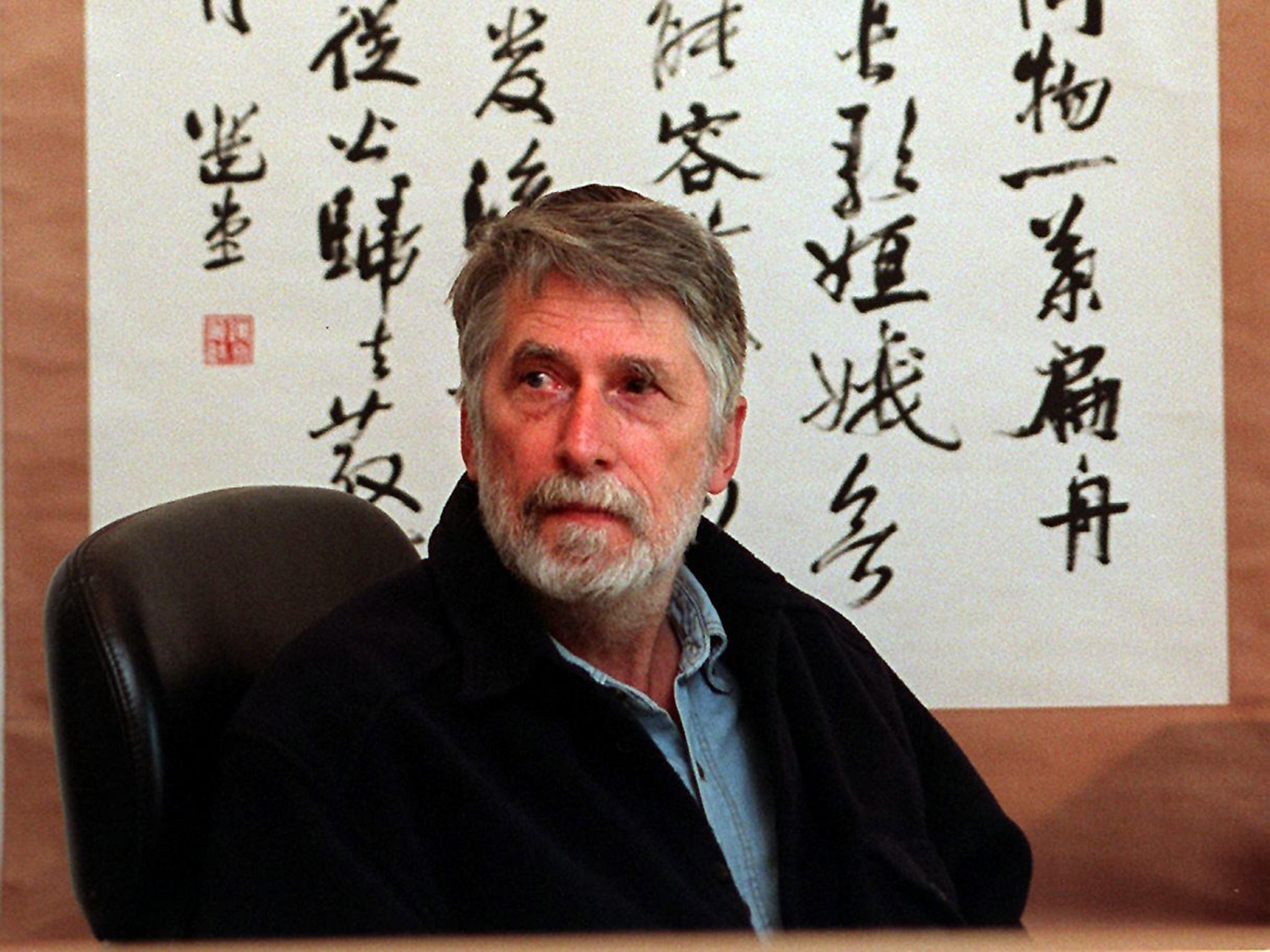

Professor Pierre Ryckmans: Sinologist and one of the first to reveal the shocking reality behind China's Cultural Revolution

Ryckman’s intellectual life was wide-ranging, cosmopolitan and outspoken, reflecting in his many books and essays, usually written in French, his interests in art, literature, history, politics and philosophy

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Pierre Ryckmans was an author and Sinologist who flew in the face of the popular romantic left-wing Western view of China of the 1960s and ’70s and exposed Chairman Mao’s rule and the Cultural Revolution’s darker side.

For his 1971 exposé on the Cultural Revolution, The Chairman’s New Clothes, written originally in French, Ryckmans adopted the lifelong pseudonym Simon Leys on the advice of his publisher to avoid being banned from China, as his book was politically explosive with its portrayal of Mao’s Cultural Revolution as chaotic and destructive.

Mao had initiated the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution in 1966; the aim of the programme, which lasted 10 years, was to remove “counter-revolutionary” elements in Chinese society and Western capitalist influences and replace them with Maoist orthodoxy; it was marked by violent class struggle, widespread destruction of cultural artefacts and the unprecedented elevation of Mao’s personality cult.

Ryckmans believed that the Cultural Revolution had destroyed the beauty of Chinese culture and civilisation without destroying what needed to be banished, the tyranny of arbitrary rule. He became one of the first Western Sinologists to expose the truth of the cultural desecration that occurred during the Cultural Revolution by ripping away the thin political veneer and exposing it for what it was: an ugly, violent, internal political struggle within the Chinese Communist Party led by Mao Zedong. Ryckmans said his aim was “not to question the achievements” of the regime, but to add “some shadows, without which even the most luminous portrait lacks depth”.

His books triggered outrage and controversy, particularly in Europe, but Ryckmans said, “I was merely stating common sense, evidence and common knowledge, [which] may have disturbed some fools here and there.”

He was condemned by Sinologists who had been taken in by the romance which many felt for the Cultural Revolution in its early days. Ryckmans was later “outed” by a fellow academic, although he retained his alias. A second book, Chinese Shadows (1974), again written under his nom de plume, followed a six-month assignment in 1972 as a cultural attaché for the Belgian Embassy in Beijing.

When Mao died in 1976 the Chinese leadership renounced the Cultural Revolution as a “severe setback” and “The Great Disaster”; Ryckmans rightly surmised that although there would inevitably be a relaxation of authoritarian rule, the fundamental characteristics of Communism would not change. Later critics and historians characterised Mao as a dictator who oversaw systematic human rights abuses, and whose rule is estimated to have contributed to the deaths of between 40-70 million people through starvation, forced labour and executions.

Born in Brussels in 1935, Ryckmans had an enjoyable childhood, with, he said, “warm affection and much laughter”. He studied law and art history at Louvain University.

What he described as his “love affair” with China began in 1955 following an invitation from the Chinese government for a delegation of young Belgians to visit the country for a month. It culminated in an audience with Premier Zhou Enlai, Mao’s lifelong lieutenant.

Ryckmans returned with a firm view that “it would be inconceivable to live in this world, in our age, without a good knowledge of Chinese language and a direct access to Chinese culture.” As China was closed to Westerners except for restricted short visits, he went to Taiwan to study Chinese art, culture and literature and completed his doctorate. There he met his wife, Han-fang Chang. He also taught at the university and in Singapore and Hong Kong.

Following an invitation in 1970, Ryckmans and his family moved to the Australian National University in Canberra. In 1987 he moved to the University of Sydney as Professor of Chinese Studies, focusing on literature and art until his retirement in 1993.

Ryckman’s intellectual life was wide-ranging, cosmopolitan and outspoken, reflecting in his many books and essays, usually written in French, his interests in art, literature, history, politics and philosophy. The book that brought him to popular attention in Europe was the award-winning novel, The Death of Napoleon (1992). In it, the Emperor escapes from the island of St Helena, where he is impersonated by a petty officer, and returns to France in an ill-fated attempt to regain power.

It was later filmed with Ian Holm in the title role, but Ryckmans was disappointed by Alan Taylor’s direction; Holm’s performance, he said, “made me dream of what could have been achieved had the producer and director bothered to read the book.”

Ryckmans’ last book was a collection of essays in 2011, The Hall of Uselessness, discussing topics as wide-ranging as Don Quixote and Confucius. He also continued to write for the New York Review of Books, Le Figaro Littéraire, Le Monde and others. He was a fellow of the Australian Academy of Humanities and member of Belgium’s Académie Royale de Langue et de Littérature Française.

Pierre Ryckmans (Simon Leys), author and Sinologist: born Brussels 28 September 1935; married 1970 Han-fang Chang (four children); died Australia 11 August 2014.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments