Peaches Geldof, drug addiction, and a very brief history of heroin

How the drug originally marketed as a cough medicine became one of the most addictive recreational habits of our times

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Rarely have public sympathies towards an individual changed quite so dramatically as when heroin was ruled to be a "likey cause" of Peaches Geldof's death at her preliminary inquest in April.

This led many to question why a millionaire mother-of-two with a self-professed “perfect life” and every chance at a successful future had turned to the Class A drug - ordinarily associated with those who, under emotional and environmental strain, reject society's goals and institutionalised means of achieving them - in order to get by.

Some cited the inner sense of sadness that she continued to live with following the death of her mother, Paula Yates, in 2000. Some said that she became dependent, and had regularly attended rehabilitation appointments, unbeknown to her “straight, family man” husband, Thomas Cohen. Others, that in a particularly low moment, she’d rekindled her relationship with an old demon and simply misjudged the strength; her tolerance levels lowered after months of abstinence.

Following her full inquest, which took place on 23 July 2014, we now know that these initial reports were, in fact, correct.

Giving evidence in the Coroners Court in Gravesend, Kent her surviving husband,Thomas Cohen, described his late wife as an “addict” and confirmed that she had been on a two-year rehabilitation programme.

He said that she had weekly drugs tests that she reported to be clean. He told the coroner he now believes she lied about the results of her tests.

Citing a strength of 61 per cent purity (normal street grade heroin is around 32 per cent pure), the coroner Roger Hatch also concluded that Peaches’ tolerance levels had significantly declined over time.

“Someone who stops or ceases to use heroin then resumes is less able to tolerate the levels they previously had,” he said in summary.

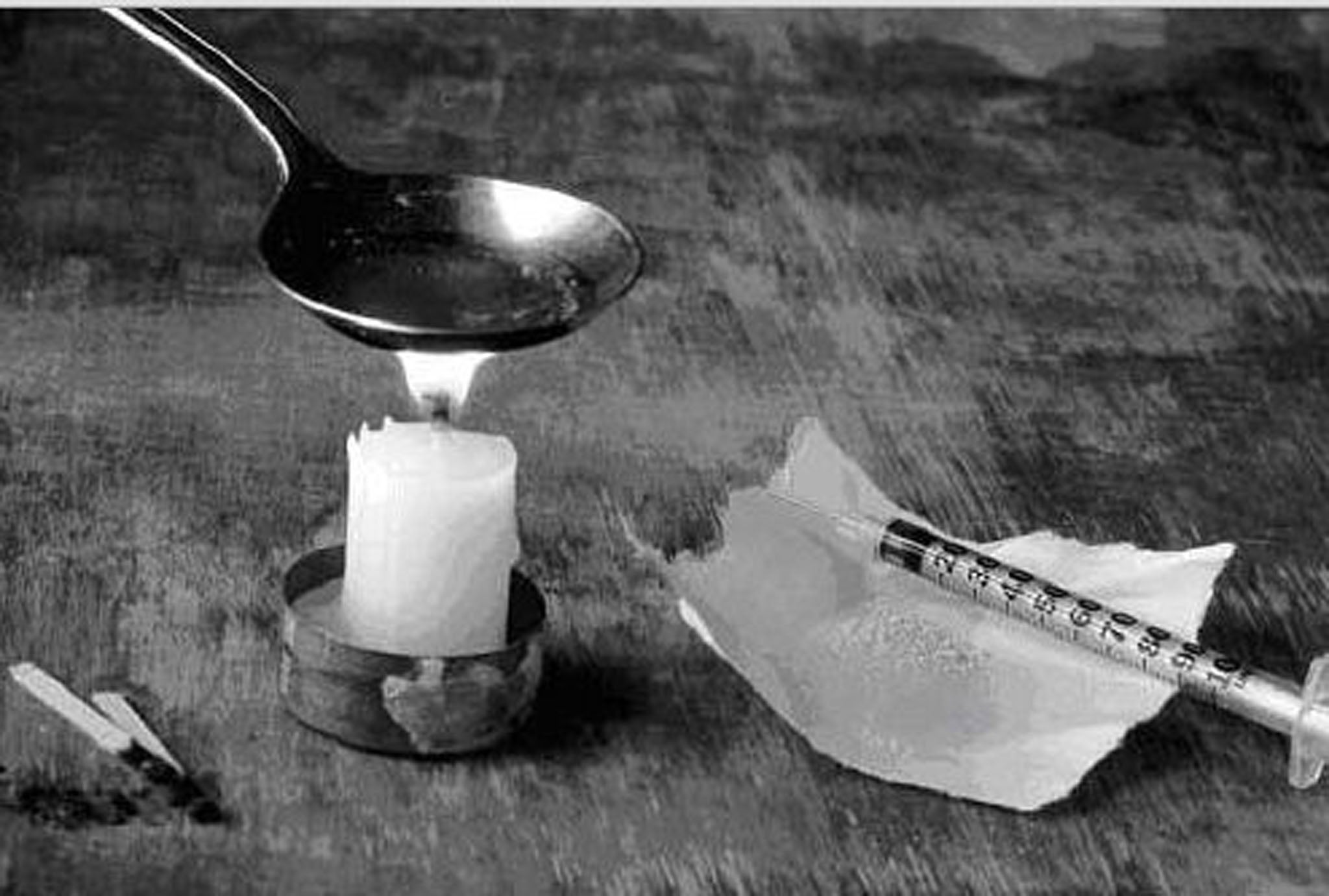

Many reacted to the details of her final moments, like the capped syringe found hidden in a box of sweets by her body, with disbelief. But regardless of her position, Peaches was no different to any other addict: all of the above is entirely characteristic of anyone dependent on heroin.

Users have described an intense, pleasurable rush and an acute transcendent state of euphoria after the Class A substance, which occurs after diacetylmorphine – heroin’s chemical name – is metabolised into morphine in the brain. That sense of escapism and dulling of physical and emotional pain goes some way to explaining why anyone would choose to experiment with the highly addictive drug in the first place.

“I cannot accurately convey the efficiency of heroin in neutralising pain,” rehabilitation campaigner Russell Brand wrote in an article for The Spectator last year. He was writing following the death of his friend, Amy Winehouse, herself a heroin addict. “It transforms a tight white fist into a gentle brown wave, and from my first inhalation 15 years ago it fumigated my private hell.”

Far from its ‘one shot kills all’ reputation, there are actually very few long-term biological complications caused by unadulterated heroin use, other than dependency and constipation. The trouble arises with the purity of the drug – estimated to be between 30% and 50% at street level in the UK – and the way it can be administered.

Intravenous use, for example, is riddled with risks. Contracting blood-borne pathogens like HIV, bacterial infections, abscesses and more could all affect those using and sharing needles. Meanwhile, the likelihood of overdose is significantly raised in those returning to heroin after a period of avoidance. Tolerance decreases over time, occasionally leading those relapsing to overestimate the amount needed to achieve the desired, previous effect. Fatalities are often caused by those combining Heroin with other depressant drugs, like alcohol or Valium.

And then there are the harrowing consequences of attempting to come off the drug – the agonising withdrawals, the sweating, the vomiting and hallucinations. Oh, and the loss of friends, family, careers, and the inability to care for anyone, or about anything, least of all yourself.

Needless to say, the latter has rightly transformed the reputation of heroin – one of the few street drugs still known by its initial brand name – from a terribly embarrassing chemical blunder first made by a German pharmaceutical company in the 1800s, to one of the most controversial narcotics in modern times.

So, as it slowly edges its way back into popular use, riding on a tidal wave of 90s revivalism, take a very brief look at its history, from over-the-counter cough medicine to illegal killer:

Heroin – the chemical name for which is diacetylmorphine – was originally synthesized by British chemist C.R.Alder Wright (pictured below) in 1874, by adding two acetyl groups to the molecule morphine, which is naturally found in the opium poppy.

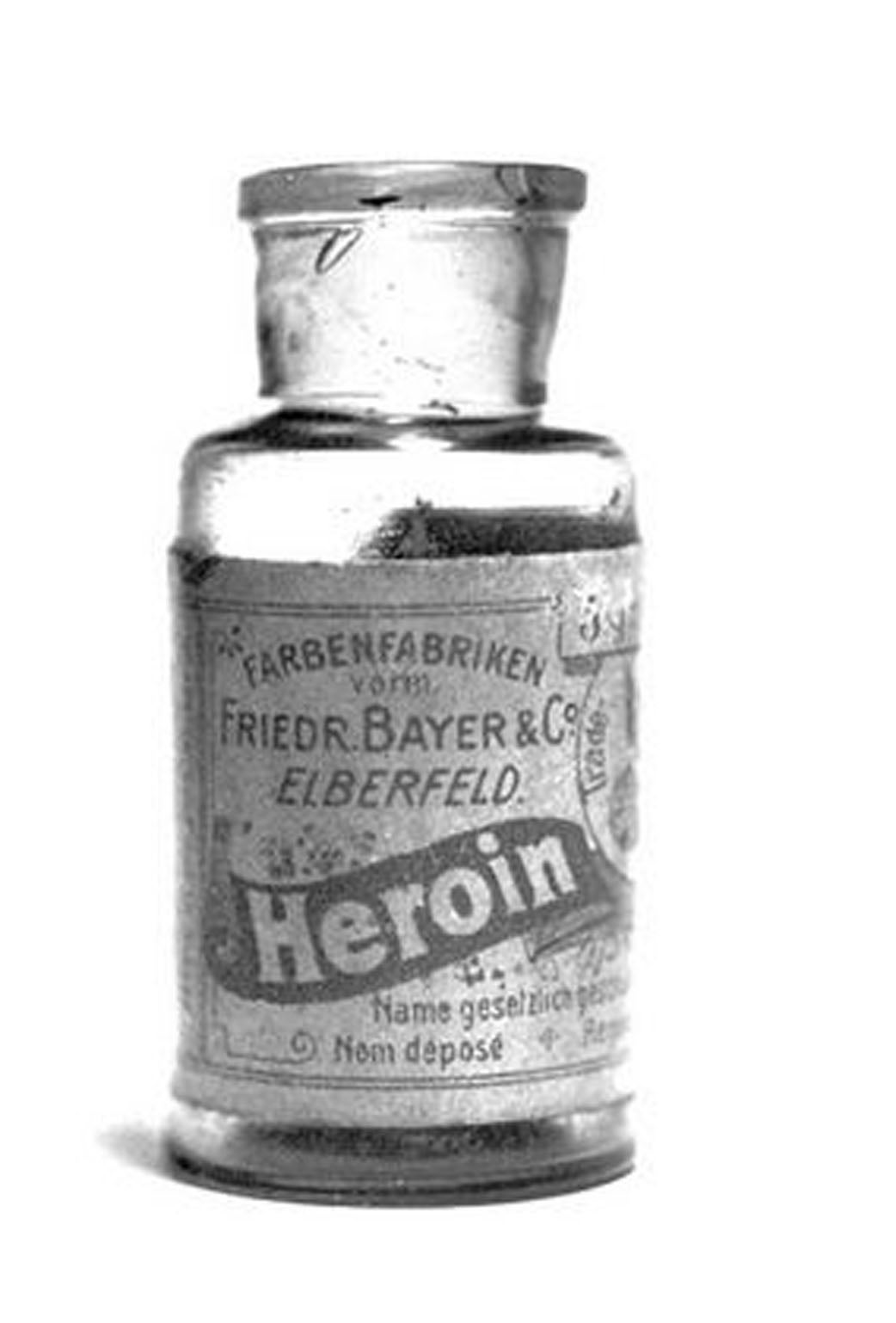

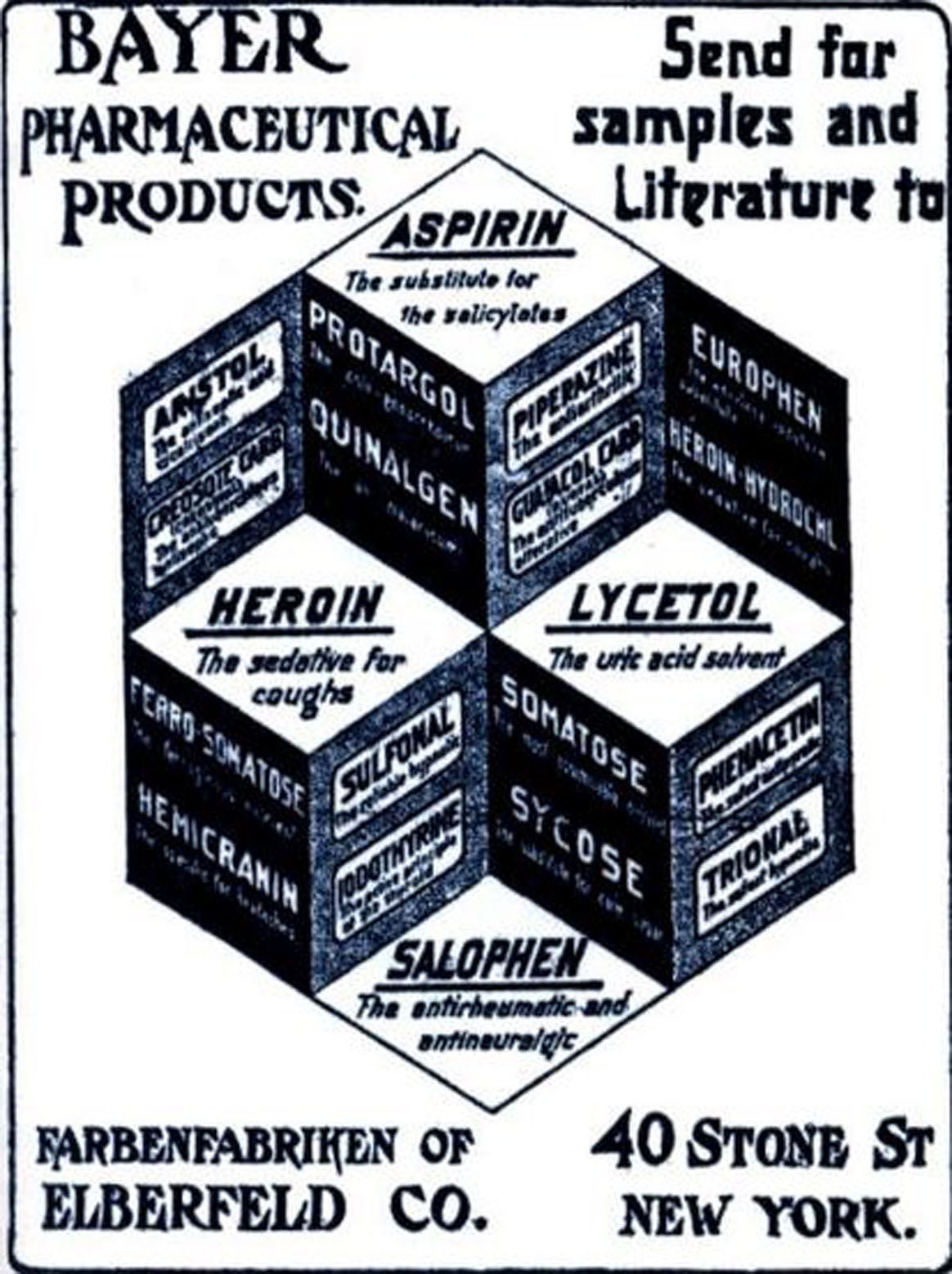

Bayer, the German pharmaceutical company behind Alka-Seltzer and Aspirin, bought the rights to diacetylmorphine, marketing it under the name “Heroin” in 1895 because early testers said that it made them feel “heroisch” or “heroic”.

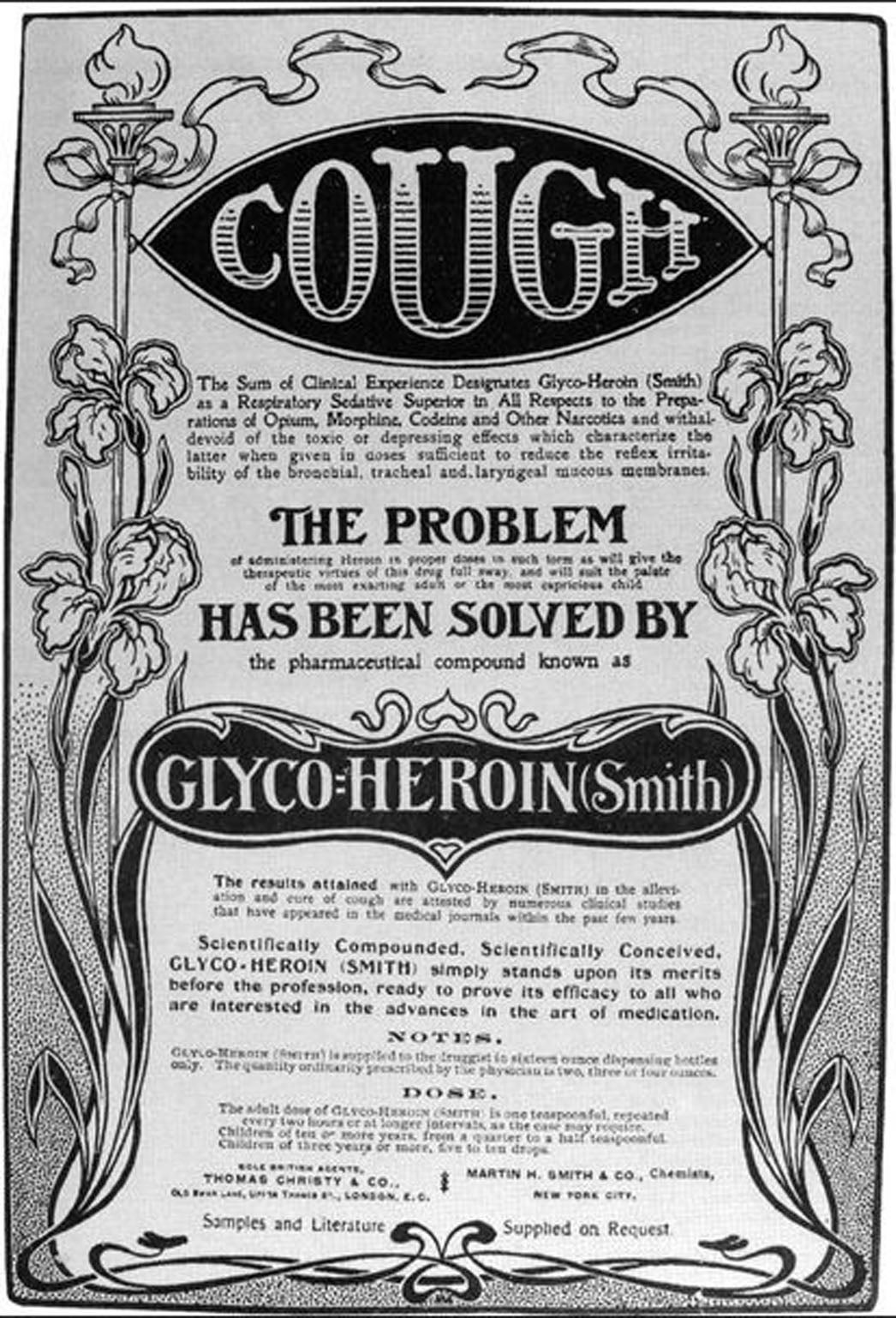

By 1898, it was ready for mass marketing. It was originally sold as an over-the-counter cough suppressant that didn’t have problematic side effects, like addiction (the irony) - while alternative treatments morphine and codeine did. This was before they realised that, when taken into the body, it actually converts into morphine, and is ferociously addictive. Thus defeating the object and defining what was to become a historically embarrassing moment for the company in later years.

In 1899, Bayer was producing over a ton of Heroin and exporting the drug to 23 countries, while free samples sent to doctors and studies appeared in medical journals. It was also around this time that early reports of addiction began to surface. The company wisely released Aspirin the same year, a non-addictive alternative that would go on to become one of the most popular and widely used pain relief drugs in the world.

US medicines containing heroin were available over the counter from 1907, after the American Medical Association gave it its stamp of approval.

In 1914, as dependency became a torrent and overdoses began to be reported with greater frequency, heroin was made illegal to obtain without a prescription from a doctor in the US. Bayer lost some of its trademark rights to heroin and Aspirin under the Treaty Of Versailles in 1919, after the German defeat in World War I.

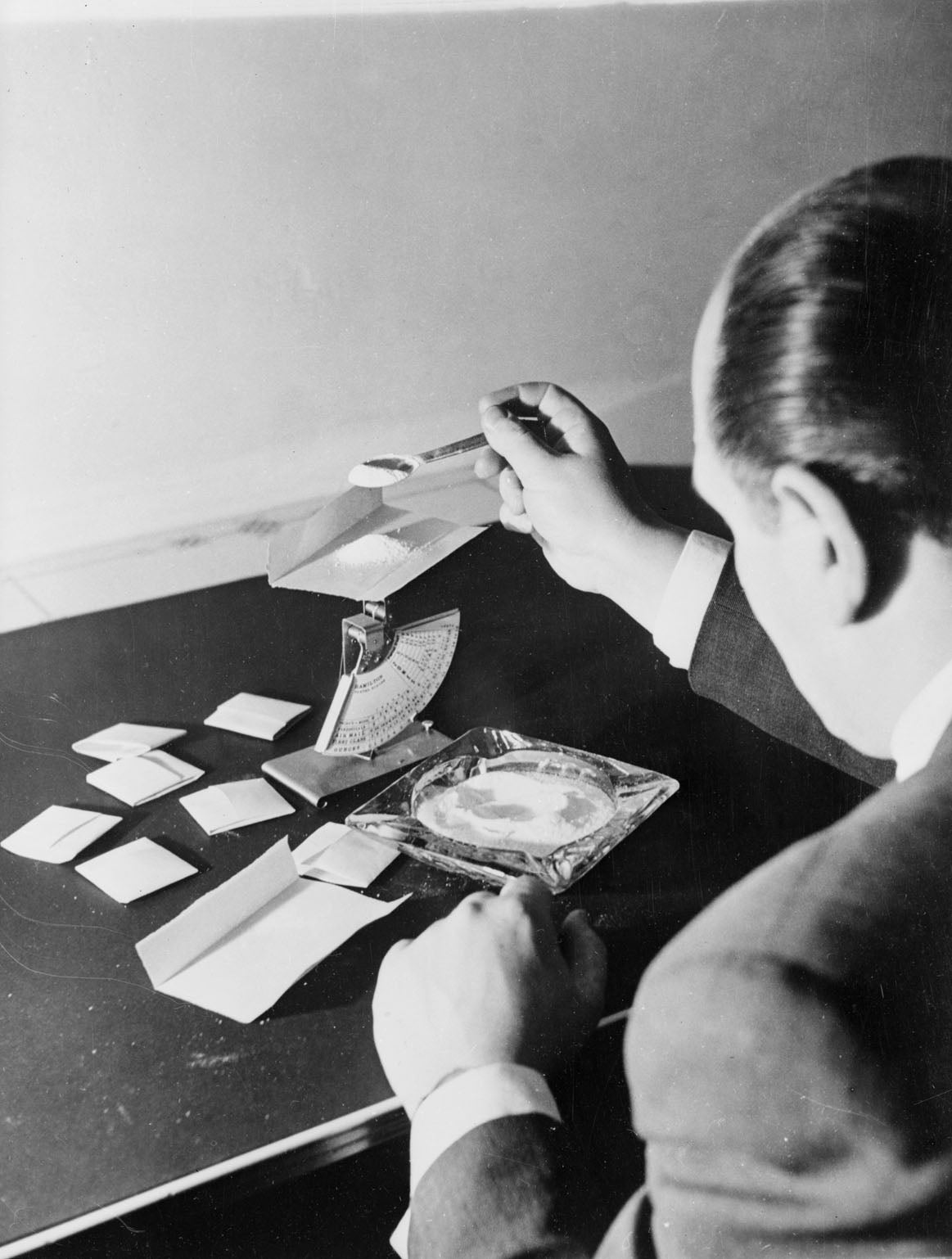

In the early 1920s, a number of addicted users in New York supported themselves by collecting and selling scrap metal retrieved from industrial dumps. It was from this that the label “junkies” was born.The behavior of heroin addicts was soon, however, to cause a concern to the public and the authorities. In 1924, it became completely illegal, and doctors were told they could no longer prescribe the drug.

By this point, heroin had become popular among creative industries. Pictured below is famed actress Jeanne Eagels, who died of a Heroin overdose in 1929. Its outlawed use had pushed manufacturers underground, and the purity of the product illegal traders now used varied in quality, though were plentifully supplied by still functioning and legal chemical companies in western Europe.

In the UK, the Rolleston Committee Report in 1926 made heroin illegal and ruled that dealers were to be prosecuted, but doctors could prescribe diacetylmorphine to users when they were withdrawing from it, if it would cause harm or severe distress to the patient to go without it. This would be the law until 1959 when the number of diacetylmorphine addicts doubled every 16 months between 1959 and 1968.

The Brain Committee recommended that only selected, specially approved doctors at specialised centres were allowed to prescribe diacetylmorphine to users in 1964. The law was further restricted in 1968, and by the 1970s, the emphasis shifted to encouraging abstinence and the use of substitute methadone.

In the 1980s, the UK experienced a surge in heroin supply because of a sudden cheap influx from Pakistan (the main supplier had been – and is now – Afghanistan). Cues from popular culture – and a social downtown caused by the economic and industrial crisis in the late 1970s – created the perfect environment for the Trainspotting generation.

In the 1990s, heroin use was again popularized by the rise of grunge and Britpop, while the emergence of ‘the waif’ in fashion, of which Kate Moss is often cited as the originator, would give rise to the term ‘heroin chic’.

In 1994, the Swiss began to trial a diamorphine maintenance program for users who had failed multiple withdrawal programs. It aimed to maintain the health of the user, by discouraging the use of illicit street Heroin. It was deemed a success.

Today, the largest producer of opium, needed to create heroin is Afghanistan. This is closely followed by Mexico, who, it is it estimated, increased their rate of production sixfold between 2007 and 2011. Diacetylmorphine is a controlled, Class A substance in the UK, but continues to be used in palliative care for the treatment of acute pain, such as in severe physical trauma, post-surgical and chronic pain, as well as relieving sufferers of terminal illnesses.

Key figures continue to campaign for greater sympathies and better treatment of heroin addicts as they attempt to rehabilitate themselves and re-enter society. Russell Brand’s Give it Up Fund, run in conjunction with Comic Relief, aims to provide financial aid to help people remain free from substance abuse by setting up support groups. "It's integral that people entering a life of abstinence after the chaos of addiction have stability, support and a role to play in the wider community," he said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments