John Daniel: Anti-apartheid activist who spent years in exile and went on work for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Fifty years ago John Daniel and his fellow student leaders had the wild idea of inviting Robert Kennedy to South Africa. At the time, most public opposition to apartheid had been silenced and one of the few organisations able to speak out was the National Union of South African Students (Nusas).

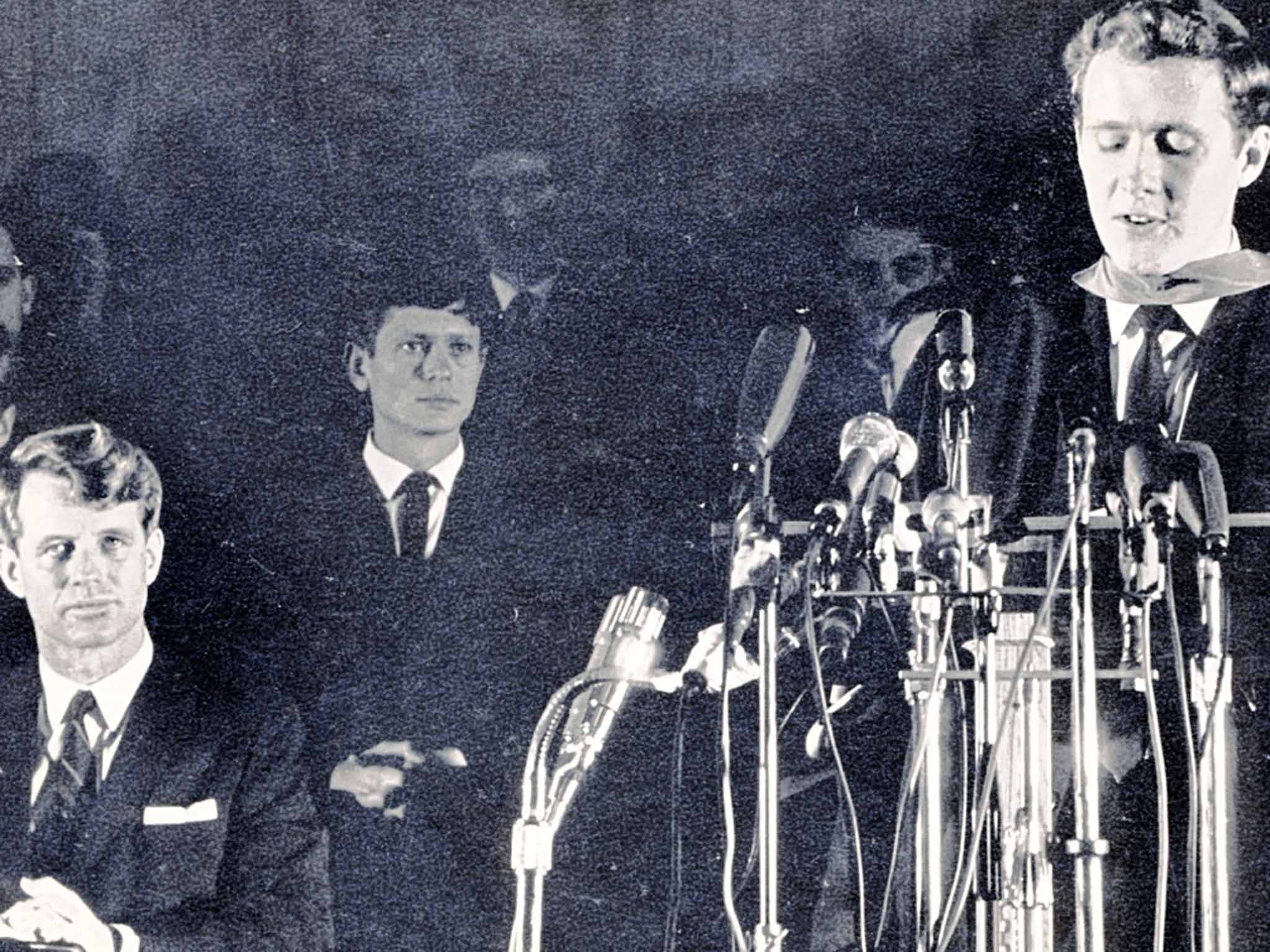

To everyone's surprise, Kennedy accepted their invitation and delivered what is often described as an "electrifying" speech at the University of Cape Town in 1966. But some of the students were even more impressed by the militant oration that followed, given by John Daniel, who had travelled with Kennedy as part of his entourage.

Four years earlier Daniel had arrived at the University of Natal as an ambitious, privately schooled 17-year-old with the conservative political outlook of his English immigrant parents. But his experiences writing for the student newspaper and working with black students radicalised him, and he went on to serve two terms as Nusas president.

After the Kennedy speech, he became a hate figure for the state, and in 1968, facing a "banning" order, he began 23 peripatetic years in exile, starting with a seven-year spell in the US, where he studied history under the novelist JM Coetzee before completing his PhD at the State University of New York.

At the first opportunity he found a way of returning as close as he could get to his homeland, taking an academic post at the University College of Swaziland, while also heading the country's committee for South African refugees and working with the Geneva-based World University Service, which funded anti-apartheid organisations.

Daniel would go on to describe his Swaziland years as his "most exciting and politically engaged". He was a member of the banned African National Congress, a non-communist leftist and an energetic activist, but his students and colleagues viewed him as the antithesis of the doctrinaire ideologue – and he steered clear of the kind of esoteric Marxist theory fashionable in the European left at the time.

Instead he was known as a drinking man with a penchant for politically incorrect jokes, a passion for Liverpool FC and a fiercely competitive streak which emerged most strongly on the squash court. He was also a prolific writer, and an exuberant and engaging lecturer. A colleague in Swaziland, Roger Southall, described him as "warm, passionate, optimistic, critical, enthusiastic, open and friendly" and said he was "also something of a raconteur, which is a polite way of saying he thoroughly enjoyed gossip, and indeed whenever I wanted to impart something of importance to the nation I broadcast it through Radio Daniel."

Another friend, Dan O'Meara, described how Daniel coped with the dangers of living in Swaziland at the time: "His life was overshadowed by the brutal interventions of apartheid forces across Southern Africa, by the trauma of frequent murders of close friends and comrades, by the exigencies of clandestine politics and the knowledge that anyone could be a target. Yet in this fraught and increasingly paranoid environment he exuded a joie de vivre which I have never forgotten."

The Swaziland government banned the ANC in 1975, and Daniel was expelled. He spent a year lecturing in Amsterdam before moving to London to become senior editor at the radical publisher, Zed Books. He headed their African division for five years, making sure that political affiliation didn't figure in the titles he chose, and he had a reputation for choosing controversial books that attracted a wider readership.

When the ANC was unbanned Daniel could finally return home, and he took up a senior lectureship at Rhodes University before being appointed professor of political science at the University of Durban, Westville in 1993.

Four years later he was appointed to head research for the country's Truth and Reconciliation Commission, a job he would describe as "the most challenging and important of my life". He criss-crossed the country, taking testimonies from victims of apartheid violence of the previous decades, and wrote substantial sections of the TRC's final report, including its findings and conclusion section.

He was then snapped up by South Africa's Human Sciences Research Council for the dual role of directing their research on government and democracy and reviving the moribund HSRC Press, which he transformed into a major academic publisher. Perhaps its most important publication during his term there was its influential four-volume State of the Nation series, which he co-edited and contributed to.

After compulsory retirement in 2006 he emerged as director of the South African division of the School for International Training in Durban, retiring again five years later. Soon afterwards, he was diagnosed with cancer but he continued to write and lecture. Shortly before his death one of his papers, on transitional justice, was presented at a seminar at Oxford University, and Skype was employed to engage Daniels in a lively question-and-answer session afterwards.

Janet Cherry, Professor of Politics at Port Elizabeth's Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, worked closely with Daniel over the last 20 years of his life. "One of my strongest memories is of sitting with him in an airport lounge, waiting for our flights, talking through the pain of the cases he researched; him recounting cases from KwaZulu-Natal that were so hard to talk about. We were both crying, and it was the moment when I realised what a profoundly compassionate person he was – a warm, egalitarian humanist who was also sharply critical and incisive, and he never pulled rank."

John Daniel, academic, editor and activist: born Pietermaritzburg, South Africa 3 March 1944; married firstly Judy Andrews (divorced; one daughter), secondly Cathy Connolly (one son, one daughter); died Durban 25 July 2014.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments