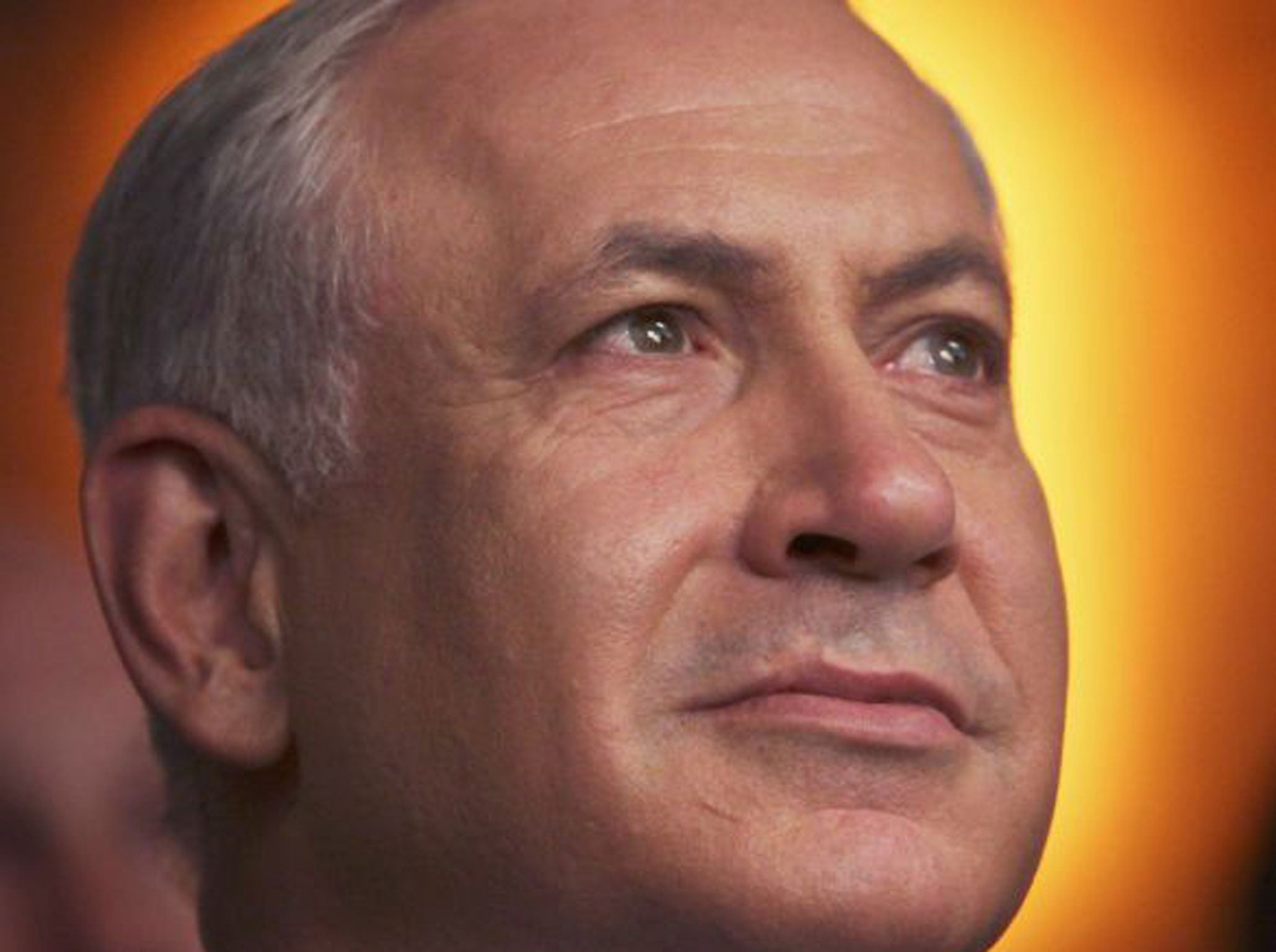

Benjamin Netanyahu: The talker turns fighter

As Israel once more stands on the brink of war, is its leader showing an unseen side?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.On Thursday evening, Israelis saw their Prime Minister as they had never seen him before. It was not his demeanour that was different. Benjamin Netanyahu can do statesman's gravitas as well as anyone. Nor was it the staging: the formality of the patriotic blue backdrop and the furled Israeli flags that framed his televised press conference in Tel Aviv tends to follow him wherever he goes. It was the reason for his appearance. This was the first time that Netanyahu had addressed the country as a war leader.

He was speaking a day after an Israeli air strike had killed the leader of the military wing of Hamas in Gaza, at the start of an operation called Pillar of Defence, and just a few hours after air-raid sirens had warned Tel Aviv of incoming rockets for the first time in more than 20 years. Answering questions with his customary assurance, the Prime Minister warned Hamas that if rocket attacks from Gaza continued, "Israel is prepared to take whatever action is necessary to defend our people". In moves that some saw as supportive bluff and others took at face value, his press conference was preceded by the announcement of a call-up of reservists and reports of troops being moved up to the border.

For those around the world who incline to discern a warrior, if not a warmonger, in every Israeli leader, it might come as a surprise to learn that this was the first time in a total of seven years as Prime Minister that Netanyahu had publicly authorised military action. And while that might in part reflect the passing of Israel's first generation of warrior leaders, the relative stability of Israel's borders over those years, and the chance timing of his return to the premiership – after Israel completed its controversial Gaza offensive, Operation Cast Lead – it also says something about the man.

Although he served in Israel's Defence Forces with distinction – he became a team leader in the elite special forces unit, Sayeret Matkal, and served on the frontline in the 1973 Yom Kippur war – he is not seen, nor would he probably see himself, as a military man. He is, above all, a professional politician – in fact, one of Israel's first – and, second, by quite a long way, a successful businessman.

Indeed, on military matters, as on much else, he has always been cautious throughout his near 40-year career, always preferring a technocratic and economic approach to one that entails the use of force. It would be easy, though probably wrong, to suggest that he was put off all things military by the loss of his elder brother, Jonathan (Yonno) – the commander and the only military casualty of the now legendary Entebbe raid. But the truth is that by his late teens, Benjamin Netanyahu's life was already taking another course – and one that could have taken him far from his native Israel.

He spent much of his childhood in the United States, where his father was an academic specialist in Jewish history, and returned there after military service to take degrees in architecture, politics and business. That US experience has left its imprint. Almost the first thing anyone would notice on meeting Netanyahu is not only his immaculate American-accented English, but how much he retains a certain East Coast American manner and style. He has few of the rough edges that define less cosmopolitan Israeli politicians. He carries himself with confidence and, away from the public platform, he is soft-spoken.

Netanyahu's American years were supplemented by stints in business consultancy and in diplomacy – at Israel's Washington embassy and as ambassador to the UN – which may also have contributed to the impression he gives that anything is possible between reasonable people. Israel's domestic politics can seem raucous, verbally brutal and coarse. But this is not Netanyahu's way. When he transferred to politics, as he did on his definitive return to Israel in 1988, he brought with him an air of being somehow apart that gave him a reputation for coldness and led him to be dubbed a lone wolf.

This did not mean that he underestimated the need for alliances. In the fractious world of Israeli politics, bridge-building and horse-trading are key to survival. And in Likud, the party that traditionally stood above all for security, there was plenty of that to be done, starting inside the party. At the same time, Netanyahu has always seemed less amenable to compromise than many, and always prepared to walk away, as though he knew that, if need be, he could do something else.

From the post of deputy foreign minister, which he obtained after he was first elected to the Knesset, it took him just eight years to rise to Prime Minister – the youngest and the first both to be directly elected and to have been born in the State of Israel. He was helped on his way by internal rivalries in Likud, from which he astutely kept aside, and indirectly by the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin, which precipitated early elections. It was May 1996, and he was 47, with a solidly successful career behind him and no particular sign of trouble ahead.

In the three years he spent as Prime Minister, before his coalition fell apart, he came across as a brasher, more self-confident and more irascible character than he is now, in his second time around as head of government. But his view of the world, and his priorities as an Israeli, have remained remarkably consistent. Already evident was the sense of history and identity instilled by his professor father; the profound loyalty to Israel that brought him back from America; the idea that freeing up the economy could help to solve other problems along the way, and the preference for reaching solutions by talking rather than fighting – either figuratively or literally.

Even in those years, which followed what was in retrospect the heyday of Israeli-Palestinian talks, Netanyahu took a hawkish position on Palestinian statehood. A veteran at the negotiating table, he was always wary about giving something for nothing. Israel's security was always paramount. He was nonetheless forced into retreat and came under fire from the right of his party for agreeing to talk to Yasser Arafat.

But that first term as prime minister was not only complicated by internal party squabbles, but tarnished by the sort of simmering scandals about appointments and the buying of influence which have continued to plague Netanyahu. His penchant for American-style campaigning, his friendships with prominent businessmen, his – some say – undue concern with public relations all left their mark. And although no prosecution has ever succeeded, Likud's defeat in 1999 was widely seen – and cheered in many quarters – as spelling the end of his political career.

His wife Sara also gained a notoriety of her own; complaints of her behaviour towards domestic staff, including one in which a maid broke a finger, and accounts of her entourage on privately funded foreign trips found their way into the media and prompted litigation.

In the event, the election defeat of 1999 represented little more than a pause. Returning to government in 2002, Netanyahu served as foreign minister, as an unexpectedly successful, if not particularly popular, economics minister, and won the premiership for a second time in 2009, after four years as leader of the opposition. He must now count as one of the most seasoned politicians in Israel, and possibly anywhere in the world.

And the consistency in his thinking over the years lends a particular significance to parallels between his two prime ministerial terms. Netanyahu may, since President Obama's grand overture to the Muslim world in his Cairo speech, have reluctantly accepted the principle of Palestinian statement – but not without strings that in many ways negate the very essence of statehood.

He was also quite clear in his view of Gaza as a threat to Israel's security from early on – he lost the 1999 election after rocket attacks multiplied – and he resigned from Ariel Sharon's government in 2005, rather than vote for the last stage of Israel's withdrawal from Gaza. For all his reluctance to embroil Israel in a new war, his present hard line is entirely consonant with those misgivings – and with the imminence of an election in January.

What happens next, though, is qualified by two imponderables. For all Netanyahu's familiarity with the United States – perhaps even because of it – his relations with Obama have been almost uniquely bad. Niceties are observed; they talk about being the closest of allies; that Obama sees Netanyahu as a stubborn block to progress on Palestinian statehood, however, is barely concealed.

And then there is the centrality for Netanyahu – some say his obsession – with the threat he sees from a nuclear Iran. Whether it is Israel's own defence establishment that has so far kept Netanyahu's supposed desire to strike in check, or dire warnings from Washington, barely matters. There are those who see Israel's current offensive in Gaza as a rehearsal or, less ambitiously, a substitute for a strike on Iran.

Netanyahu was born the year after the foundation of the state of Israel, and his life and career mirror its fortunes in many respects. The decisions he takes in the next few weeks will determine not only his own electoral chances in January, but also the fate of a whole region, perhaps even of the world.

A Life in Brief

Born: Benjamin "Bibi" Netanyahu, 21 October 1949, Tel Aviv, Israel.

Family: The second of three sons of Zila and Benzion, a historian. Married to Sara Ben-Artzi (two sons, one daughter).

Education: Attended school in Jerusalem and Philadelphia. His studies of architecture at MIT and political science at Harvard were interrupted by active service in the IDF.

Career: Ambassador to the UN, 1984-88. Joined Likud and elected to the Knesset in 1988. Has served twice as Prime Minister, in 1996-99 and from 2009 to the present.

He says: "There are those who say that if the Holocaust had not occurred, the state of Israel would never have been established. But I say that if the state of Israel had been established earlier, the Holocaust would not have occurred."

They say: "Bibi has two types of friends: those he has betrayed and those he will betray." (Anonymous)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments