El Salvador: Meet the former Marxist guerrilla fighting for reproductive rights in a country where there are none

Exclusive interview: Morena Herrera has suffered death threats and slander, but she will not stop

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.For more than a decade, Morena Herrera fought as a left-wing guerrilla against government forces in a war that left up to 70,000 people dead. Now, she is battling for women’s reproductive rights in a country with perhaps the poorest record of any nation.

There are a handful of countries that do not permit abortions under any circumstance - not for rape, incest or to protect the health of the mother - yet campaigners say that only in El Salvador is the law so aggressively pursued.

“The problem is the lack of awareness about what reproductive rights are, and because of this the [impression] for the majority of women is that they are here just to be mothers,” she recently told The Independent. “For example, right now, the huge number of teenage pregnancies is brutal. A third of all births come from teenage mothers.”

She added: “And there is another terrible number - those mothers who are beneath the age of 14.”

As the head of the Citizen’s Group for the Decriminalisation of Abortion since 2009, she is today often the only champion for such women, criminalised by the state. She has received death threats and abuse, and faced allegations that she is working for those who want to damage the country.

“There has been a slander campaign,” she said. “What worries me the most is when my family is caught in the middle of it and they get afraid. Or else my mother or daughter sees something on the news. They don’t want to go through the same fears they went through in the past.”

The spectre of fear is associated with the bitter civil war that took gripped the country between 1980 and 1992. During that conflict, Ms Herrera fought with the left-wing rebels of the Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front (FMLN) against a military-backed government supported by the United States. Since 2009, the FMLN has controlled the country’s presidency and there are some who are critical that it has not moved faster on women’s rights.

Asked if she was frustrated by the pace of change under a government controlled by her Marxist former colleagues, she said she hoped there would be progress before the current president, Salvador Sánchez Cerén, stands down in 2019. “My spirits never get disappointed,” she said.

The state of reproductive rights in El Salvador, a staunchly Catholic Central American country of around six million people, was not always so dire. Prior to 1998, abortion was permitted in cases of rape, incest, where a foetus was injured or if the life of the woman was in danger.

Yet that year, amid pressure from religious conservatives and the powerful church, the law was changed to remove any exceptions whatsoever. It is estimated that between 1998 and 2013, more than 600 women have been jailed for up to 40 years after being accused of having had an abortion. (In many of these cases, say activists, the women hadd simply endured a miscarriage.)

Ms Herrera and her colleagues have fought for a group of jailed women known as “las 17”. A handful have been freed, but the authorities keep prosecuting more women; the so-called "17" now stands at 25.

“It’s because the reproductive rights of women are not recognised,” she said, trying to explain the slow pace of change. “They are fearful. They fear the response of the church and other organisations. We also have a very strong influence from the media.”

The plight of women fighting for control over their bodies made international headlines in 2013. A young woman, at the time identified only a Beatriz, suffering from lupus and several months pregnant with her second child, was told that the foetus was diagnosed with anencephaly, meaning it would be born without part of the brain and could not survive.

Doctors determined that her own medical condition made carrying the baby to term a threat to Beatriz’s life. Her case was appealed all the way to the country’s Supreme Court, which ruled doctors could not terminate her pregnancy. Eventually, as her health became ever more precarious, she was given a caesarean section when the foetus was 27 weeks. The baby lived for five hours.

Such threats to women's health are not uncommon. Experts say doctors are forced to stand by and watch as women come into their clinics with ectopic pregnancies, fearing for their lives. Under the country’s rules, a physician cannot operate to save the mother until it is determined the foetus is dead.

One doctor who quit her job with a government hospital now runs her own clinic, where she estimates she has helped two dozen women terminate their pregnancies. For this, she said, she could be jailed for up to 12 years if the authorities found out, but she said she must help women in need.

“When I was a medical student I was told that we did not need to call the police because if a person thought that was going to happen, they would not come to the hospital,” she said. “Many of the women don’t have access to contraception or else it does not work.”

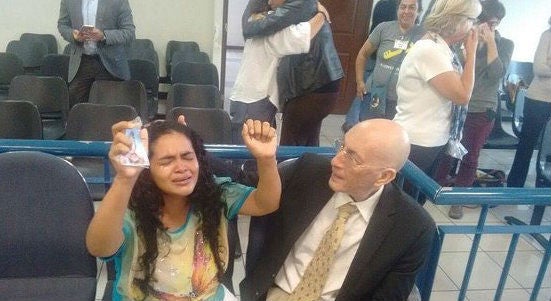

Ms Herrera said the fight to try and persuade judges to think humanely was difficult work. (Recently, the group celebrated a rare, happy victory when woman who had been jailed for 40 years, Maria Teresa Rivera, was freed after spending five years behind bars.)

“Woman are accused and go through all of this for no reason. We see the judges give these sentences and it reflects deep ignorance. It’s hard to reverse these decisions,” she said.

“These women rot in jail. They cannot see how important it is to provide sex education. Twelve-year-olds are not ready to become mothers.”

Ms Herrera has many opponents in El Salvador. The Yes to Life Foundation, which work closely with the church, has a high public profile and fights to resist loosening of the abortion laws.

“Life is sacred – you don’t have the right to kill someone because someone else will suffer. We leave this decision to God,” the group’s president, Carla de la Cayo, told the Globe and Mail newspaper.

Ms Herrera has also been accused of harming El Salvador’s reputation and of accepting money from outside group.

“I cannot deny that we have a lot of international support, but we get this because we apply for it. Yet we also have a lot of national support,” she said. “We have enough challenges as a society to look for help.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments