full of full stops and commas. It's ideas that count and you've got them.' And it took off from there."

His books, which have sold more than 20 million copies around the world, have something of a didactic theme, spanning La Fontaine's fables to the stories in the Bible. Many have a moralistic tone – like the one about the owl and woodpecker who initially hate each other but end up getting along. Or they teach children about concepts such as collective nouns: Animal Gallery includes such delights as a leap of leopards, a party of rainbow fish and a crash of rhinoceroses. But what they don't do is risk boring a child with too many words. The pictures are key, whether of the donkey carrying the crucified body of Jesus to his tomb in the Easter Story, or the hare charging away from the tortoise in Aesop's fable.

This is markedly different from the sorts of children's books that Wildsmith, or indeed Michael Rosen, grew up with. As Rosen puts it: "My childhood was full of books, but just as the Sixties burst into life, there seemed to be something similar happening in children's books. Floors of colour exploding across the pages with a name to match: Wildsmith. He was a wild smith. I remember feeling really envious: why hadn't I had books as lush and wild as these?"

Or as Wildsmith explains: "[Before ABC] the text was the most important thing and pictures would just accompany it, diagrammatically explaining what was going on in the words. But I could limit my text so the illustrations explained what actually happened. And not just the physical event of what was happening, but the vision of the people or the animals or the landscape around them. I was expressing in colour the wonder and beauty of the world in which we live, which had never happened before, and would have been difficult to explain in words for children."

Despite those sales figures and the idyllic-looking life that he and his wife have clearly enjoyed in their beautiful French stone house since the parents-of-four emigrated in 1971, all is not quite right in the Wildsmith world. Whether it's the curse of the expat (although his wife Aurélie is half- French, the illustrator is pure Yorkshireman), Wildsmith has issues with his mother country, where he feels he is underappreciated – and worse.

"I've never been invited to do an exhibition or do a talk in England, except once, about 10 years ago. I've given talks all across Canada, many in the United States, South Africa, Singapore, Hong Kong, Japan – but not England. There, people want me out of the way because I'm a threat to their Comic Cuts attitude to children's books. Not that there's anything wrong with comic books or Mickey Mouse, but it just another different side to producing works for children. I mean, I don't dislike those, I like Mickey Mouse, but there's another side." It's clearly a sore point. "It's like food. I mean, do you just let your kids eat lollipops and ice cream or do you give them nourriture?"

To feel the love, Wildsmith has had to head even further east. To Japan, in fact, where the debonair Brit is practically a cult figure. There is an entire Brian Wildsmith-dedicated museum just outside Tokyo and the last exhibition of his work drew a crowd of 1.2 million. He has even illustrated four children's books by Daisaku Ikeda, head of the controversial Buddhist sect Soka Gakkai, which has such a strong following, including among Hollywood A-listers such as Orlando Bloom and Tina Turner, that many fear its controlling influence.

Wildsmith believes his popularity in Japan throws up some important cultural distinctions. "The Japanese are incredibly cultured. In England, there is a dividing line between artists and illustrators, who are thought inferior to painters. Well, that's absolute rubbish. Some of the most creative work is being done in children's books. In Japan, everything is art. They don't say painting is better than ceramics or dress design."

The artist-versus-illustrator conundrum is a sensitive one for Wildsmith, who won a scholarship to the Slade School of Fine Art in London after three years at Barnsley College of Art, in South Yorkshire, near where he grew up. He hadn't intended to be an artist, but a last-minute calling prompted him to drop his plans to be a scientist. "A voice in my head said, 'Is this what you want to do?'"

He was largely self-taught. "The art at school was a disaster. All we did was sit in a circle around cubes and triangles and draw them in different positions.... It was during the war so paper was scarce and it was difficult to get paints, but I used to spend my time drawing battle scenes between airplanes and warships."

He taught art briefly after leaving the Slade, but saw a future as a book illustrator. "I read that 28,000 books a year were published and I thought, they'll all need book wrappers, so I spent my evenings designing them." Eventually he quit his day job, approached OUP and found his calling.

Though he claims not to have any regrets about not pursuing a fine art career – "there's no way I can grumble about sales of 20 million" – you can't help feeling a little more recognition at home, his UK home, would provide the icing on the 80th birthday cake. As he admits: "Every artist who's ever lived wants to be appreciated by everybody. It's just part of being an artist, whether you're a singer, a musician, a painter or an illustrator. We want to be appreciated – that's why we do it. It's your expression, but it's really for other people."

Judging by the rate that collectors are snapping up his drawings, Wildsmith might yet hit Eric Carle status.

Brian Wildsmith exhibition, The Illustration Cupboad, 22 Bury Street, London, SW1Y 6AL, until 24 April

Win! A Brian Wildsmith signed print

We're offering readers the chance to win a signed limited-edition Brian Wildsmith print of the parrot and jaguar from his Jungle Party book, worth £650.

To enter, draw or paint an unlikely pairing of two animals that could feature in your own children's book, explaining your choice. Brian Wildsmith will help choose a winner. Entries must be received by Friday, 21 May 2010. Don't forget to include your name, address, email, and phone number.

Submissions to: Brian Wildsmith competition, c/o Colin Wilson, Art Director, Independent on Sunday, 2 Derry Street, London W8 5HF. Full competition rules at: independent.co.uk/legal

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments