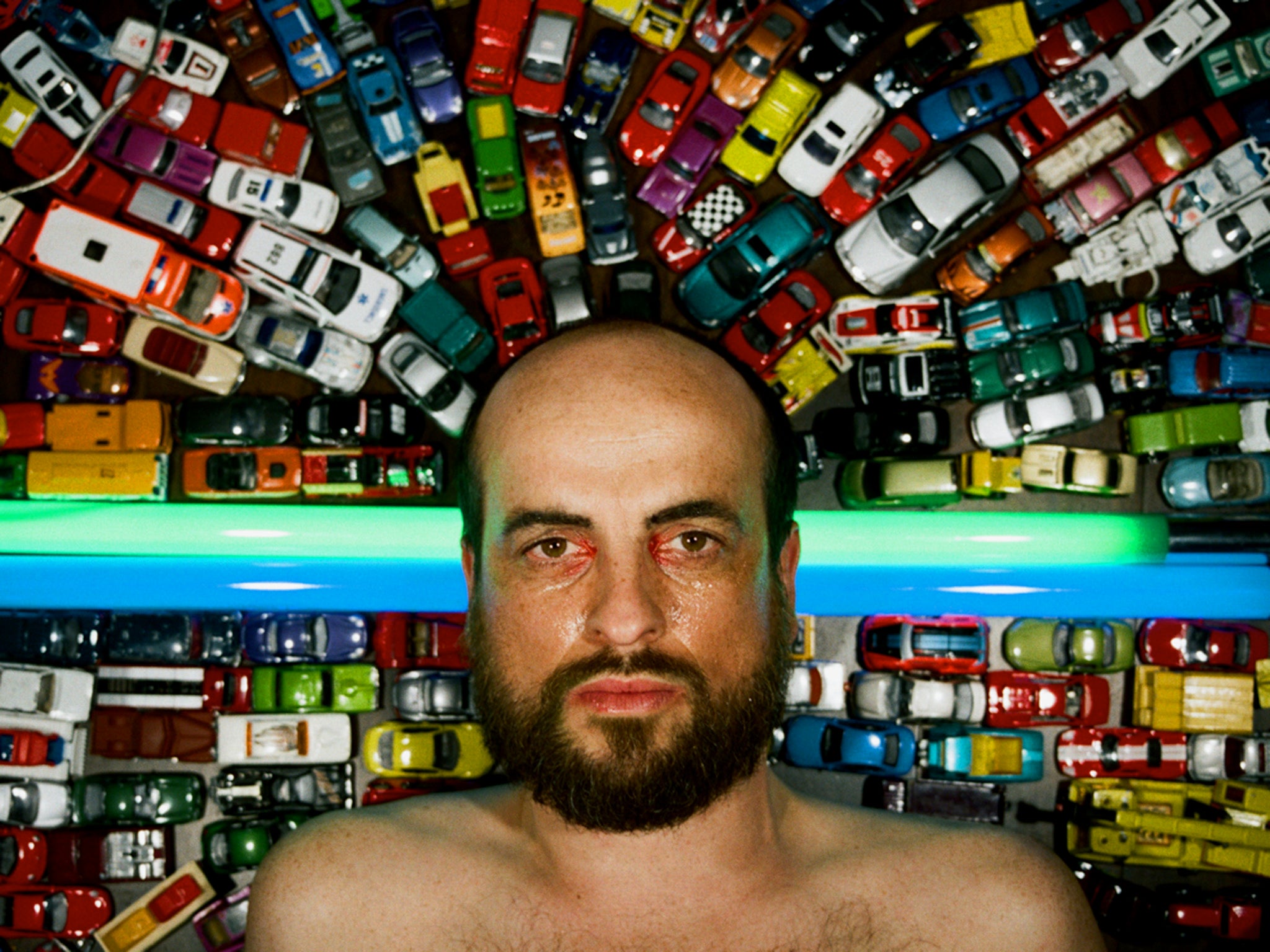

Musician Matthew Herbert on 'bringing down the government'

Pioneering electro musician Matthew Herbert has ambitions far beyond the creation of his next album

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Matthew Herbert’s children still struggle to understand what daddy does for a living, he tells me. The other day he was rattling a stick against the wall of his home in Whitstable, trying to disturb a mouse. His son looked up and asked: “What are you doing, Dad? Are you making music?”

It’s not surprising that his seven-year-old can’t fathom what he does when Herbert’s genre-defying projects involve rather a lot of musique concrète – using sampled natural sounds as the basis for his work, which confuses even his adult listeners – it’s definitely music but is it informative, or for fun? He’s probably the creator of some of the most inventive dance music that doesn’t get played in clubs and the most experimental jazz that you can still dance to.

Also known as Herbert, Doctor Rockit, Radio Boy and Mr Vertigo, Matthew Herbert has been making music for 25 years and made 30 albums, collaborating with all sorts of people, from Heston Blumenthal to Björk and remixing for Moloko, Dizzee Rascal, Ennio Morricone and REM.

We’re sat on a big, pink, comfy sofa in one of London’s private members’ clubs, discussing his new album, his philosophy of music and a lot of things that are wrong with capitalism. He talks slowly, thoughtfully, in a gentle cadence littered with “you knows” and rehashing of syntax; saying different iterations of the same sentence until he’s happy with the phrase. I imagine the production process for his music is similar, with each sampled sound moved around and manipulated until its in exactly the right place. Considering he can take three or four years to make one album, this is probably the case.

His new album, The Shakes, his first dance album since 2006’s Scale, is full of lively, arresting sounds. The Shakes is named after, “that moment that’s halfway between excitement and terror, because that’s what it feels like to be alive.”

“Battle”, the first track, starts with a background of almost military drumming and builds to a euphoric melding of chanting voices. “Safety” plays with discordant notes, abrupt pauses and disconcertingly warped vocals. There’s a satisfyingly bright, pinging beat that sounds like milk bottles being tapped together, or raindrops on porcelain. Who knows what that sound really is?

In Herbert’s albums any sound goes, from bombs to chickens dying. Scale includes the noise of a coffin lid closing, which underlies the whole album. “It sounds like a car revving, it’s one of the weirdest things,” he reflects. “What I liked about that though is it is a sound you would never hear unless you did climb into a coffin. Or if you were buried alive.”

Some audiences find his treatment of emotional subjects as sources of music disturbing. For the album One Pig, he recorded the life cycle of a farmed pig, to learn more about a process that most of us don’t see but rely on every day (pig-derived products are in everything from ink to dog treats to beer).

“I suddenly realised that I hadn’t spent any time with a pig my entire life,” he says. He was there at the pig’s birth and when it gave birth, but, “I wasn’t allowed to be at its death because of the arcane and ridiculous laws in this country that I’m not allowed to see what I put in my body.” He did, however, record the sound of the piglets being thrown against a metallic pen (“it almost sounded like a factory, again something I wasn’t expecting”) and the pig’s corpse being crushed. The album received criticism from animal-rights groups.

“There’s this whole moral responsibility there that musicians haven’t really had to answer before,” he says, also referencing The End of Silence, which is underpinned by a five-second audio clip of a bomb dropping in Libya, that he later discovered killed three people. “It’s a lonely thing as well, being sat in a corner of a studio with the sound of someone dying underneath your fingers. It’s something that war photographers and artists have thought about for a long time but it’s not something that musicians are used to.”

More recently he did a concert using recordings of the World Trade Center collapsing, at a two-day electronic music event in Geneva. When the collapse happened he had been staying in a hotel a couple of miles away and watched it from the rooftop.

“I thought I was going to die. It’s one of those things that’s awful when you’re in it... it felt like the world turned then, standing on the roof with America waking up to what it feels like to witness death on that kind of scale.” Several people walked out of the show. “People have quite an issue with it but my contention is, ‘what’s different between that and video footage?’... I’m not denying that there is a difference but I’m really curious, what is that difference?”

I suggest that people struggle to categorise his work neatly and assume he’s trying to make the sound into music for entertainment.

“People always assume that music is entertainment and that’s not always been the way,” he gently counters. “I think it can be a million things. I mean, that little piece of music that tells you your phone’s ringing serves a very different purpose to Wagner’s Ring cycle... All music is telling you: ‘Hey guys! Don’t worry, everything’s OK!’... at a point when we’re living in a system that’s destroying everything we lean on. That’s an incredibly powerfully toxic world view. So I think it’s terribly important to have something to prick the bubble.” Herbert’s raison d’être seems to be to remind us that everything is not OK. The motif of connection, or lack of it permeates his work and his world view.

The Shakes started off as a celebration of time spent with his family again after a busy year spent working on large projects with the National Theatre and the Berlin Opera House. When he returned home he began to relax, “and then Israel started bombing Gaza and the number of children that were killed was just so disturbing... So it starts out with quite a spring in its step and then it gradually sort of, not decays, but it composts or something. It was so at odds with the experience I was having with my own family in the summer, living in this seaside town in Britain, making music.” He says it almost contemptuously, with full recognition of the privilege inherent in the words. “And the world, you know.” He’s momentarily lost in the vastness of the concept; that disconnection between his luxurious life and what’s happening simultaneously over in another part of the planet.

In order to make things right, Herbert is launching a new, virtual, country, called CountryX (www.countryx.org) which he’ll discuss at FutureFest, an event that attempts to offer insights on our future, held at Vinopolis in London this weekend. CountryX is for like-minded individuals to come together and claim citizenship.

“Some of the best bits about being British are things like Brixton market – things which so many people consider unBritish,” he says. “The clash and friction and love in between different cultures – and it seems absurd that Britain should be defined by its geographical location. We are treated as international citizens anyway by companies.” He gestures towards his MacBook. “We’re under the United States of Apple now, you know?”

CountryX is an experiment he aborted in 2006 because there was no-one to handle its sudden popularity, when he was overwhelmed with emails claiming asylum and offers to be part of the country’s government. “One person called up and offered to be the minister that says yes, which I thought was brilliant,” he says.

This time round, he’s hoping to, “bring down the Government, change the capitalist system, bring peace.” He’s partly joking but what he does believe is with enough people, real, visible change might take place. The plan is to get one million people signed up before deciding specific actions to take because “it’s much easier to enact serious and profound change when you’ve got numbers and momentum.” I ask whether he agrees with Russell Brand that the only sane response to a useless government is to stop voting.

“I think it’s a disaster, actually. I love the fact that he’s agitating and that someone’s speaking about the subjects he’s speaking about... but not voting is a vote for the status quo or a gift to the right.” While CountryX is still in the embryonic stages, he’ll continue to make provocative music, recording sounds you don’t encounter every day, and hoping they’ll have an impact.

“That’s what really interests me about sound,” he says. “It can get you places you’ve never been before. It can get you in the dark. Sound goes round corners and through the dark – and that’s exciting.”

Matthew Herbert speaks at FutureFest on 14 March (futurefest.org) and plays Village Underground in London on 17 March. ‘The Shakes’ is out 1 June

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments