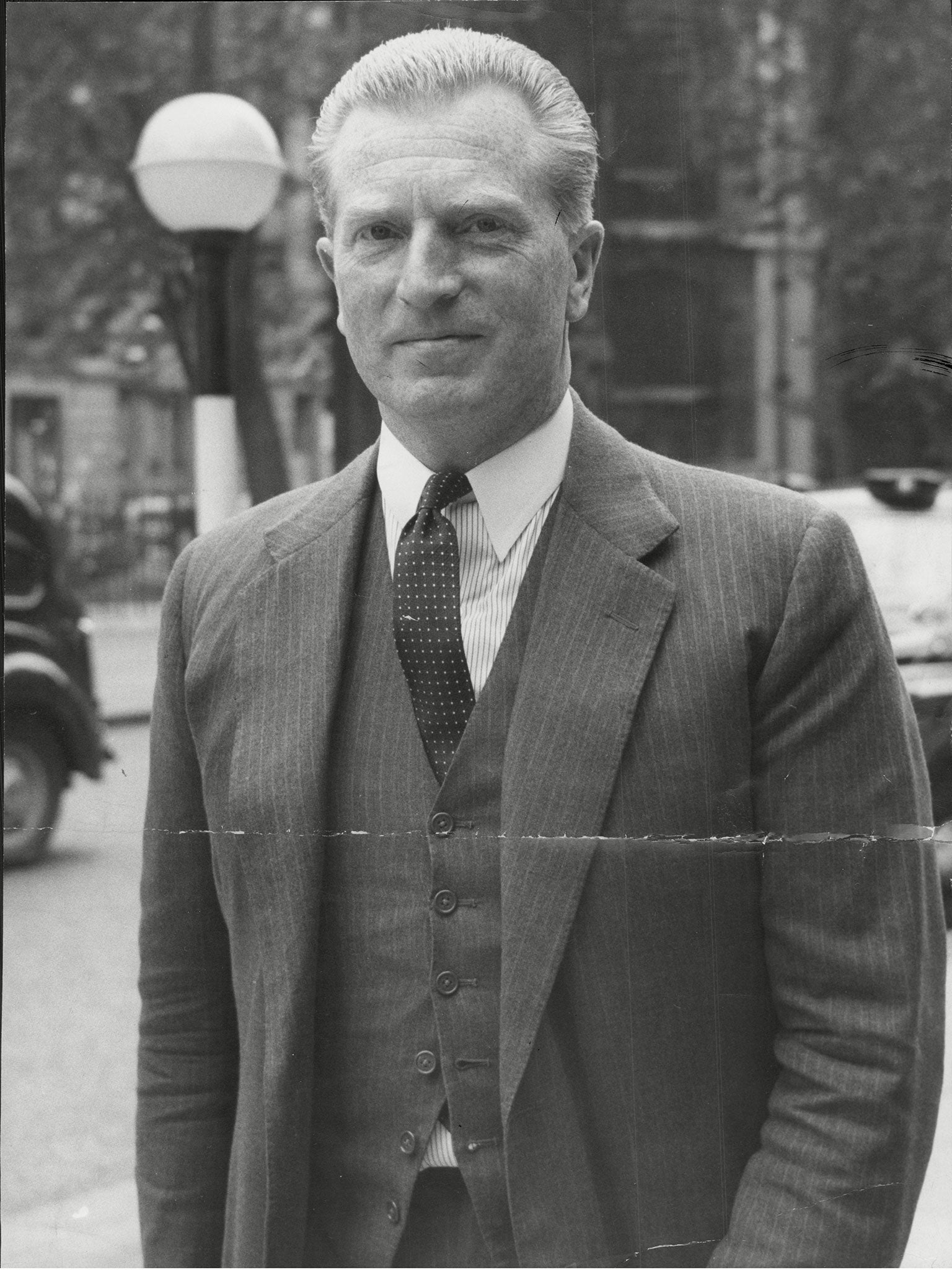

Major John Freeman: Soldier who became an MP, diplomat and broadcaster best known for his series of interviews, Face to Face

He left Edna O’Brien, telling her, 'I don’t think I could be in love with anyone'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.On 16 August 1945, the day after the official end of the Second World War, Parliament met for the first time following the Labour Party’s landslide victory in the General Election. It was widely understood that the votes of servicemen had been the key factor in Labour’s triumph and Major John Freeman, representing Watford, was one of several new MPs who arrived at the House of Commons in their military uniforms.

He had been chosen to move the Motion on the Address. "This is D-Day for the New Britain," he declared resoundingly; and in some respects it was, although many of the high hopes that he and his fellow socialists entertained for the postwar era would inevitably be dashed. None the less, it was certainly the day that marked the start of the tall, red-headed 30-year-old major’s eclectic and high-flying career as a politician, journalist, diplomat and media executive. Winston Churchill, still adjusting to the unfamiliar role of Leader of the Opposition, predicted that he had an important political career ahead of him, and growled: "They now have all the best young men on their side." Freeman would, in, time, become the last surviving member of the 1945 Parliament.

Born in north London in 1915, he was the son of Horace Freeman, a successful barrister in Chancery. He had a difficult and solitary childhood. By his own account his parents were incapable of showing him overt affection and he was left much to his own devices. Early on he developed a streak of independence and a frigid and lofty personal manner that would stay with him throughout his life. It was particularly marked in Face to Face, the chilling but greatly revealing series of television interviews that he conducted for the BBC between 1959 and 1962. Tom Driberg, a long-time friend, noted his "extreme reluctance to bare his soul, to wallow emotionally in public".

He was sent to Westminster School as a weekly boarder, though he could easily have commuted from the family home in Brondesbury. As head of house there he suspended the long-standing practice of prefects meting out corporal punishment. This was an early symptom of his egalitarianism, fortified when he attended political meetings addressed by the likes of the radical Stafford Cripps, the feminist reformer Ellen Wilkinson and the Indian socialist Krishna Menon.

At Brasenose College, Oxford, he temporarily abandoned such earnest concerns and opted for a sybaritic three years of wine (he was a lifelong oenophile), women and fast cars. That last enthusiasm nearly proved fatal when, in his second undergraduate year, he fractured his skull in a road accident. The result was that he left Oxford with only a third-class degree in Greats and took a job in advertising.

In 1938 he married Elizabeth Johnston, but later admitted that, at 23, he had not been mature enough to make a lasting commitment. The enforced separation of the war years proved a mortal blow to the marriage and they were divorced in 1948, freeing him to marry Ista Kerr (known as Mima to her friends).

When war was declared in 1939 he enlisted as a guardsman and was soon commissioned in the Rifle Brigade, playing an active role in the north African campaign. Field-Marshal Montgomery called him the best brigade major in the Eighth Army. His interest in politics had by now been rekindled and he allowed his name to be put forward for the Watford constituency in the 1945 election, although it had until then been a safe Conservative seat and he did not expect to win.

As soon as he entered Parliament he was singled out as a potential minister, being given a series of junior posts in the War Office until, in 1947 he was appointed Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Supply. Impressive performances at the despatch box confirmed Churchill’s view that here was a politician of great promise. Yet the postwar Labour Government, after its initial burst of enthusiasm and achievement, was becoming increasingly schismatic, with a left-wing faction forming around Aneurin Bevan, the Minister of Health. Freeman aligned himself with the Bevanites and became a friend and ally of Driberg, an outspoken left-winger. When Driberg married Ena Binfield in June 1951 – a surprising move, since he was a flagrant homosexual – Freeman was his best man.

By that time he was out of the Government. A few weeks earlier, when Bevan resigned, Freeman and Harold Wilson, the President of the Board of Trade, quit in solidarity. The immediate trigger for their action was the imposition of prescription charges in the National Health Service, but Freeman was equally exercised about the amount of money being spent on the armed forces at the expense of the social services. Clement Attlee, the Prime Minister, sought to persuade him to stay on, offering him Wilson’s berth at the Board of Trade, but he refused to change his mind.

His resignation was not as much of a sacrifice as it might have appeared. For one thing, he was becoming disillusioned with Parliament and its self-serving intrigues; and for another he already had a job to go to. A few months earlier he had been approached by Kingsley Martin, who had been editing the New Statesman for 20 years and had established it as the most important weekly political journal in the country, a significant outlet for left-wing thinking. Although still only 54, Martin recognised that at some stage he would have to hand over the reins, and began looking for a successor.

Freeman’s journalistic experience consisted only of a term as editor of Cherwell, the Oxford student newspaper. None the less he accepted the role of assistant editor of the New Statesman and gave up his Commons seat in 1955. Later he became Martin’s official deputy and heir apparent, dashing the hopes of Richard Crossman, the future Cabinet Minister, who had set his heart on the editorship. (When Crossman eventually did edit the journal, some 20 years later, he was notably unsuccessful.)

An advantage of working for the New Statesman was that it kept Freeman in the public eye after his resignation while allowing him the time to develop a new skill as a television performer. He was offered work by the BBC, first as a freelance current affairs reporter on Panorama, then on Press Conference, a political discussion programme. On Panorama he conducted a merciless interview with Frank Foulkes, the Communist President of the Electrical Trades Union, who had been accused of rigging the union ballot.

Cross-examination was his forte – a skill he may have acquired from his father. It reached its flowering in Face to Face, a series that began in 1959. Until then, there had been few instances of the hard-hitting, confrontational TV interview. Public figures were given a fairly easy ride by broadcasters, with any hint of potential embarrassment scrupulously avoided.

Freeman recognised that provocation would generally draw out more truth from interviewees than politeness. Sitting with the back of his head towards the camera, and with the victim’s face in close-up, he turned the programmes into gladiatorial contests. In an unemotional, forensic style, he would nag away at any weaknesses he perceived in his subjects’ defences. In one notorious programme, the game show panellist Gilbert Harding was reduced to tears during a relentless interrogation about his family history. The series was immensely popular and in 1960 Freeman was named television personality of the year.

His formidably intimidating public persona did not mean, though, that he was devoid of passion and human frailties. He was attractive to women. Ista died in 1957 and a year later he met Catherine Dove, his producer on Press Conference. Although Dove had only recently married Charles Wheeler, a well-known BBC reporter, she and Freeman immediately fell in love. They married in 1962 and had three children.

His several affairs included one with the novelist Edna O’Brien, who wrote a fictional but recognisable account of their initial mutual obsession and its painful ending in a moving short story, The Love Object, published in 1968. She dwelt on his cool precision – asking for a brush to remove a speck of powder from his suit before taking his leave in the morning – and described the collected way in which he eventually ended things: "I adore you but I’m not in love with you, with my commitments I don’t think I could be in love with anyone."

Although the success of Face to Face meant that he could easily have made a career in television, Freeman stayed with the New Statesman and in 1961 took over the editor’s chair formally. He felt that the journal had been drifting into complacency during Martin’s last years at the helm and did his best to sharpen it up and to bring in younger contributors and readers. In doing so he exercised the same ruthlessness that made him such a compelling inquisitor.

One of his first acts was to fire his friend Tom Driberg, the magazine’s television critic, although he knew that Driberg was in dire financial straits. Even Kingsley Martin, who had been given a roving commission after vacating the editorial chair, found it hard to get everything he wrote into print.

After four years as editor, when Freeman was beginning to feel that he had done as much for the magazine as he could, a new chance to broaden his career presented itself. In 1964 Harold Wilson had led the Labour Party into power after 13 years in opposition, and one of the ways in which he sought to signal the spirit of his administration was by making imaginative appointments to key diplomatic posts abroad. Freeman was invited to become High Commissioner in New Delhi. He took little persuasion, and arrived there in 1965.

The toughest period of his four-year assignment came during the war between India and Pakistan, quarrelling over the borders that Britain had drawn for them. Yet although he could never communicate fruitfully with Indira Gandhi, who became Prime Minister of India in 1966, his period there was deemed such a success that in 1969 he was given the plum posting of ambassador in Washington, where he forged an improbably cordial relationship with President Nixon.

He had been in the US capital for not much more than a year when the Conservatives won the 1970 General Election. Such was his stature by then that the new Prime Minister, Edward Heath, asked him to stay on, despite his Labour Party roots. He refused, not out of any political loyalty but because he had already been offered a position that would take him into yet another high-profile field of activity.

In 1966, when the London Weekend Television consortium was formed to bid for the lucrative ITV franchise, he had been invited by David Frost, one of the prime movers, to join it. Only a year into his post in India he felt unable to accept; but he said that if they still wanted him when his diplomatic stint was over, he would be happy to consider it.

LWT won the franchise and initially hit all kinds of trouble, both financially and creatively. In 1970 Rupert Murdoch, who had in the previous two years established his British press empire by acquiring the News of the World and The Sun, bought a substantial block of shares in the ailing TV company, making him the largest shareholder. However, because of rules preventing cross-ownership of newspapers and TV stations he was unable to exercise executive control. He sought a chairman, and Frost suggested approaching Freeman in Washington.

After meeting Murdoch, the ambassador agreed to the proposal. The two men admired each other. Freeman’s left-wing political views had gradually been eroded until he found himself broadly sympathetic to the Australian’s entrepreneurial free-market philosophy.

When I interviewed Freeman for my 1982 biography of Murdoch he said the atmosphere when he arrived at LWT was like a casualty clearing station after a major battle. Many senior executives had been fired, and not all had been replaced. Morale was low and nobody was confident that the company had a future. He immediately exercised a calming influence and led LWT into its most fertile decade, when it nurtured such talents as Michael Grade, John Birt, Melvyn Bragg and Greg Dyke.

His personal life had gone through another upheaval. In 1971, a few weeks after departing from Washington, he shocked Catherine by telling her that he was leaving her and their young children to set up house with Judith Mitchell, a South African who had been Catherine’s social secretary at the Washington embassy. It was a rancorous split, with the divorce not finalised until 1976, when Freeman and Mitchell married. They had two daughters.

He quickly earned a reputation as one of the most effective executives in television. He was chosen as chairman of the council of the Independent Television Companies Association from 1974 to 1975, vice-president of the Royal Television Society from 1975 to 1985, a governor of the British Film Institute from 1976 to 1982 and chairman of Independent Television News from 1976 to 1981. During his career he was offered both a knighthood and a peerage but turned them down. Having experienced the frustrations of the House of Commons all those years earlier, he did not relish the prospect of serving time in the Lords.

In 1984, at the age of 69, he stepped down from LWT and from most of his other positions, although for some years he was a visiting professor in international relations at the University of California in Davis. He took up bowls – a game that ideally suited his calm, calculating mind – and became champion of the south of England. In the last years of his life he was afflicted with cancer but, while he shunned the limelight, he retained a lively mind and kept in contact with his closest friends. In 2012 he moved himself to a military nursing home in south London so as not to be a burden on his family.

John Freeman, soldier, politician, journalist, broadcaster, diplomat and media executive: born London 19 February 1915; MP for Watford 1954-55; MBE 1943; married 1938 Elizabeth Johnston (divorced 1948), 1948 Ista Kerr (died 1957), 1962 Catherine Dove (divorced 1976; three children), 1976 Judith Mitchell (two daughters); died 20 December 2014.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments