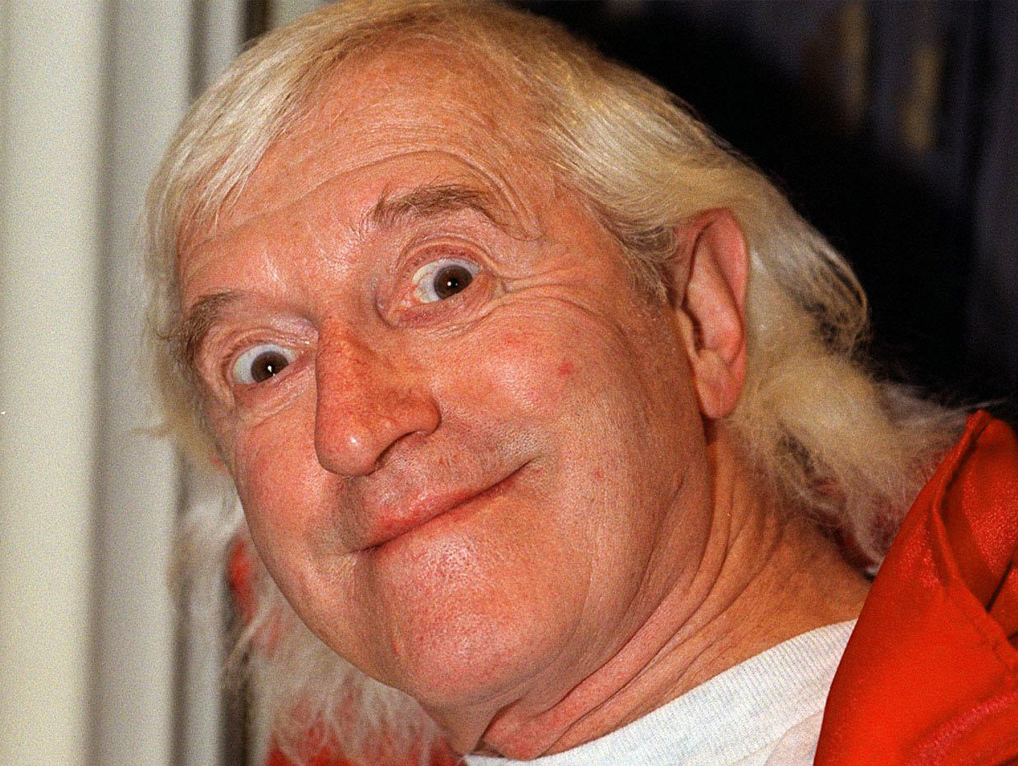

Jimmy Savile admitted getting knighthood was 'a relief because it got me off the hook'

In light of the new Louis Theroux documentary on the disgraced broadcaster, this compelling and disquieting interview by the celebrated journalist Lynn Barber takes on new meaning. It was first published in 1990 in The Independent on Sunday

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Sir James Savile is absolutely knocked out, over the moon, tickled pink, and thrilled to bits with his knighthood, and still reeling from the excitement of it all. Ooh, but it has played merry hell with his diary. “The Queen deciding to give me this tremendous responsibility – I mean, you go to bed one minute without a care in the world and you wake up the next morning with this gi-normous responsibility come through the letterbox.

Do you want to see the gear?” he asks, burrowing under the put-u-up to find his briefcase (we are in his London flat) from which he produces a transparent plastic folder. “Read it all,” he urges. “Go on. Have a little dwell on that. That folder encapsulates it all.”

The folder encloses the letter from the Prime Minister offering him a knighthood, the envelope it came in, some bumf about keeping it secret till the proper date and then – proudest of all – telegrams from Charles and Diana, from Prince Philip, a handwritten letter from Angus Ogilvy and a very sweet homemade card with a stuck-on snapshot of Princess Bea, from the Duchess of York. He is almost bursting with pride as he shows them off.

“I was lying in bed here,” he recalls, “when I heard the little clink on the door and an hour later, when I got up, I picked up the letter – there was only one letter on the floor – and it said ‘OHMS’, so I thought it was from the Income Tax. And I thought, ‘That’s unusual’ – because I get my tax stuff up in Leeds. But what I got was: ‘OHMS. Urgent. Personal. From the Prime Minister’s Office’ – and there it was.”

The letter from Downing Street encloses a form which he had to sign to say he would accept the knighthood, and, rather than trust it to the post, he hopped in a taxi and delivered it himself to the policeman at the end of Downing Street. The policeman said “Congratulations”, but Jimmy (he was still Jimmy in those days) said, “I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

He didn’t tell a soul. It was “36 days of agony” between hearing of his knighthood and its public announcement. “Ooh, I can’t tell you the agony, because the ramifications of not telling were just phenomenal. People would say, ‘Now next week...’ and I’d go, ‘Hm?’ For the first time in my life, I appeared to be indecisive, because I’m always totally positive.

Video: Savile had 'unrestricted hospital access'

“And all my people, at Leeds Infirmary, at Broadmoor, Stoke Mandeville, were all ringing each other up saying ‘Here. What’s wrong with the Godfather?’ They thought I was sickening for something. The last 48 hours were the worst – grind, grind, grind. When it came out at midnight – radio and teletext at the same time – it was such a relief.”

Since then, he has had 900 letters, 700 phone calls of congratulations, and he promises he will reply to them all in the fullness of time when he has recovered from his daze.

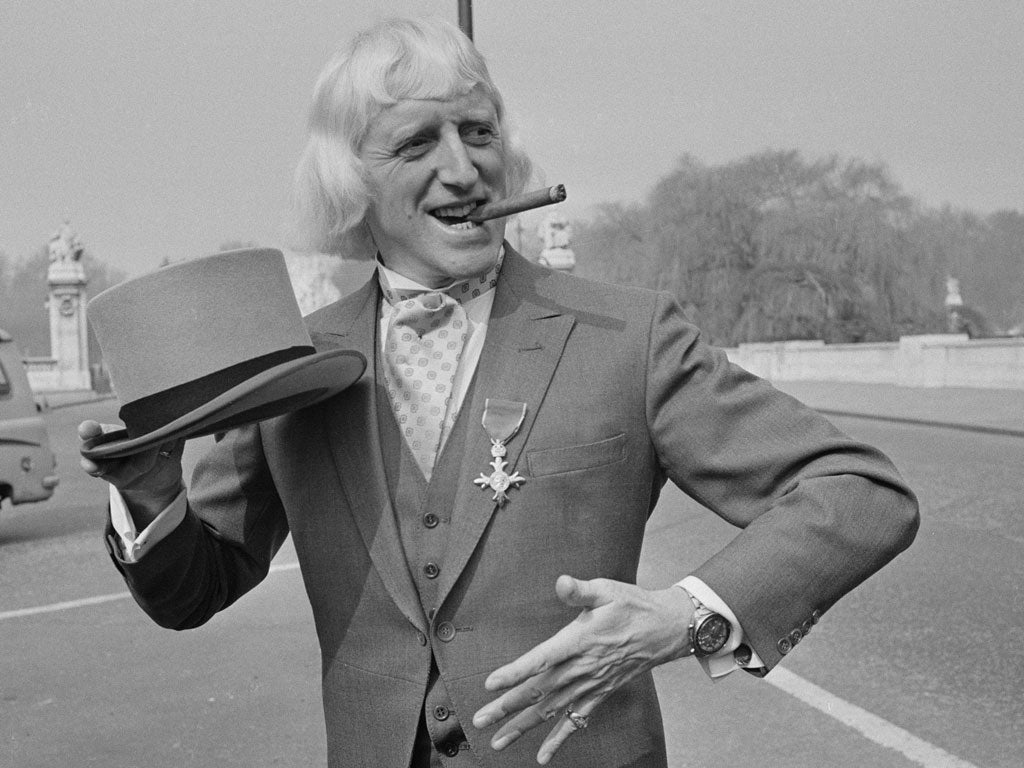

He is still undecided whether he wants to be Sir James or Sir Jimmy, and looks at me a bit carefully (“Is she taking the mickey?”) when I call him “Sir James”. But he certainly wants to be called one or the other; he is intensely proud of his honour. Alone among television stars, he has always insisted on having his OBE after his name on the programme credits.

The only surprising thing about his knighthood is how long it has taken him to get it. He has been raising money for charity for at least 20 years – more than £30m at last count – and Stoke Mandeville’s National Spinal Injuries Centre is almost entirely a result of his efforts. The day after I met him, he was going to open yet another £2m donation to the hospital – a new magnetic resonance imager which for the first time will enable surgeons to see the spinal cord as well as the spinal column, with no side effects to the patient.

He raised the money, negotiated with Hitachi and the Japanese government to deliver it at unprecedented speed, and meanwhile got the hospital to knock down walls and rebuild areas to make room for it.

His official title at Stoke Mandeville (and at Broadmoor, and at Leeds Infirmary, where he performs similar benefactions) is “voluntary helper” – but his help is quite breathtaking in its scope. In 1988, the Department of Health suspended the whole management board of Broadmoor and put Savile in charge of running the place, which he is still doing with every apparent success.

He raises money and also gives his own money, channelling nine-tenths of his income into two charitable trusts. He earns a BBC salary as presenter of Jim’ll Fix It, and the World Service radio programme Savile’s Travels, and is a paid consultant to Thomas Cook, the travel agents. But most of his income comes from personal appearances, for which he charges a minimum of five figures. “I don’t even get out of bed for less than £10,000,” he says, explaining that if he charges a lot, the event is well organised, whereas if he doesn’t, it isn’t.

“I went to a thing recently in a field with some lovely people, but when I got there, there was no raised platform and no microphone so how was the audience meant to see me? And they all go, ‘Oh yeah. We never thought of that.’ Now if they’d paid the ten grand, they’d have set to work with a great to-do, you see.” This makes sense, but sometimes comes as a shock to people who imagine that because Savile is charitable he is also unworldly. He isn’t.

Many businesses and organisations use him as a conduit to the Royal Family; he can pick up the telephone to most of them and has long worked with Prince Charles (“the most caring fellow I’ve ever met – oh, unbelievable”) on the problems of the disabled. He is an habitué of Highgrove and Buckingham Palace, of No 10 and Chequers, where he often spends Christmas or New Year – though he carefully points out that he has been friendly with all the past four Prime Ministers because Stoke Mandeville is Chequers’ local hospital.

Anyway, he is very, very well connected; many multinationals use him as a consultant and not just for PR purposes but for marketing advice. To the public, he remains the silver-haired, track-suited jester, but those who have worked with him take him very seriously indeed.

Still, his jester image may have made his knighthood slower than it would otherwise have been. “I would imagine that I unsettled the establishment,” he agrees, “because the establishment would say, ‘Yes, Jimmy’s a good chap but a bit strange... a bit strange.’ And I think maybe in the past I suffered from the vulgarity of success. Because if you’re successful in what you do, you can become a pain in the neck to a lot of people, especially if you’re doing it in a voluntary manner, right?”

Right. So being awarded a knighthood was a joy and an honour. More interestingly, he says it was also a relief. For the past several years, tabloid journalists have been saying that he must have a serious skeleton in his cupboard, otherwise he would have got a knighthood by now. “Ooh ay, I had a lively couple of years, with the tabloids sniffing about, asking round the corner shops – everything – thinking there must be something the authorities knew that they didn’t. Whereas in actual fact I’ve got to be the most boring geezer in the world because I ain’t got no past. And so, if nothing else, it was a gi-normous relief when I got the knighthood, because it got me off the hook.”

What he says about tabloid journalists is true. There has been a persistent rumour about him for years, and journalists have often told me as a fact: “Jimmy Savile? Of course, you know he’s into little girls.” But if they know it, why haven’t they published it? The Sun or the News of the World would hardly refuse the chance of featuring a Jimmy Savile sex scandal. It is very, very hard to prove a negative, but the fact that the tabloids have never come up with a scintilla of evidence against Jimmy Savile is as near proof as you can ever get.

I wasn’t sure whether Sir James actually knew what the particular skeleton in his closet was supposed to be, though I notice that he told The Sun five years ago that he never allowed children into his flat. “Never in a million years would I dream of letting a kid, or five kids, past my front door. Never, ever. I’d feel very uncomfortable.” Nor, he said, would he take children for a ride in his car unless they had their mum or dad with them: “You just can’t take the risk.”

Still, I was nervous when I told him: “What people say is that you like little girls.” He reacted with a flurry of funny-voice Jimmy Savile patter, which is what he does when he’s getting his bearings: “Ah now. Sure. Now then. Now then. First of all, I happen to be in the pop business, which is teenagers – that’s No 1. So when I go anywhere it’s the young ones that come round me.

“Now what the tabloids don’t realise is that the young girls in question don’t gather round me because of me – it’s because I know the people they love, the stars, because they know I saw Bros last week or Wet Wet Wet. Now you, watching from afar, might say ‘Look at those young girls throwing themselves at him’, whereas in actual fact it’s exactly the opposite. I am of no interest to them, except in a purely platonic way.

“A lot of disc jockeys make the mistake of thinking that they’re sex symbols and then they get a rude awakening. But I always realised that I was a service industry. Like, because I knew Cliff [Richard] before he’d even made a record, all the Cliff fans would bust a gut to meet me, so that I could tell them stories about their idol. But if I’d said, ‘Come round, so that I can tell you stories about me’ or ‘Come round, so that you can fall into my arms’ they’d have said: ‘What! On yer bike!’ But because reporters don’t understand the nuances of all that, they say, ‘A-ha.’”

This seems a perfectly credible explanation of why rumour links him to young girls. It still doesn’t explain the great mystery of his non-existent love life. His name has only ever been linked to one woman, his mother, whom he called the Duchess.

He was devoted to her – the more so, perhaps, because, as the youngest child of seven, he’d had a fairly scant share of her attention. “I wasn’t her favourite by any means; I was fourth or fifth in the pecking order.” But when he became famous, he laid his fame and money at her feet, and they had l6 years before she died in 1973 where she had “everything”. He once told Joan Bakewell: “We were together all her life and there was nothing we couldn’t do. I got an audience with the Pope. Everything. But then, I was sharing her. When she died she was all mine. The best five days of my life were spent with the Duchess when she was dead. She looked marvellous. She belonged to me. It’s wonderful, is death.”

(Incidentally, he has an enthusiasm for dead bodies in general, which can be quite unnerving. The first time I ever met him, eight years ago, he raved on about all the bodies that came his way in the mortuary at Leeds Infirmary and how he wished he could take the healthy eyes from one and the good bones from another to repair his living patients at Stoke Mandeville. He sounded like Dr Frankenstein.)

But back to his love life. “You must have had some sex at some time,” I tell him, and Sir James looks pained.

“Well. I would have thought so. But it’s rather like going to the bathroom. I’ve never been one to explain what I do when I go to the bathroom and I’m not a kiss-and-tell punter. All I can say is that I’ve never ever got anybody into trouble; I’ve never knowingly upset anybody; and I’ve always been aware that in my game there is a clear line between infatuation and actual, genuine liking. Other than that, you must draw your own conclusions.”

Well. One safe conclusion is that people who equate sex with going to the bathroom don’t like it very much. His views on sex and love are cynical; he said in passing that “sex was like what they say about policemen – never there when you want one” and that “it so happens that it is illegal to have sex on tap – unless you happen to be married, in which case you end up with a wife having a headache.”

He says that he has never been in love, never had a live-in girlfriend, never been even within shouting distance of getting married. He claims that he decided this as early as his twenties, soon after he was injured in a mining accident and became a disc jockey around the Mecca ballrooms of the North.

“I was too busy for that. The pop business was a tremendous, lively business and each day was a mushroom – there was only that day and there was only that night. It’s a very peculiar lifestyle but I realised that, in order to succeed, I would have to actually live the business. And I couldn’t do that and live a normal human-being life as well – it doesn’t work. Look in any of the papers – well-known people who try to lead normal lives, it invariably doesn’t work out.

“Now bearing in mind that I’m not particularly paternal, and that I wasn’t yer actual relationship-type person that must get married, must go through the normal thing, I thought: ‘Because I choose to be in this business and because the track record of the business is that marriage doesn’t work out, therefore I won’t even think along those lines.’

“Now that makes you different, it makes you strange, and people then try to stick their theories on you to account for the fact that you’re not married. But what they don’t take into consideration is the awesome logic of it all.” But surely this is the awesome logic of cutting off your nose to spite your face? It is logic carried to the point of insanity. Isn’t it better to have even an imperfect relationship than no relationship at all?

“No! I don’t agree. My life is the greatest life in the world. The greatest life in the world! You go to bed, you haven’t a care in the world; you get up, you haven’t a care in the world. It’s fun – do you understand? So why should I spoil a lot of fun?”

His six siblings are all married – “they’re all nice and normal” – and he has whole tribes of nieces and nephews, about 47 of them at the last count. When I ask if he is a good uncle, he immediately starts talking about money: while the Duchess was alive she was his sole beneficiary; when she died, he made his brothers and sisters his beneficiaries, and if any of them die he may, or may not, include their children in his will. He says he speaks to most of his siblings most weeks, but it’s physically impossible to keep up with all their children and grandchildren. “We’re a close family, but we’re a very common-sense family. Our common sense is not to everybody’s liking, but that’s all there is to it.

“I quite envy people who have been in love,” he admits, “and I would be perfectly happy to fall in love today. But how could I, with my lifestyle? I don’t have girlfriends because it’s not fair, the same as I don’t have plants because I’d never be back to water them, and I don’t have cats and dogs, and I don’t have kids because I’d never be there to see them.”

This is true. His lifestyle is unique and really unsharable with anyone else. In the week I met him, he’d been to Crewe to open a school for children with learning difficulties, to Liverpool to visit Broadmoor’s sister hospital, Ashworth, to Leeds Infirmary to attend their gala, to Newcastle to do some radio programmes, and on to Glasgow to run an exhibition race for charity.

He’d come back to London overnight on the sleeper in order to meet me in London at 9am, and was then going on to a business meeting and to Stoke Mandeville to “open” their new machine.

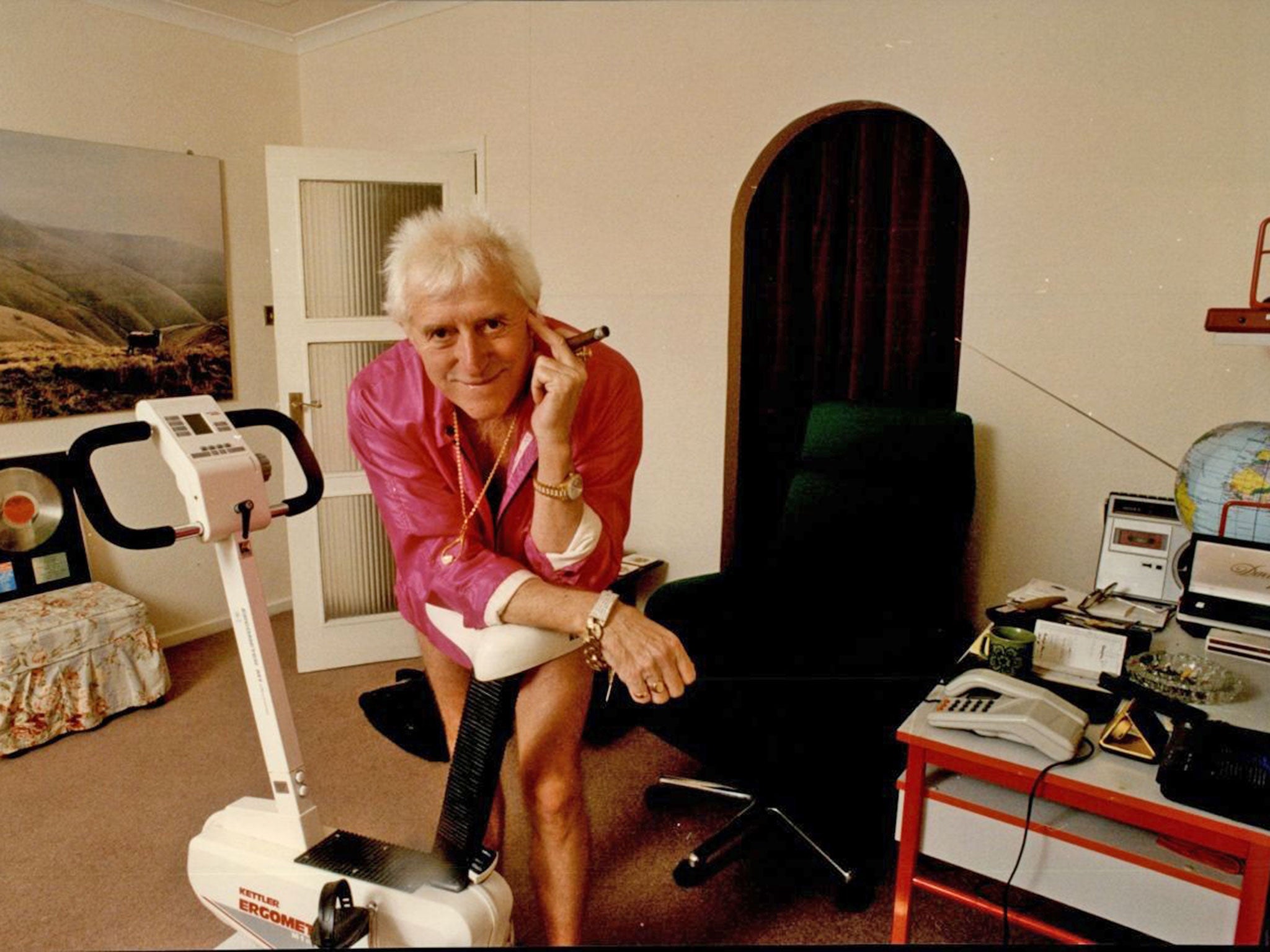

He rarely spends two consecutive nights in the same bed, and he has beds – you can hardly call them homes – two in Leeds (one at the Infirmary) and one each in London, Scarborough, Peterborough, Bournemouth, Stoke Mandeville, and Broadmoor. The London pad, a service flat near the BBC, is probably typical or slightly more luxurious than most: it is a one-room cell with a fold-down double bed, a large television tuned to Teletext, a closet full of tracksuits, a blown-up photograph of the Yorkshire Dales, and an empty kitchen.

“But where do you keep your things?” I ask him.

“What things? I have seven toothbrushes and seven telephones, one in each place.” “But you must have some things. Souvenirs, ornaments.” “Yeah, there’s one,” he says, pointing to a huge, staggeringly ugly silver-gilt trophy on top of the television. “That’s the Male Jewellery-Wearer of the Year Award from the British Jewellery Association. I have souvenirs in all my places.”

He seems genuinely delighted with the trophy, both as an objet and as an award. He enjoys a bit of a flash, like his Rolls-Royces (he is now on his 17th) and the gold and diamond Rolex watch on one wrist and diamond name-bracelet on the other. But all these he regards as tools of the trade – “I’m in a flash game. People like a bit of glamour, a bit of pizazz. They wouldn’t like me to come on the bus.”

He is not an aesthete, not a gourmet, not a sensualist. His idea of relaxation is running in marathons and half-marathons, usually for charity. He eats whatever horrible snack or sandwich is most quickly available; he never drinks alcohol; he never wears anything other than tracksuits.

The only glimmers of self-indulgence are the fat Havana cigars he smokes regularly and the annual cruise he takes by way of holiday.

But even on holiday, according to the Cunard PR Eric Flounders, who has often travelled with him, “he gives all his time to other people. He is quite wonderful, actually. He never tells anyone not to bother him, and if he sees someone he thinks needs some particular attention, he goes out of his way to do it.” Like his hero, the Prince of Wales, he tends to make a beeline for people in wheelchairs, though he himself insists he doesn’t: “I talk to everybody because I’m gregarious.”

He works incredibly hard but he says this is only because people ask him to: “Left to meself, I would never move out of the chair. I’d smoke cigars, look out of the window, watch the Teletext, see if I can make a few quid, listen to some jazz on the radio. But the phone rings, and somebody says ‘Can you? Will you?’ and the mail comes – I get 500 letters a week – and being an obliging type of punter, I say ‘Yes’, if I can. So I finish up having a very hectic life, but that’s at the diktat of other people – I don’t look for it. Left to meself, I’d just be wandering about.”

Incidentally, his business organisation consists of himself, his diary and the telephone. He has no agent, no manager, and never writes letters. Yet if he says he will open your fete on 14 July 1992, you can forget about it for two years and know that he’ll be there on the day.

It is a life of self-punishing austerity that seems like a long expiation for some lasting sense of guilt. His accountant, Harold Grumber, who has known him for 30 years, once said: “The most important thing for Jimmy is peace of mind.”

It is a constant theme of his conversation – his need to go to bed with a clean conscience, to feel that he has done his best. He says he is like a surgeon who can do five operations in a day and eight patients turn up: the trick is to do the five he can, and not allow himself to worry about the three that he can’t. But he obviously does worry about them, hence his inability ever to refuse a request if he can possibly fit it in.

He is a prickly man, a self-righteous man who cares for humanity, but not much for individuals. He has “thousands” of acquaintances but no confidants. He is very keen on reason, very distrustful of emotion: he boasts often of his “logic” and his membership of Mensa. He has total recall – “I can remember everything”. His image – the dyed hair, the tracksuits, the flash jewellery and above all the patter, which I would say is the most irritating thing about him – is a deliberate smokescreen designed to make stupid people think he is stupid. Once he knows you well enough to drop the patter, he talks like the exceptionally hard-headed Yorkshire businessman he is – albeit a businessman with a social conscience.

But his conversation is all facts, all specifics. He has no time for speculation, for introspection, and especially not for self-analysis, which he regards as “soft”.

He became seriously annoyed when I kept asking about his childhood, and snapped: “We had no time for psychological hang-ups. We were just survivors, all of us. None of that ‘Oh, I was ignored as a child’ – what a load of cobblers! I don’t know whether I was or I wasn’t. All I know is that nothing particular wrong happened, and I had a good time.”

I ask whether he ever suffered from Bob Geldof’s “compassion fatigue” and he says no, he wouldn’t let himself, because that would be illogical.

But he admits that “I’m constantly taking stock of what I’m doing so that I do it – hopefully – for the right reasons. I can’t guarantee I’m doing it for the right reasons because nobody can guarantee that. But I do it by instinct and instinct tells me I’ve no reason to believe I’m doing it for the wrong reasons, therefore I just carry on and do it.

“And thank goodness, having no wives, no homes, no kids, no dogs, no plants to water, at least you’ve got blinkers on and you can attend to what comes in on the rag and bone [phone].”

Why do so many people find him so insufferable? Partly, it is a class thing: he operates at a folksy level designed to please little old grannies in Scunthorpe, which goes down badly with the middle classes. Many showbiz stars can turn on the man-of-the-people stuff and then turn it off again when talking to journalists, but Savile never turns it off because it is entirely genuine.

It means, though, that he rarely talks to people as equals; he is either the licensed jester, as at Chequers or Buckingham Palace, or the patron, the glittering bestower of gifts. He spends a lot of time with people in extremis – the recently bereaved at Leeds Infirmary, or more harrowing still, the patients and their families at Stoke Mandeville. (An awful lot of the patients at Stoke Mandeville are young people who have been disastrously injured in riding or sports accidents and now face the rest of their lives as paraplegics.)

Touring the Stoke Mandeville wards with him is a disconcerting experience: when he coos over a young woman paraplegic “A-ha, now I can have my way with you, my dear!” one can only pray that she appreciates the joke. I remember the most frightening thing anyone ever said to me was when I was being wheeled in for a back operation and the junior doctor remarked cheerily, “We’ll have you walking again in two weeks – and if we don’t we’ll send Jimmy Savile to visit you.” Much as I admire Sir James Savile, he is someone I never ever want to be visited by.

“You do seem to be almost saintly...” I tell him. “No, no, no, no, no,” he exclaims, horrified. “Why don’t you, instead of saying ‘saintly’, say ‘You do seem to be totally practical?” But perhaps that is true of saints, too.

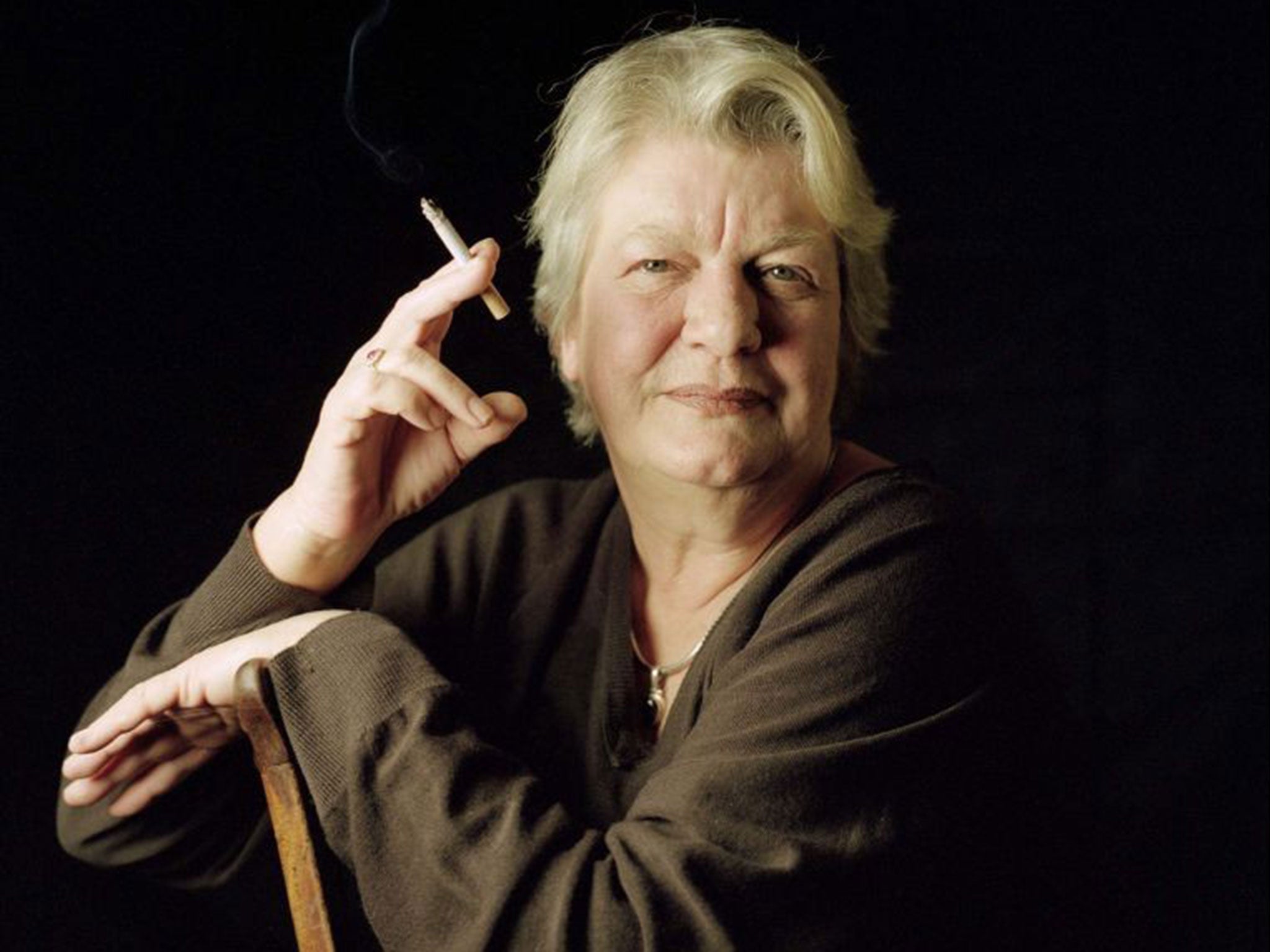

'It had to be tackled'

When this article was first published in The Independent on Sunday in 1990, many readers complained. How dared I ask Sir Jimmy Savile if he liked little girls? He was newly knighted. He was a friend of the Royal Family. He had raised millions for charity.

But when I was preparing for the interview, I was struck by how many people – mainly journalists, but also friends, taxi drivers, ordinary members of the public – said in almost identical words: “You know he likes little girls?” None of them could ever produce any evidence, or the names of girls he might have abused, but I felt the rumour was so widespread that it had to be tackled.

My first Fleet Street editor, Sir John Junor at the Sunday Express, had taught me that you could not be sued for libel if you framed something as a question and then made sure to print the interviewee’s answer in full – which is what I did with Jimmy Savile. Of course, I didn’t know that he liked little girls – all I knew was that it was a very widespread rumour that had not yet appeared in print. I thought perhaps it would stir up some responses from his victims, but it didn’t as far as I know, nor any response from Savile himself. But I was quite proud of at least floating the idea.

When a short extract of the article was reprinted after Savile’s death, I then got another wave of flak from readers, but this time saying that if I knew Savile was a paedophile, why hadn’t I exposed him? Why was I so pusillanimous? But, of course, I didn’t “know” that he was a paedophile, I only knew the rumours. And the laws of libel – then as now – would not allow me to say any more than that.

Lynn Barber’s latest book of memoirs ‘A Curious Career’ (Bloomsbury, £16.99) is available now