Fidel Castro obituary: The Cuban revolutionary who defied 10 US presidents

Few people on his island, not even its dissidents, ever lost the habit of referring to him simply as ‘Fidel’. He billed himself as David to the Goliath across the Florida Straits, and became a giant on the world geopolitical stage

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.During half a century in power, Fidel Castro faced down no fewer than 10 US presidents, despite the fact that his Caribbean island is only around 90 miles from Florida. He died just two months before the fascinating prospect of a new relationship, for better or worse, between communist Cuba and US President-elect Donald Trump. Whether you loved him or hated him – and there were few in-betweens – Castro was the world’s longest-serving political leader before he stood down and handed over de facto power to his brother Raul in 2008. Even thereafter, there was never any doubt as to who was calling the shots.

Best remembered by his olive fatigues, trademark military cap and (until forced to give them up for health reasons in 1985) his giant Cohiba cigars, he liked to be addressed as Comandante (Commander) but was officially known as el Jefe Máximo (the Maximum Leader).

Few people on his island, not even its dissidents, ever lost the habit of referring to him simply as “Fidel”. Ruling initially over only six million people (rising to 11 million), he billed himself as David to the Goliath across the Florida Straits, and became a giant on the world geopolitical stage.

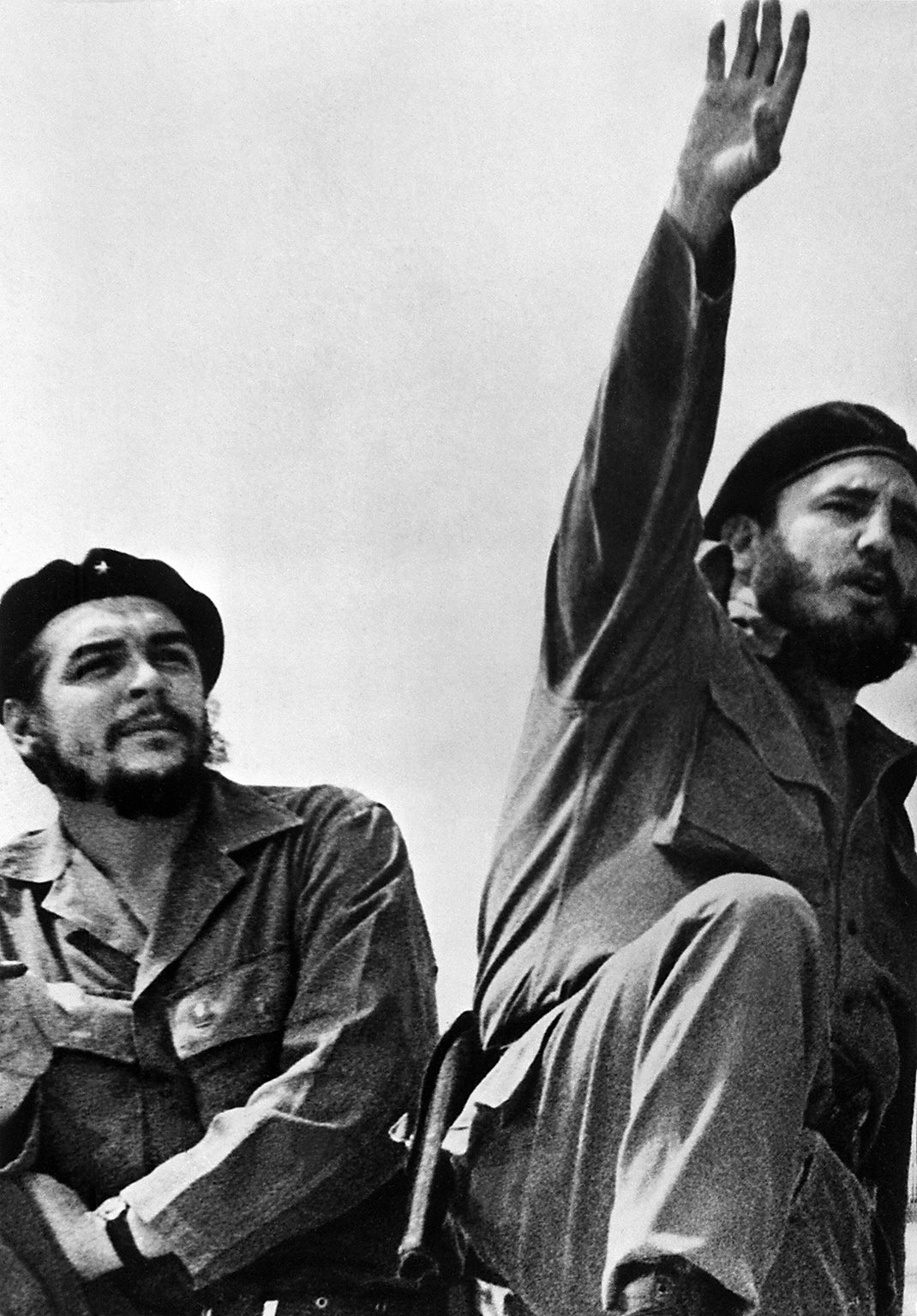

He and his Argentinian comrade Ernesto Ché Guevara, both bearded and handsome, became heroes to a generation or more, their revolution setting the tone for the 1960s as posters of the two sprouted on student bedroom walls around the world. They became spearheads of change, particularly throughout a Latin America dotted with dictatorships.

Ironically, Castro might have gone on to fulfil his promise of democracy for Cuba had it not been for American paranoia and an over-reaction to his success, initially from President Dwight Eisenhower, who pledged to bring the young upstart down.

At the time of the revolution, Castro was not, at least openly, a communist and had never preached Marxist-Leninism, or even socialism. It was a further two years before, prodded by US antagonism, he declared himself a communist and began turning his island into a one-party state modelled on the Soviet Union.

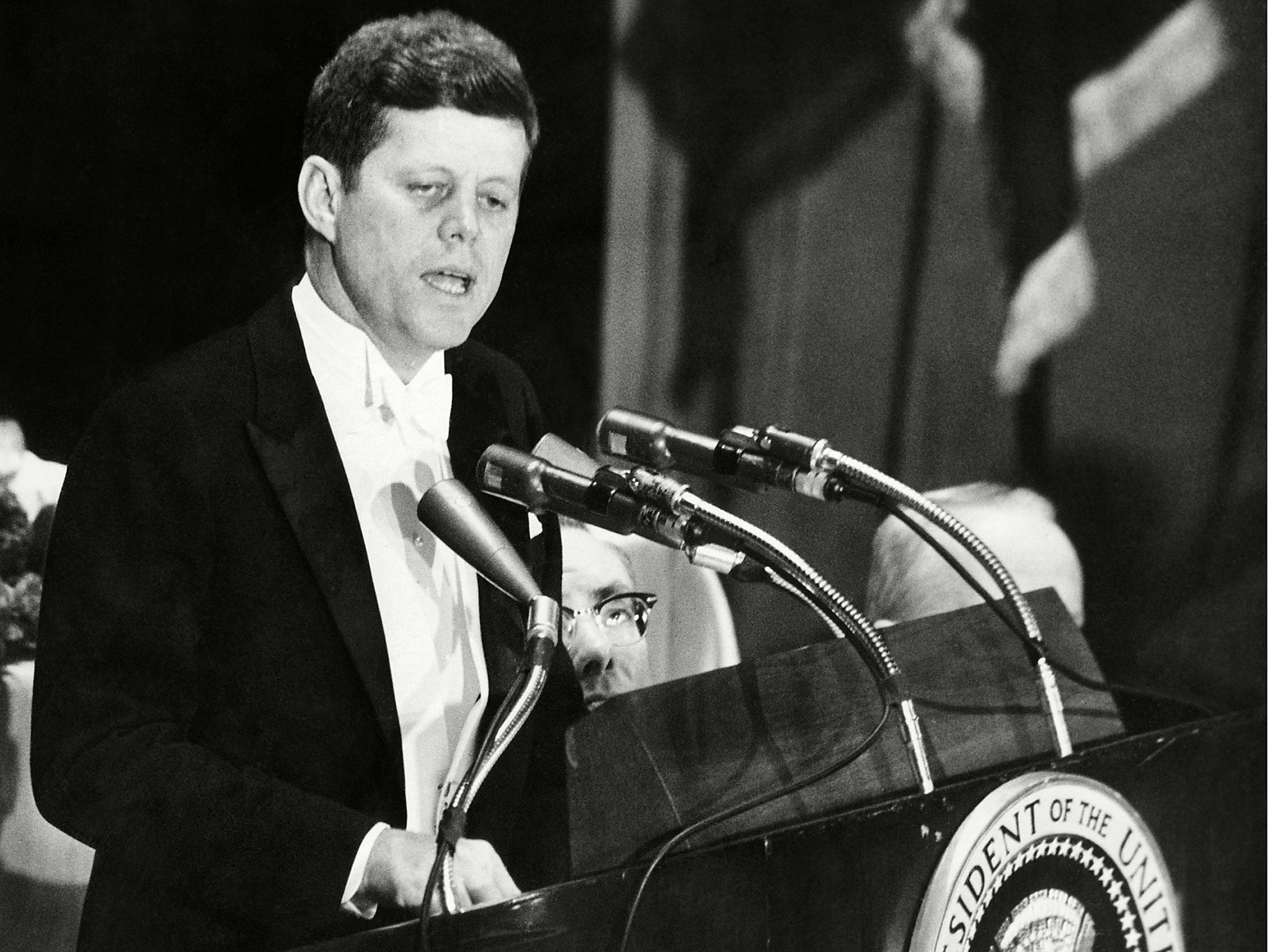

A rift with Eisenhower’s successor, John F Kennedy, over the disastrous 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion attempt by US-based Cuban exiles pushed Castro into the arms of the other superpower, the Soviet Union, which had been angling for a base in the Caribbean.

Castro will always be the man who, backed by Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, brought the world to the brink of a Third World War, a potentially cataclysmic nuclear one. Soviet nuclear missile-launching pads had been spotted on Cuba by an American U-2 spy plane, the missiles pointed towards the US. For most of those 13 days in October 1962, the three players – Castro, Khrushchev and Kennedy – held world peace in their hands.

Castro and Khrushchev, his new “sugar daddy”, engaged in a dramatic face-off with Kennedy, a political poker game with the highest of stakes. The spy plane had captured photographs showing that the Soviets were assembling 39 nuclear missiles in five Cuban bases, all apparently pointed at US cities. JFK waited a week before he went on television to tell the nation sombrely that the United States was on the brink of war if the Soviets did not remove the missiles.

The confrontation gripped the world for two weeks. Castro had reportedly asked Khrushchev to launch a nuclear first strike against the US if Cuba were invaded. The Soviet leader rejected a first strike, but his field commanders in Cuba were said to have been cleared to use tactical nuclear weapons if they themselves were attacked.

Then, after much bluster, Khrushchev backed down and ordered the missiles dismantled. But Castro effectively scooped the poker game pot when Kennedy, in a quid pro quo to the Soviet leader, pledged not to invade the island. That promise has been kept by US presidents ever since and hopefully President-elect Trump, when in office, will see no reason to break that promise.

Castro made various attempts at rapprochement with the US over the years, notably during the era of President Jimmy Carter and the early years of President Bill Clinton. But the congressional clout of the US Republicans, constantly lobbied by the relatively wealthy and vote-controlling Cuban exile population in Florida, coupled with Castro’s perception that having the US as an enemy might be his own saving grace in terms of domestic control, kept them apart.

“A revolution not faced with an enemy runs the risk of falling asleep,” the Maximum Leader once told his people.

Castro’s friends ranged from Colombian writer Gabriel García Márquez and Argentinian footballer Diego Maradona to UK politician George Galloway, who once hinted he had had a midnight “skinny-dip” with the Cuban leader on the island.

But most Cuban exiles despised the Cuban leader; most democratic governments opposed and isolated him; and each of that 10-man line of US presidents sought to undermine him to varying degrees, at least until President Barack Obama sought some kind of détente two years ago.

The CIA, at the height of its Cold War paranoia, is known to have organized most of the 30 confirmed attempts to assassinate him, while he himself claimed there had been at least 300 plots to end his life.

The most famous attempts involved an “exploding” Havana cigar which failed to go off, a strawberry milk shake spiked with an overdose of LSD and a doctored bottle of shampoo designed to burn off the famous beard crucial to his image. Castro’s response for many years was to live as something of an Arafat-esque nomad, flitting among secret residences. He insisted his security men first taste food from his plate. On his trips abroad, two identical Soviet-built airliners flew together and he chose which one to board at the last minute, halving his chances of dying if anyone tried to shoot him down.

One security guard who fled Cuba said el Jefe Maximo wore only brand-new underwear every day, burning used pairs, because he feared the CIA might chemically “doctor” his underpants in the wash.

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz was born in Birán, a sugar plantation village near Mayarí in Oriente (now Holguín) province, on 13 August 1926. Some versions put the year of his birth as 1927, saying his parents registered him as a year older when they were trying to get him into a nearby Jesuit school. The mystery remained for half a century, until 13 August 1976, when Castro acknowledged a 50th birthday greeting from Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev.

Castro’s father, Angel Castro Argiz, was an immigrant from the rugged north-western Spanish region of Galicia who became a wealthy cattle rancher in Cuba. He had first gone to Cuba to fight for Spain in the Spanish-American war in 1898, returned home, but went back to Cuba in 1905 because he had spotted a land of opportunity. It was from his father that Castro developed a love for Galician gaita, or bagpipes.

In 1992, at the age of 66, Fidel Castro went to Spain to visit his father’s birthplace, little more than a barn, for the first time. As a correspondent for The Independent, I was there in that tiny barn, while a friendly Castro security man pressed a pistol through his guayabera shirt against my ribs in case I misbehaved. The security man and I then saw distinctly what few must ever have seen before, a tear running down Castro’s cheek and into the world’s most famous beard.

Most historians believe that Castro and his brother Raúl, five years his junior, were born illegitimate to their father and the family’s maid, Lina Ruz, while their father’s first wife, María Argota, was still alive. After the latter died, Angel Castro married Lina. Fidel never denied this version and took Lina’s surname as his maternal name. In the Caribbean and Latin America of the time, such a soap opera story was far from rare and little frowned upon.

According to relatives, Fidel showed his first sign of rebellion at the age of six when he demanded to go to school “or else I’ll burn the house down”.

He was described as a good but not brilliant student, noted more for his towering physique and his gift for sports – climbing, swimming, football, volleyball, basketball and baseball. “He had a good arm,” recalled one schoolmate, referring to his baseball pitching. When he left school, his yearbook entry read: “The book of his life will undoubtedly be filled with brilliant pages.”

It was after entering the University of Havana as a law student in 1945 that Castro found his calling. During a time of turmoil both in Cuba and Latin America, he established himself as a radical left-wing student leader, though avoiding the Young Communists and joining the Orthodox Party, more like social democrats and the only party he ever belonged to before the 1959 revolution.

Struck by the parallel with downtrodden sugar-cane workers, he later admitted being strongly influenced by an English political economy textbook in which he said he never forgot the phrase “jobless workers froze despite abundance of coal”. Although Castro did not declare himself a communist until well into his revolutionary leadership, the American biographer Lionel Martin quoted him as saying he read The Communist Manifesto while a student. “For me, it was a revelation. I was converted to those ideas,” Castro said, according to Martin, a long-time resident of Cuba.

Yet he remained, at least on the surface, a democrat and was preparing to run for parliament for the Orthodox Party in 1952 when Batista seized power in a coup d’état. Castro, already known as a fiery campus orator, went underground but, travelling the country in a beaten-up Chevrolet and calling himself Alejandro, regularly surfaced to give anti-Batista speeches.

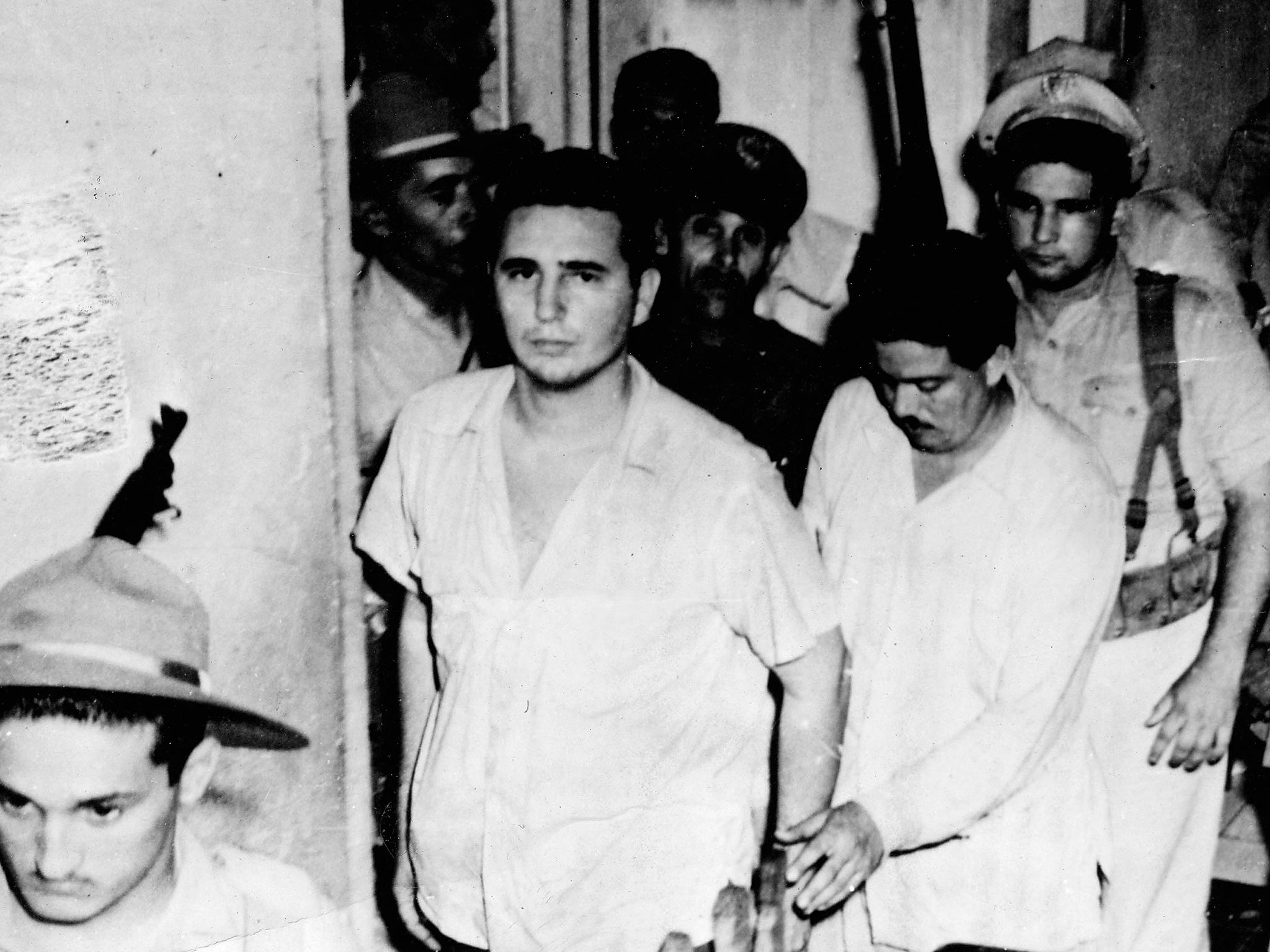

On 26 July 1953, he and a motley band of more than 100 men and women launched an ill-fated assault on Batista’s Moncada barracks in the eastern city of Santiago de Cuba. Of the assault force, who drove into Santiago in a fleet of old American saloon cars, only three were communists, including Castro’s brother Raúl. They included a butcher, a taxi driver, a dentist and a librarian. By the end of the day, 10 assailants were dead and 30 captured. Castro was detained a week later and sentenced to 15 years in prison after a trial in which he uttered the famous words: “Condemn me. It does not matter. History will absolve me.”

Freed after two years, including six months in solitary confinement, he moved to Mexico, where, by chance, he met a young Argentinian doctor bent on making the world a better place. It was over endless coffee cortado and big cigars in Mexico City’s La Habana café, on a corner of the famous zocalo central square, that Castro and his new compadre Ernesto Ché Guevara plotted to oust Batista. Amid thick cigar smoke and coffee steam, two pairs of idealistic eyes met and smiled. Castro wanted to free his island from dictatorship. Guevara wanted to help people but also yearned for adventure. History was about to be made.

With funds he collected from sympathisers, Castro bought a rickety 38ft motor boat previously owned by an American who had named it in honour of his grandmother. Castro didn’t have time to rename her and the Granma was later to become a symbol of the revolution, as well as the name of a province and of the Communist Party newspaper on the island.

Castro, Guevara and 80 other men set sail from Tuxpán on 25 November 1956. But the boat was built to sleep only eight and Ché Guevara slept mainly on the bow. After a rough week at sea, the 82 hungry, thirsty, sick and exhausted revolutionaries landed at Los Cayuelos, Cuba, before dawn on 2 December to be met by a startled woodcutter called Angel Perez. “Don’t be afraid. I am Fidel Castro and we’ve come to liberate the Cuban people,” the bearded group leader reportedly told him.

Only 12 of the original 82, including Castro’s brother Raul, survived but that 12 had grown to more than 1,000 by the time the revolutionaries finally triumphed when Batista panicked and fled the country on New Year’s Day 1959. Mobbed by delirious villagers all the way surrounding his Jeep, Castro took a full week to reach the capital to a hero’s welcome on 8 January. When he made his first speech a white dove landed on his shoulder, seen by superstitious Cubans as a sign that he was their true liberator.

Many in the world agreed. Eisenhower quickly recognised the new regime. So did the Vatican. Batista’s Cuba had become legendary for its widespread corruption, gambling and prostitution – “the United States’ brothel”, some had called it – much of it controlled by the American mafia boss Lucky Luciano. Castro was invited to the White House and met the Vice President, Richard Nixon.

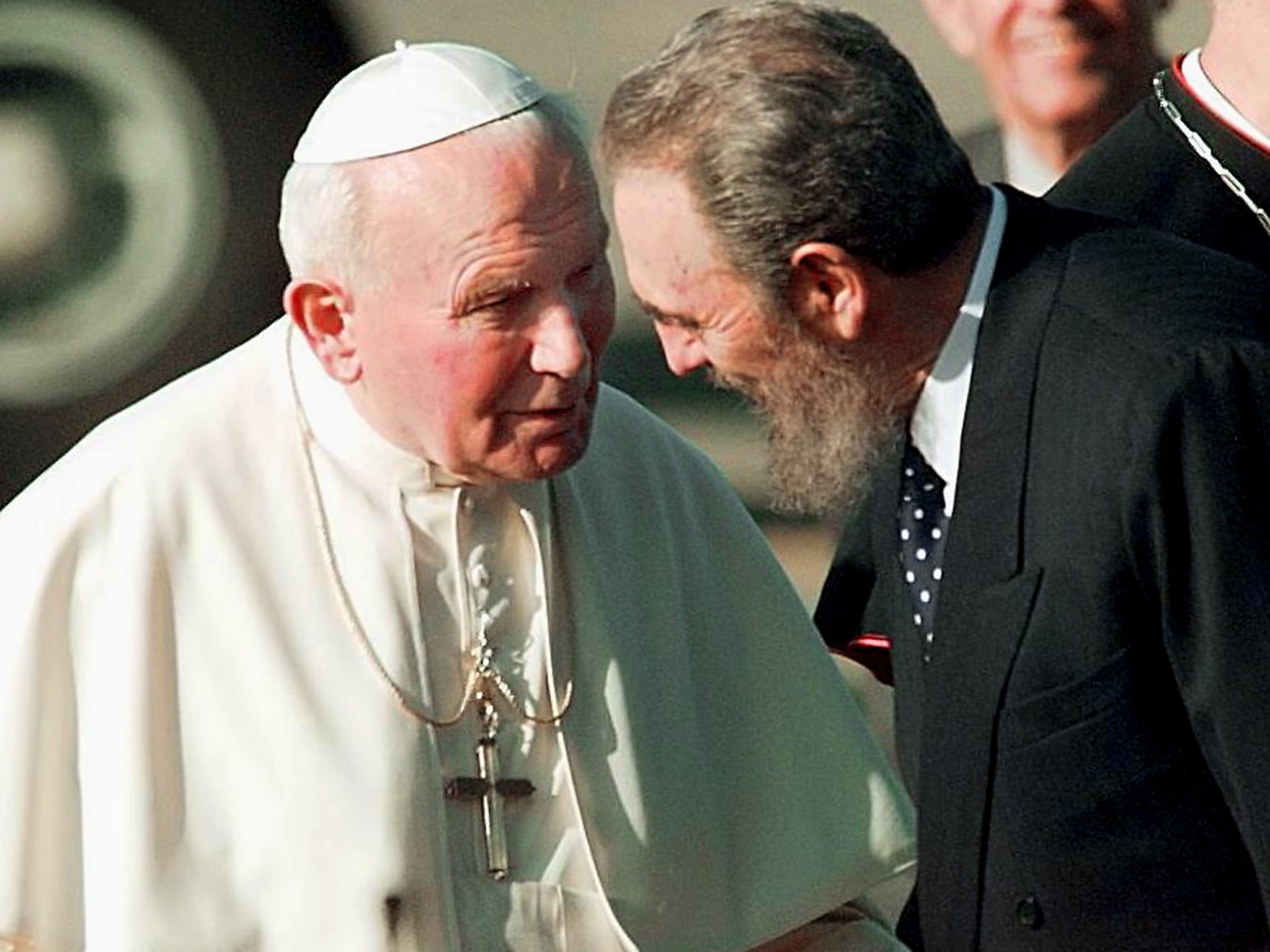

But reports emerged of summary trials and executions of Batista soldiers, sympathisers and even some of Castro’s own men who criticised his personality cult. One of his top commanders, Eloy Gutiérrez Menoyo, spent 22 years in jail for criticising Castro. Castro modified the constitution to include the death penalty. One Batista army captain, tried in a sports stadium, compared it with being thrown to the lions in ancient Rome. Reports also began of the expulsion or jailing of priests, causing a rift between Castro and the Church, a rift he eventually tried to bridge nearly 40 years later by inviting Pope John Paul II to the island in 1998.

Castro began nationalising properties and businesses, many of them belonging to US citizens, including the famous Bacardi rum distillery. He publicly received Soviet bloc weapons and spoke of revolution spreading throughout Latin America.

And so began an exodus of those Cubans who could afford to leave. Most settled in Miami, transforming it from a sleepy, English-speaking town with a large, elderly Jewish community to the throbbing bilingual, bicultural city it is today. The Cuban exiles became the focus of attempts to “free Cuba” and restore democracy and they became a powerful lobby influencing successive US presidents. Their pressure pushed Washington into imposing a trade embargo on the island, which continued throughout Castro’s rule. Needless to say, the Cuban exiles – los gusanos (the worms), Castro famously called them – celebrated his death, notably on their home turf of Miami’s Calle Ocho (8th Street but never referred to in English).

In early April 1961, with JFK having taken over from Eisenhower, rapprochement still seemed possible. But all that ended on 17 April of that year with the attempted invasion of Cuba by a band of 1,400 exiled Cubans trained and armed by the CIA. The so-called Bay of Pigs invasion, named after the beach where the exiles landed, quickly turned into a fiasco. The plan had initially been agreed by Eisenhower and his successor Kennedy had gone along with it without great enthusiasm. As it turned out, it ended any hope of a US-Cuban rapprochement, provided Castro with a useful distraction from domestic discontent and pushed him all the way into the arms of the Soviets.

The exiles, known as Brigade 2506, landed in Cuba around Playa Girón, at the Bahía de Cocinos (Bay of Pigs). They had been trained and armed in Florida by the CIA and were commanded by two CIA operatives. But they were engaged by a pre-warned Castro force of 20,000 men, including the Comandante himself, cigar in teeth and rifle in hand. What’s more, Kennedy got cold feet at the last minute and withdrew promised US air support. The invaders were sitting ducks.

They were routed, losing more than 100 men. At least nine were executed, but most were jailed for 30 years, though eventually amnestied. The hundreds of thousands of Cubans who fled to Florida after the revolution were never to forgive Kennedy or the Democrats for failing to provide the air support they had expected. As for Castro, the accounts of his personal actions in the battlefield added greatly to his popularity at home.

It had been on the eve of the Bay of Pigs that Castro, whose spies in Miami had no doubt tipped him off about a planned invasion, first spoke of a socialist Cuba. “They [the Americans] cannot forgive us for making a socialist revolution beneath their noses,” he said. It was only then, too, more than two years into the revolution, that red flags and bandanas began appearing in Havana, the clenched-fist salute emerged and a popular song swept the streets: “Somos socialistas, p’alante, p’alante, al que no le guste, que tome purgante” (“We are socialists, forward, forward, whoever doesn’t like it can go and take a laxative”).

By the end of 1961, almost three years after Batista was ousted, Castro announced for the first time that Cuba was a Marxist-Leninist state.

From the moment he made his first trip abroad, when he was welcomed like a god in Venezuela, Castro clearly saw himself as a modern-day Simón Bolívar, liberator of Latin America from the Spanish conquistadores. Pro-Castro guerrilla groups sprang up in Venezuela, Bolivia, Peru, Argentina, Colombia, Brazil and Central America, where Nicaragua’s Sandinistas, with Cuban arms and advisers, won their own revolution in 1979.

Thanks to his Soviet friends, Castro built up one of the Americas’ best-equipped armies. With no one to fight at home – successive American presidents stuck to JFK’s “gentleman’s agreement” with Khrushchev not to invade the island – the Maximum Leader took his revolution to Africa. By the end of the Seventies, thousands of Cuban troops had fought for Marxist causes in Angola, Ethiopia, Somalia and the Congo. (Ché Guevara was among those who fought in the Congo and was later killed in Bolivia, in 1967, while trying to export Castro’s revolution there.) Although Castro continued to speak highly of Ché throughout their lives, there was little doubt that the former became resentful of the latter after Ché became a greater cult hero than Fidel to millions around the world.

The return of the Cuban veterans from Africa, many of whom complained of lack of pay or pensions, added to Castro’s domestic problems, and dissidence spiralled. In 1980, after thousands of people invaded the Peruvian embassy in Havana in the hope of getting off the island, the Cuban leader was forced to open the floodgates. Thus began the six-month Mariel boatlift, when 120,000 disillusioned Cubans were shipped from the port of Mariel to Florida on boats sent by exiles and allowed by Castro to come ashore. At the same time, he took the opportunity to get rid of thousands of common criminals, rapists and psychiatric patients.

Even decades after the revolution, with hundreds of political prisoners in jail and much of the country undernourished, Castro could reasonably claim to have strong support among his islanders. He boasted to the end, with much justification, of Cuba’s advanced health service, of one of the highest literacy rates in the western hemisphere, of its low infant mortality rate, its state support for sports and the success of its sportsmen and women, and the fact that there was no outright poverty on the island in contrast to neighbouring Haiti and much of Latin America.

But the end of the revolutionary dream may have come first with the perestroika and glasnost of the Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev. Struggling to keep his own nation together, Gorbachev chopped away at the subsidies that had kept Cuba alive. Moscow began providing less oil to the island, and charging a higher rate for oil against Cuba’s sugar. By 1990, Moscow wanted hard currency, not sugar, for its oil, forcing Castro to initiate what he euphemistically called the “Special Period” – effectively a wartime economy. Rationing was stepped up, fuel became scarce, Havana’s old American sedans were seen abandoned by roadsides, bicycles and horses and carts returned to the street and graffiti saying “Abajo Fidel” (“Down with Fidel”) began appearing on walls. Afraid of reprisals, Cubans would simply point to their chin when referring to Castro in public, a reference to his beard.

Desperate for foreign currency, Castro launched his own version of perestroika and glasnost in the 1990s, allowing Cubans to have dollars openly for the first time, allowing joint business ventures with foreigners and eventually majority foreign ownership in some cases. In the last few years, tourism overtook sugar as the number one earner, but that brought its problems, notably blossoming prostitution and widespread resentment among hungry Cubans banned from the foreign hotels, pools, clubs and restaurants, unless they worked there. By the mid-1990s, foreigners could procure beautiful young Cuban girls for the price of a drink and a ham-and-cheese sandwich. The girls were not prostitutes; they were just happy to be allowed into the plush hotels.

As the economy collapsed, tens of thousands of Cubans tried to flee. Behind high walls around the country, they clandestinely built makeshift rafts from anything they could find, including old car bodies, and set sail, usually rowing, across the treacherous Florida Straits towards Key West. In 1994, Castro decided he was better off without the “ingrates”. He ordered his police to ignore the balseros (rafters) and they began leaving openly, even from the rocks below Havana’s famous Malecón seafront promenade.

In February 1996, just as Castro and President Clinton appeared headed for a rapprochement, Cuban Mig fighter planes shot down two light aircraft belonging to anti-Castro Cuban-American civilians from Miami, in international airspace over the Straits of Florida, killing two pilots and two co-pilots. The victims were from the respected Brothers to the Rescue group who were overflying the Straits in the search of rafters in difficulties.

As a result of the incident, Clinton did an about-turn on Cuba policy and backed the tough Helms-Burton Bill which tightened the screws on Castro’s regime. As more and more Cubans returned to their Catholic faith in the 1990s, the Pope visited the island in 1998, only to criticise Castro’s human rights record and call for greater freedom for Cubans. The Cuban leader did open up in certain areas, including permitting a certain degree of small private business. Cubans were allowed, for example, to open private restaurants in their homes, known as paladares.

In the US, meanwhile, it was becoming increasingly clear that the younger generations of Cuban-Americans, mostly in Florida, did not harbour the same hatred of Castro as their parents, many of whom had lost property or businesses after the revolution. Yet relations with Washington remained frigid, and Castro turned increasingly towards Europe. Spanish companies were at the forefront of Cuba’s tourism boom in the 1990s and into this century.

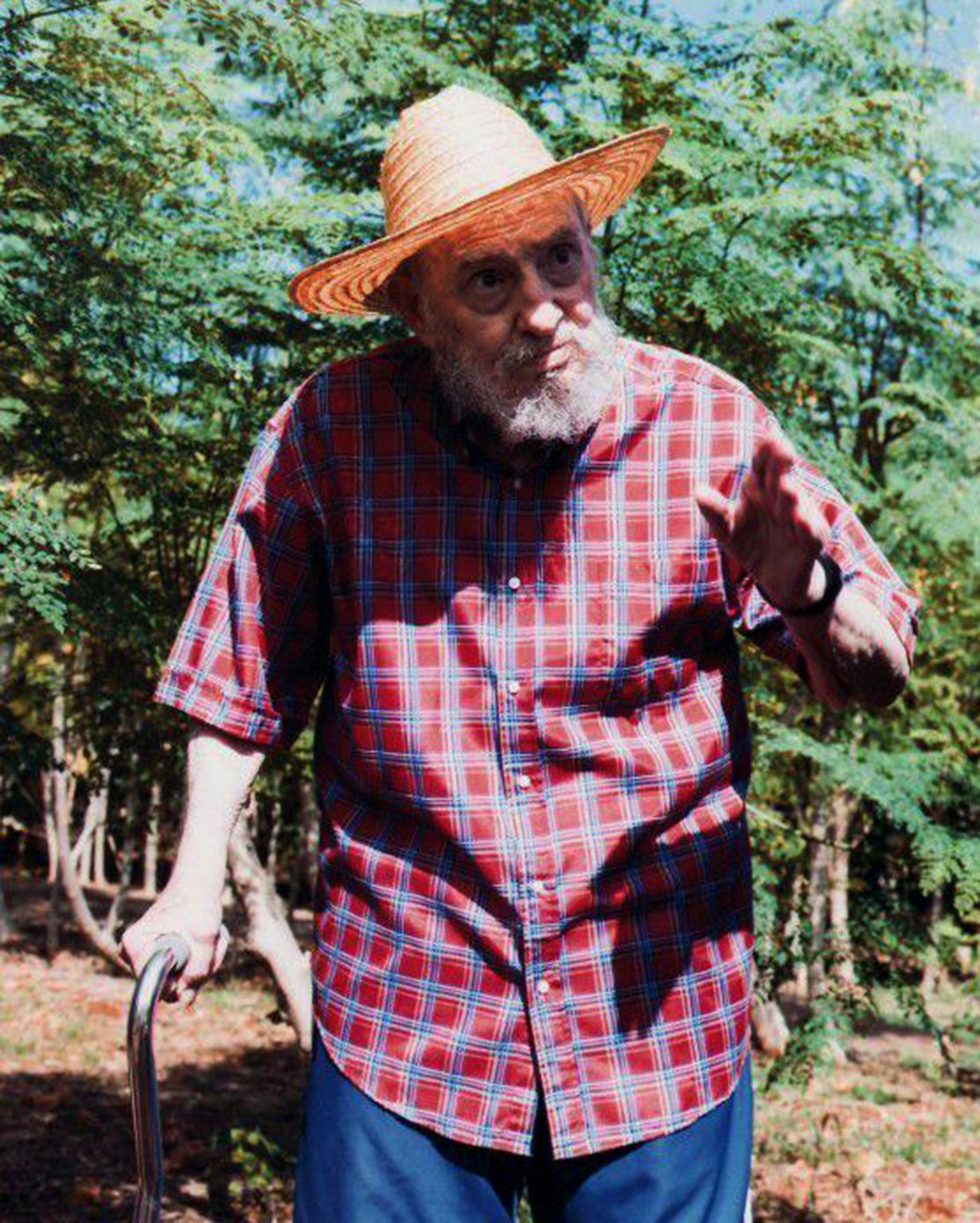

Castro appeared increasingly frail, though he still towered over most when he appeared in public. His famous bladder – he used to give speeches of six hours or more without a break – apparently weakened and he once interrupted a TV speech by walking out and telling the director to put on some music till he got back. Then, in July 2006, in a written statement read out by the President’s secretary, it was announced that he had undergone intestinal surgery and would hand over power temporarily to his brother Raúl. He disappeared from view, missing his 80th birthday celebrations.

Then, out of the blue, in the early hours of 19 February 2008, with most of his countrymen asleep, the Cuban state media quoted Castro as saying he was stepping down as president and commander-in-chief of the armed forces because of his health. He thus gave up the chance of scoring a half-century in power, and of seeing yet another hostile US president vacating the White House

Castro always tried to keep his private life a secret, but his basic home was a Havana villa known to his security entourage as Punto Cero (Point Zero).

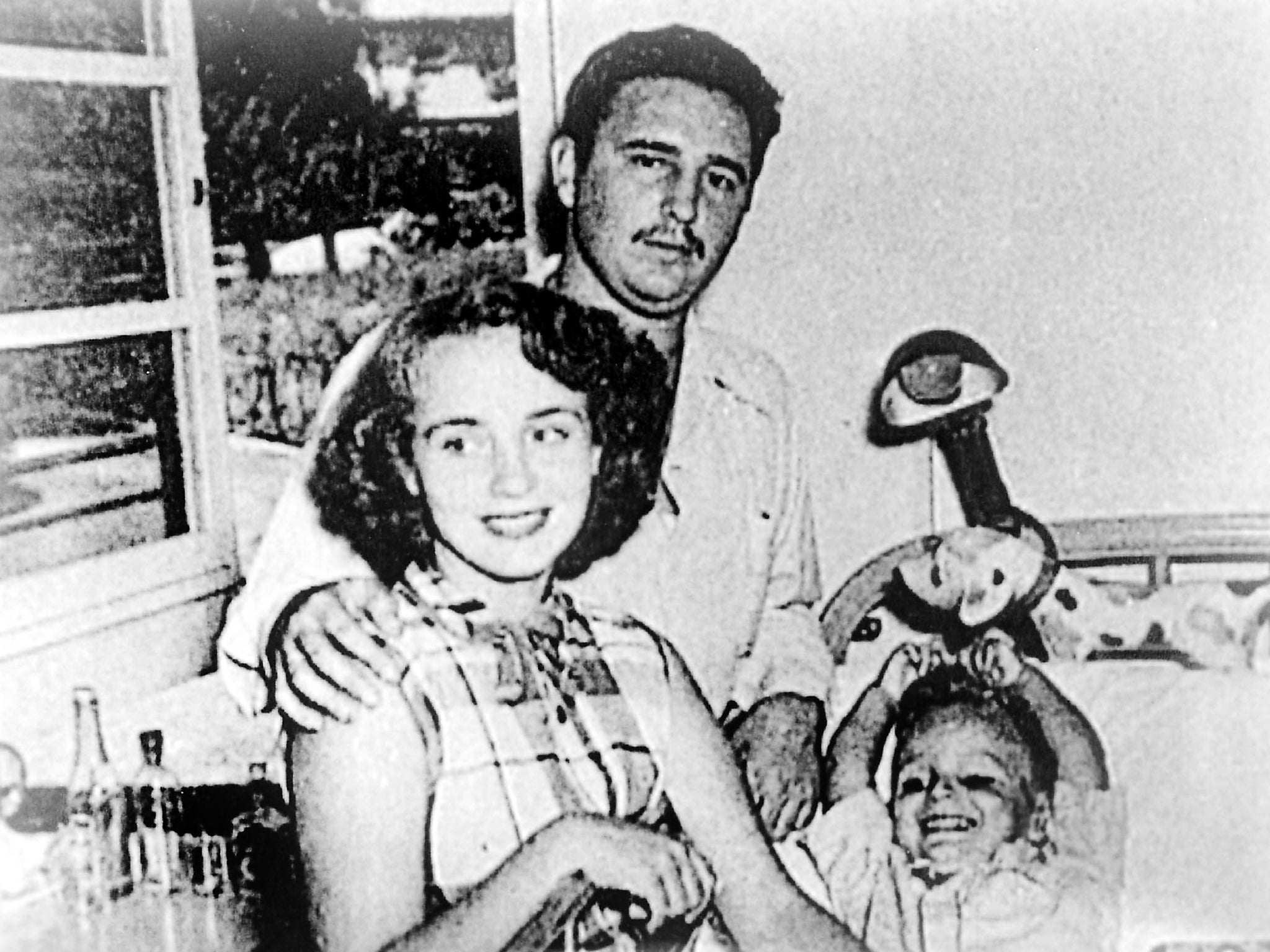

It was known that Castro married Mirta Diaz-Balart as a student in 1948 and that their son, Fidel Castro Diaz-Balart, widely known in Cuba as Fidelito (Little Fidel), was born the following year. The couple were divorced in 1955. (Mirta was last said to be living in Spain.) In the 1970s, Castro met Dalia Soto del Valle and they eventually married. They had five sons – Angel, Antonio, Alejandro, Alexis and Alex. Castro also never denied that Alina Castro, who fled the island in 1993, was his daughter by a former compañera in battle, Naty Revuelta.

In total, Fidel Castro was believed to have fathered nine children, but little is known about most of them. Alina was last known to be still in Florida, where she was a bitter critic of his regime. Fidelito, now in his sixties, formerly the head of Cuba’s Nuclear Power Agency, was last known to be a businessman in Havana.

After suffering ill health in 2006, Castro began transferring power to his younger brother Raúl and in 2011 officially stepped down to leave Raúl in charge. Raúl went on, mutually with President Obama, to initiate a US-Cuban rapprochement but no one doubted that, behind the scenes, Fidel remained el Jefe Maximo.

What would have happened with Fidel Castro alive and Donald Trump in the White House, we will now never know. The one thing certain is that it would have been interesting.

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz: born Birán, eastern Cuba, 13 August, 1926; died Havana, 25 November 2016.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments