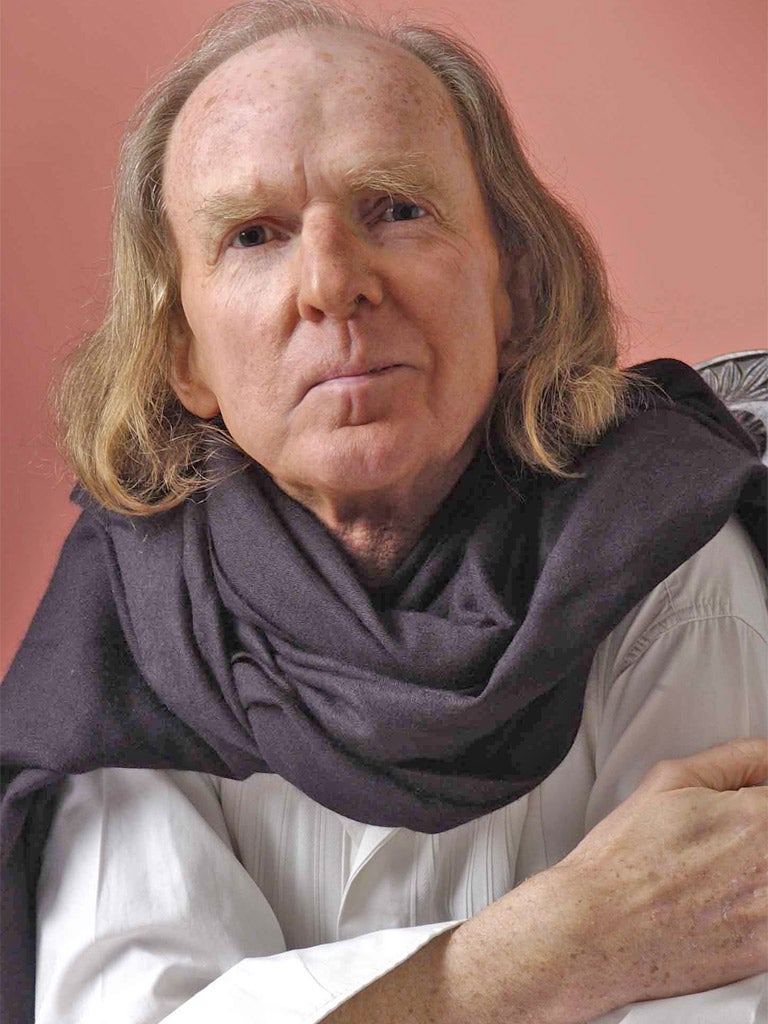

Sir John Tavener: Pioneer of ‘new’ classical music dies at the age of 69

The composer’s work breathed new life into the popular genre

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I’ll never forget the first time I heard the music of John Tavener, who has died at the age of 69. It was 1989: the world premiere of The Protecting Veil, his cello concerto, at the Proms. A sound began to emerge – one deep-set chord – and rose. And rose. And continued to rise, a shining, all-enveloping sound that sucked you in like a tunnel filling up with golden light. It confounded every expectation. Every time you thought it couldn’t carry on, it went further. It hit you in the gut, the heart and the human soul.

For decades it had been assumed – implicitly – that new classical music had to sound hideous, or it couldn’t possibly be any good. The effect of The Protecting Veil was akin to a glass cathedral appearing amid a Brutalist cityscape of stained concrete.

By then, of course, Tavener had been around for some time. His early works embraced the avant-garde. His breakthrough composition was The Whale, an oratorio based on the story of Jonah, first performed in 1968 at the London Sinfonietta’s inaugural concert and subsequently recorded on The Beatles’ Apple label.

His devotion to spirituality in music developed with his conversion in 1977 to the Russian Orthodox Church. There he seems to have found his true voice. Career landmarks from then on were numerous and high-profile.

His “Song for Athene” was played at the funeral of Diana, Princess of Wales, in 1997; his Blake-inspired “Eternity’s Sunrise” was dedicated to her memory. His Requiem was premiered in 2008 in Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral – but Tavener, who had Marfan syndrome and was continually dogged by ill-health, was too ill to attend. A heart attack in 2007 profoundly affected his approach to composition; among other things, he noted, his works emerged more concise. Instead of the vast scale of, for instance, his 2003 all-night vigil The Veil of the Temple, which lasted seven hours, he found himself confining his new pieces to a mere 20 minutes.

Cynicism inevitably attended Tavener’s success. His celebrity status, with many contacts in high society, show business and royalty, left some critics casting aspersions – quite unfairly – on the genuine nature of his art. Yet Tavener found a unique way to touch his listeners and to convey a message about the enduring spirituality of music.

At a time when the contemporary music scene was dominated on the one hand by enduring serialist complexity and on the other by the repetitive purling of American minimalism, Tavener’s music occupied a territory that became known, somewhat sneeringly, as “holy minimalism” – alongside that of the Estonian composer Arvo Part, and Henryk Gorecki’s Symphony of Sorrowful Songs. He proved that there was not only a place in the UK for new classical music that held wide audience appeal, but a positive hunger for it.

He remained a strong presence in public consciousness to the very end, his voice heard on Radio 4’s Start the Week on Monday (an interview was recorded on 31 October). His last work, Three Shakespeare Sonnets, is to be premiered on Friday in Southwark Cathedral.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments