How Guy Fawkes Day ruined my 'Baby Doc' Duvalier interview

When 'Baby Doc', who died earlier month, was in exile, the writer Ian Thomson sought out the bling-loving Haitian dictator for an interview. But things didn't go as planned...

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Jean-Claude "Baby Doc" Duvalier, the deposed playboy-President of Haiti, died earlier this month in the Haitian capital of Port-au-Prince, apparently of natural causes. He was 63. His father, François "Papa Doc" Duvalier, had appointed Jean-Claude President-for-life in 1971 at the age of only 19. Duvalier père entertained more than an anthropological interest in Afro-Caribbean ritual. His wardrobe of black suits and black homburgs lent him the aspect, Haitians say, of the Vodou divinity Baron Samedi, who haunts the graveyards in a top hat and tails like a ghoulish Groucho Marx.

Baby Doc was no less unusual a dictator. Having misruled Haiti for 15 years, he and his beautiful Haitian wife, Michèle Bennett, were overthrown in the popular uprising of February 1986 and fled, first to France, then to the United States. Their hurried departure overseas became the subject of Christopher Hope's entertaining 1989 novel, My Chocolate Redemeer, where a deposed Caribbean dictator commandeers two floors of a hotel in the South of France and expels any guests who stand in his large and dangerous way.

In 2011, out of the blue, Baby Doc returned to Haiti reportedly to help put his homeland back on its feet after the terrible earthquake of the previous year. In Port-au-Prince he was allowed to go about his business unmolested, but many Haitians suspected that he was back solely to reclaim funds ransacked from the state coffers. Some years ago, hoping to interview Baby Doc, I made my way to a hush-hush address in Queens, New York, where Duvalierist exiles had gathered to plot his restoration to power. It was the autumn of 2002. Dr Franz Bataille (who edited the pro-Duvalier newspaper Haiti Observateur) puffed importantly on a cigar while his girlfriend emerged from a back room with a plate of fried pork and a bottle of Haitian Barbancourt rum for us. In lachrymose tones, Dr Bataille spoke of the "golden years" of Haiti under Baby Doc and added tearfully: "Jean-Claude is an angel. Haitians would jump for joy to have him back."

Really? The Tontons Macoute private militia set up by his father in 1959 had caused tens of thousands to flee Haiti in terror. Moreover, the palace in Port-au-Prince where Baby Doc lived with his wife was a picture of excess. Spring-loaded security doors led to private apartments filled with giant artificial banana trees (fashioned from bamboo) with mirrored leaves and fronds, huge gold snails in the bathroom and great fluffy footballs behind Chinese vellum screens. In the presidential chapel a small projector screen hung above the altar: Baby Doc had a penchant for pornography in Technicolor.

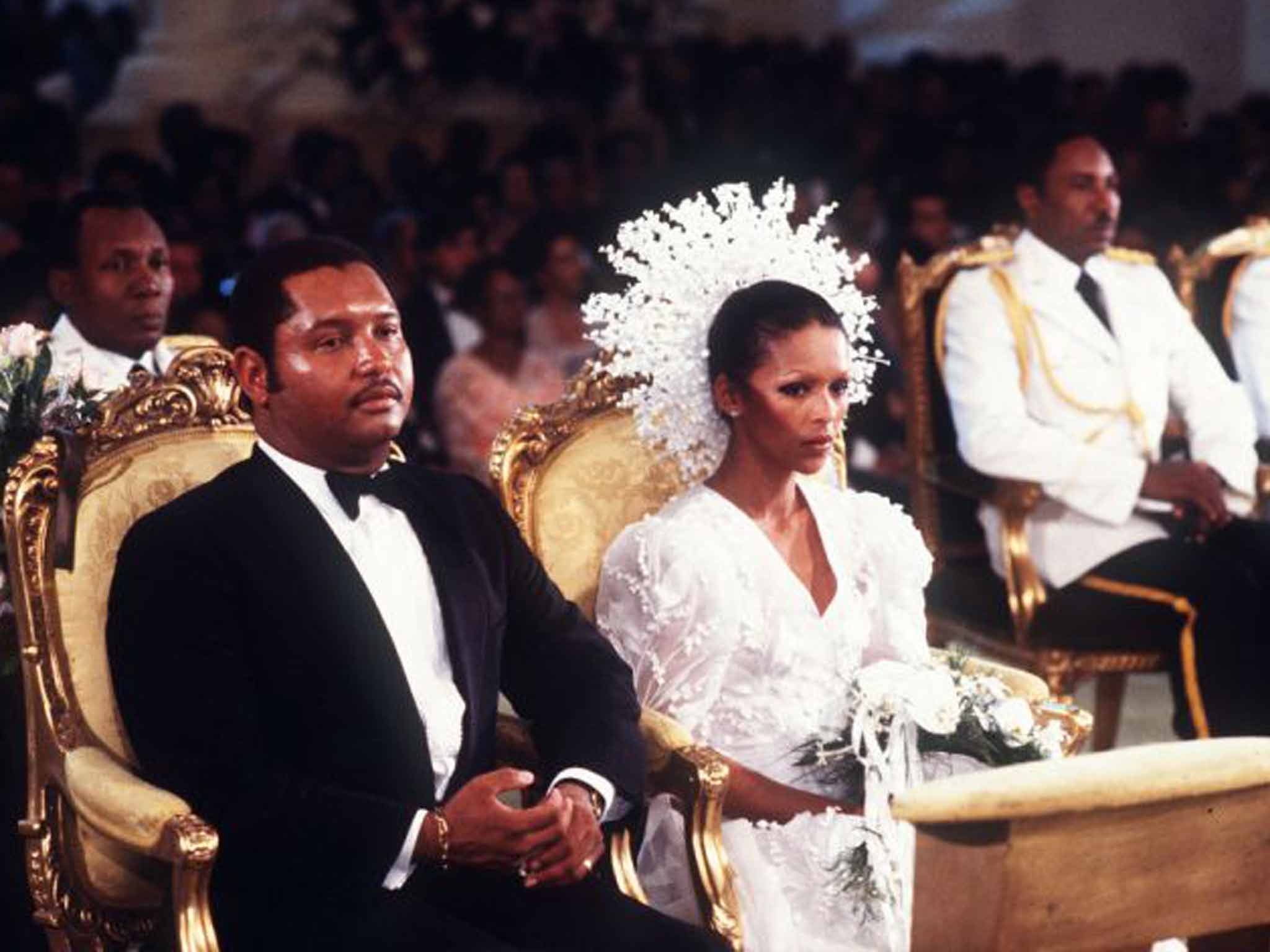

Proceeds for his wedding in 1980 derived largely from drug trafficking. Held in Port-au-Prince cathedral, it cost an estimated US $5m (£3m); couture gowns and hairdressers imported from Paris along with a $100,000 firework display ensured that the wedding made the Guinness World Records book for immoderation.

Unfortunately, festivities were marred somewhat by a torrential downpour that caused the city sewers to overflow.

With a sigh, Dr Bataille got up and dialled a long number. I watched as he bowed to the phone. "Bonjour Monsieur le Président, comment allez-vous?" (I could feel the tension in the room.) "Yes, we have Mr Thomson here. I'll pass him over to you." Taking the phone, I repeated Dr Bataille's fawning words to Baby Doc. "Good morning, Mr President. How are you?"

Baby Doc spoke so slowly in reply that I thought that he must be drugged or ill. (In fact, he was ailing from heart problems aggravated by diabetes.) After more suitably ingratiating remarks from me, the ex-dictator agreed to be interviewed for a newspaper article but asked me to contact him in his Paris exile once I had returned home. Back in Stoke Newington, I telephoned Baby Doc on 5 November, Guy Fawkes Day, which proved to be a mistake.

The instant Monsieur le Président picked up the phone, a neighbour let off fireworks beneath my window. There was a long silence as I struggled to speak above a background detonation of rockets. No reply was forthcoming. In increasingly strained French I tried to explain to Baby Doc the significance of the 1605 Gunpowder Plot. But Baby Doc wasn't listening any more. The phone went dead, and I never got the interview.

It is estimated that Baby Doc and Bennett embezzled between them some $200m to $500m. When proceedings to recover the money commenced in July 1986, the defendants claimed (plausibly enough) that it had been a tradition in Haiti for almost two centuries for a new government to take legal action against the previous regime.

Bennett, tired of living with the man Haitians nicknamed "Baskethead", divorced Baby Doc in 1990. The National Palace where the dictator and his wife had lavished minions with champagne and honorific titles was destroyed in the 2010 earthquake. Not even the giant artificial banana trees remain.

The new, post-earthquake edition of 'Bonjour Blanc: A Journey through Haiti', by Ian Thomson (Vintage), is published this week

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments