Meet Willie Morgan – the man who grows cotton in Harlem to teach kids about slavery

The 78-year-old has lived in the iconic New York neighbourhood since 1969

The soil in Willie Morgan’s Harlem gardening plot is nothing compared to that back home in his native Georgia.

But it is fertile enough for him to grow more than a dozen vegetables – collard greens and okra, onions and stevia. To one side, he even has a peach tree that in the summer produces blindingly sweet fruit.

Every year, the 78-year-old also grows something with a much darker, troubling history – cotton. He does so to teach local children about a fundamental part of American history, the effects of which still ache like an open wound.

“I tell the kids about, tell them that the jeans they’re wearing come from cotton. They don’t know anything about it,” he said. “I give them the cotton and they can take it into their classes.”

He added: “This is what slavery was about. They did not have machines. They needed people to pick it…[That way] they know about the cotton, they know what their forefathers did.”

The first slaves, seized from Africa, were brought to the new English colony of Jamestown, Virginia, in 1619. At the time of the US Civil War, for which the South’s desire to maintain slavery was a major trigger, there were four million slaves.

The legacy of this wholesale bondage has continued to shake and shape America’s history, from reconstruction through the civil rights movement. The recent documentary,13th, has explored how the nation’s criminal justice system, in which people of colour are disproportionately imprisoned, has its genesis in the formal ending of slavery.

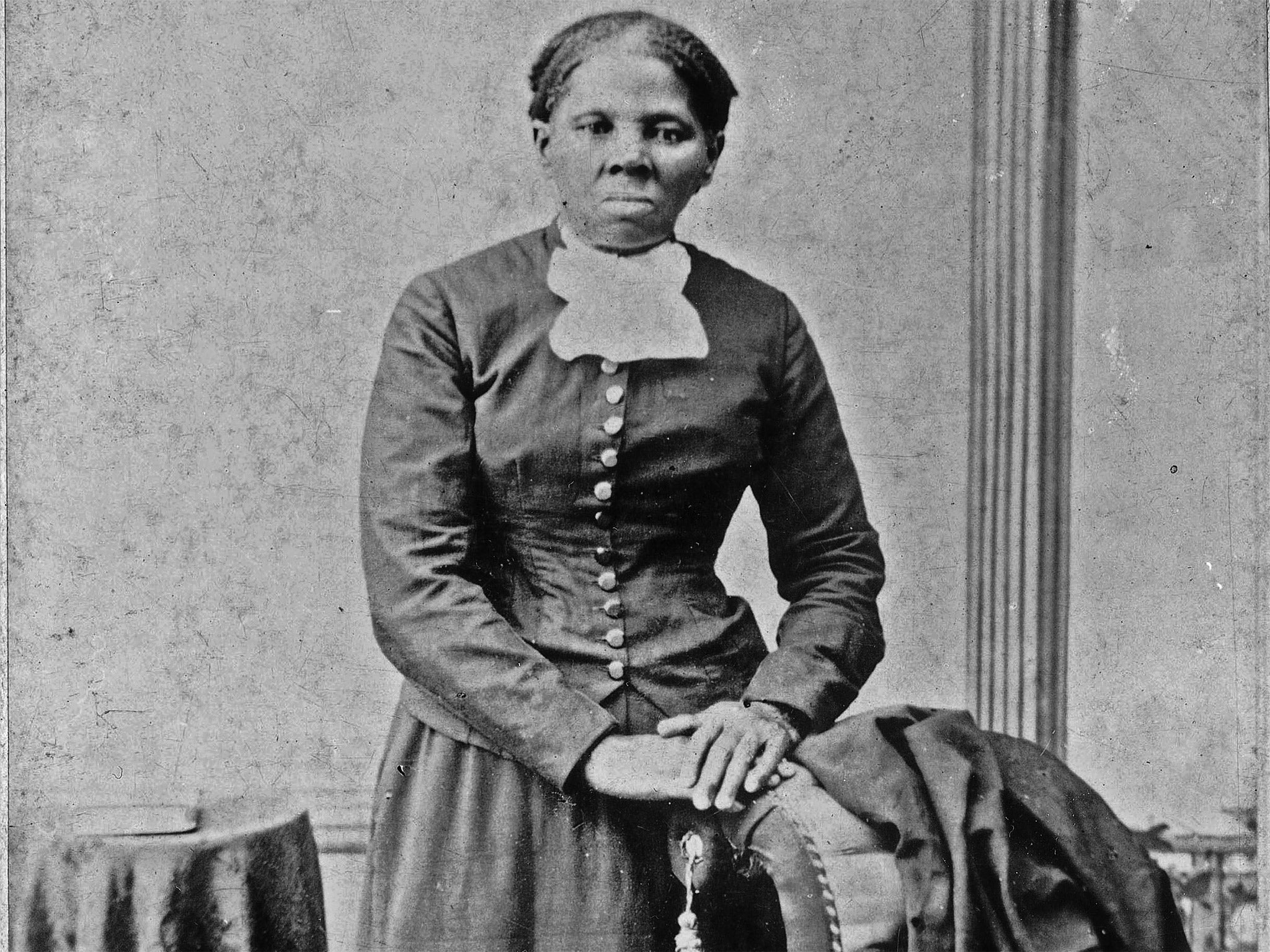

Mr Morgan, whose enthusiasm and vigour belies his years, began planting his cotton plants, which ripen in September and October, 11 years ago, a year before a statue of Harriet Tubman, the famed campaigner and slave abolitionist, was erected at the junction of 122nd Street and Frederick Douglass Boulevard, near his garden plot.

He plants the seeds in June, always soaking them in water the evening before he puts them in the ground, for them to grow faster.

Now, in addition to keeping an eye on the cotton, and the peanuts which he also grows there, Mr Morgan acts as an unofficial guide to tourists who come to take pictures of the statue. Earlier this year, the US Treasury announced that Tubman will replace Andrew Jackson, the seventh president, on the $20 bill, following a public campaign to have a woman on the nation’s currency.

Mr Morgan has lived in Harlem, which has historically been America’s most iconic black neighourhood, since 1969. He has seen it through decades of crime, drug addiction, white flight and rebirth. In more recent years, the neighbourhood has gentrified, a change that remains controversial.

“Oh, has Harlem changed,” said Mr Morgan, who is divorced and has two children. “The jobs went, and the economy went down in the 1960s and 1970s. There were heavy drugs.”

Over the years, he has worked in the garment industry in Manhattan, managed a bar, run a clothing boutique on 125th Street named Bodacious Unlimited, and run an illegal numbers game.

Throughout that time, he has kept growing vegetables and fruit for himself and others. He currently has six customers who live in the apartment blocks that look down on his patch.

“We have more than 500 such community gardens,” said Crystal Howard, a spokeswoman for the New York City parks department. The city’s scheme GreenThumb is said to be the biggest community gardening programme in the country.

Mr Morgan was featured in the book Eat the City: A Tale of the Fishers, Foragers, Butchers, Farmers, Poultry Minders, Sugar Refiners, Cane Cutters, Beekeepers, Winemakers, and Brewers Who Built New York.

Author Robin Schulman said Mr Morgan was part of a history that had seen people make use of abandoned land to grow their own food, something Mr Morgan's family had done in the south. She told The Independent: “I think the lesson is, that however unusual it may seem, you can create part of who you are in the most unlikely places.”

Mr Morgan said one of the impacts of white flight from Harlem was that the cost of property tumbled. His parents had been fortunate to buy their own home.

Now, as Harlem confronts both the benefits and downsides of gentrification, the cost of renting or buying a property is reaching very high levels, forcing out many people who have lived here for decades.

“The prices are going up,” he said. “They are putting up more buildings than ever.”

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks