Donald Trump: What the tycoon was up to when John McCain was a prisoner of war in Vietnam

Trump said of McCain's military service: 'I like people that weren’t captured'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It was the spring of 1968 and Donald Trump had it good.

He was 21 years old and handsome with a full head of hair. The Vietnam War draft passed him by on his way to earning an Ivy League degree. He was fond of fancy dinners, beautiful women and outrageous clubs. Most important, he had a job in his father’s real estate company and a brain bursting with money-making ideas that would make him a billionaire.

“When I graduated from college, I had a net worth of perhaps $200,000,” he said in his 1987 autobiography “Trump: The Art of the Deal,” written with Tony Schwartz. (That’s about $1.4 million in 2015 dollars.) “I had my eye on Manhattan.”

More than 8,000 miles away, John McCain sat in a tiny, squalid North Vietnamese prison cell. The Navy pilot’s body was broken from a plane crash, starvation, botched operations and months of torture.

As Trump was preparing to take Manhattan, McCain was trying to relearn how to walk.

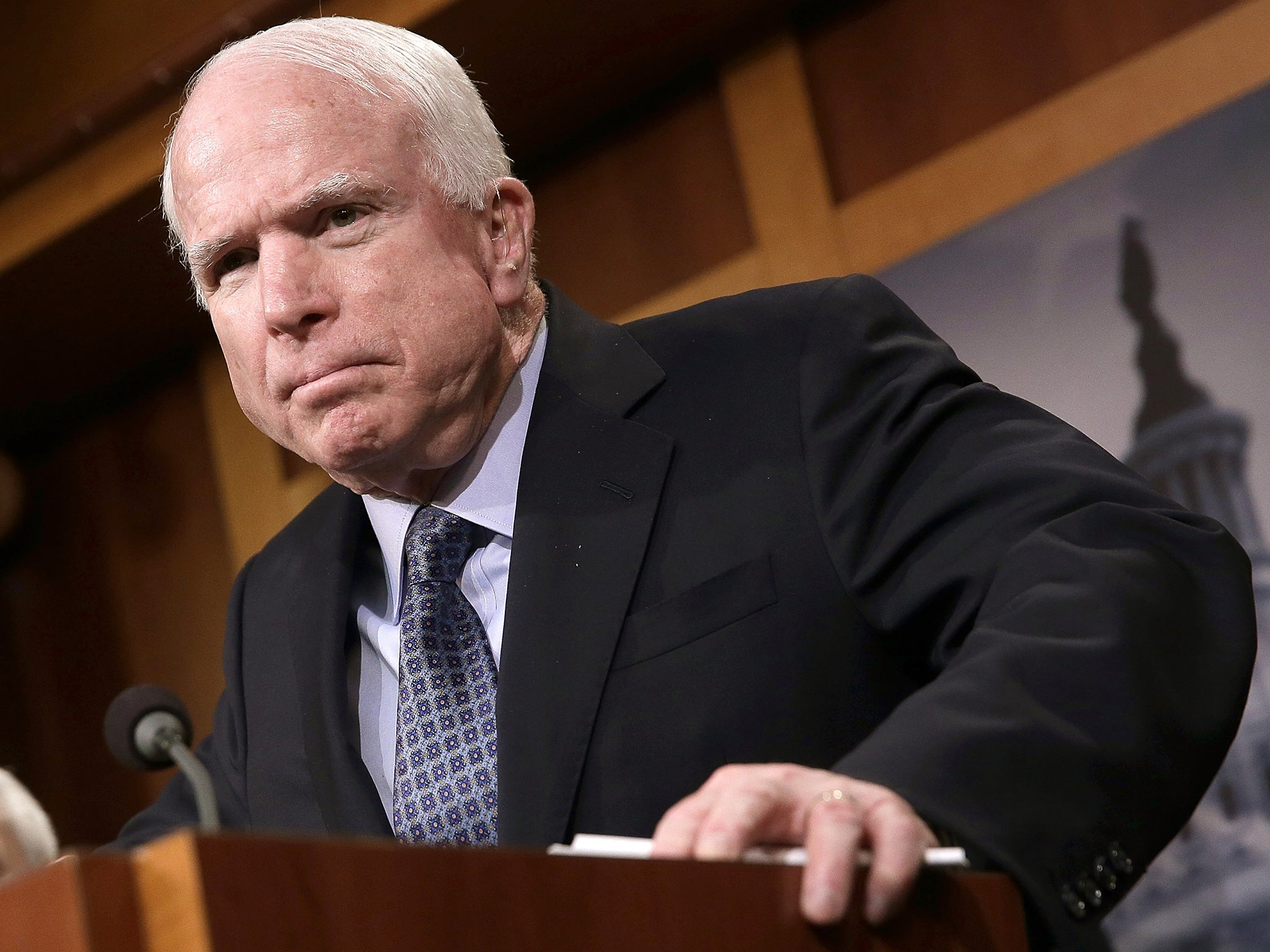

The stark contrast in their fortunes was thrown into sharp relief Saturday when Trump belittled McCain during a campaign speech in Iowa.

“He’s not a war hero,” Trump said of McCain.

“He’s a war hero because he was captured,” Trump said sarcastically. “I like people that weren’t captured.”

Trump’s comments drew scorn from his fellow Republican presidential contenders. But The Donald didn’t back down.

“When I left the room, it was a total standing ovation,” he told ABC News in reference to his already infamous Iowa speech. “It was wonderful to see. Nobody was insulted.”

In fact, a lot of people were insulted.

“John McCain is a hero, a man of grit and guts and character personified,” Secretary of State John Kerry said in a statement. “He served and bled and endured unspeakable acts of torture. His captors broke his bones, but they couldn’t break his spirit, which is why he refused early release when he had the chance. That’s heroism, pure and simple, and it is unimpeachable.”

Watch Trump's remarks here:

If The Donald doesn’t think that that’s heroic, then what, exactly, is admirable in his eyes?

And what was he doing while McCain was locked up in a jungle dungeon?

The answer reveals deep divides in the two men’s lives and claims to leadership. They may similarly embrace free enterprise, but when it comes to character, the two GOP presidential hopefuls could hardly be more different.

McCain famously followed his father and grandfather — both admirals — into the Navy. He has said his role model was Teddy Roosevelt, the barrel-chested, bear-hunting war hero turned conservative president. He also saw his grandfather and father as heroes too, as he wrote in his autobiography, “Faith of My Fathers.”

“My grandfather was a naval aviator, my father a submariner. They were my first heroes, and earning their respect has been the most lasting ambition of my life.”

Growing up in Queens, The Donald’s role models were more … theatrical.

“Two of the people I admired most and who I kind of studied for the way they did things were the great Flo Ziegfeld, the Broadway producer, and Bill Zeckendorf, the builder,” he told the New York Times in 1984. “They created glamour, and the pageantry, the elegance, the joy they brought to what they did was magnificent.”

McCain grew up in a military household. Trump grew up in a home dominated by his hard-charging, penny-pinching businessman father.

Both young men had rebellious streaks. At the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis, McCain was known as a “tough, mean little f——” who “was defiant and flouted the rules” but never enough to get kicked out, according to Robert Timberg’s “The Nightingale’s Song.”

McCain enlisted in the Navy in 1958. Around the same time, Trump was sent to the New York Military Academy to straighten him out after his own youthful transgressions. ”He was a pretty rough fellow when he was small,” his father told the Times in 1983.

But the similarities stopped there. Despite a successful stint at the military school, Trump was not selected to enlist. It was 1964 and the Vietnam War was escalating.

He considered going to film school in California. “I was attracted to the glamour of the movies,” he said in “Trump: The Art of the Deal,” adding that he “admired” Hollywood’s “great showmen. But in the end I decided real estate was a much better business.”

Instead Trump attended Fordham for two years before transferring to the University of Pennsylvania, where he took economics courses at its famed Wharton School.

During his time in school, Trump received four student deferments from the draft.

“If I would have gotten a low [draft] number, I would have been drafted. I would have proudly served,” he told ABC News. “But I got a number, I think it was 356. That’s right at the very end. And they didn’t get — I don’t believe — past even 300, so I was — I was not chosen because of the fact that I had a very high lottery number.”

As Trump was enjoying the Ivy League and avoiding the war, John McCain was about to become one of its most high-profile casualties.

The lieutenant commander had been flying for months, conducting targeted strikes on North Vietnam. He had already been injured in an aircraft carrier fire that killed 134 fellow sailors. And he had already made a name for himself as a pilot.

On Oct. 25, 1967, McCain had destroyed two enemy MiG fighter planes parked on a runway outside Hanoi. He begged to go out the next day, too.

But as he flew into Hanoi again on Oct. 26, his jet’s warning lights began to flash.

“I was on my 23rd mission, flying right over the heart of Hanoi in a dive at about 4,500 feet, when a Russian missile the size of a telephone pole came up — the sky was full of them — and blew the right wing off my Skyhawk dive bomber,” he wrote in a 1973 account of his ordeal. “It went into an inverted, a most straight-down spin. I pulled the ejection handle, and was knocked unconscious by the force of the ejection.”

McCain regained consciousness when his parachute landed him in a lake. The explosion had shattered both arms and one of his legs. With 50 pounds of gear on him and one good limb, he struggled to swim to the surface.

North Vietnamese dragged him to shore. Then stripped him to his underwear and began “hollering and screaming and cursing and spitting and kicking at me.”

“One of them slammed a rifle butt down on my shoulder, and smashed it pretty badly,” he wrote. “Another stuck a bayonet in my foot. The mob was really getting up-tight.”

He was interrogated for four days, losing consciousness as his captors tried to beat information out of him. But he refused.

As the voluble Trump was already making a name for himself sweet-talking deals for his dad’s real estate developing company, McCain was clamming up in his filthy prison camp.

And as Trump drove around Manhattan in his father’s limo, McCain was refusing to mention his dad for fear of handing valuable intelligence to the enemy.

McCain might have died from his injuries had the North Vietnamese not found out on their own that his father was an admiral. Instead, they moved him to a hospital and performed several botched operations on him. They sliced his knee ligaments by accident and couldn’t manage to set his bones.

“They had great difficulty putting the bones together, because my arm was broken in three places and there were two floating bones,” he wrote. “I watched the guy try to manipulate it for about an hour and a half trying to get all the bones lined up. This was without benefit of Novocain.”

That Christmas, as Donald Trump was celebrating the holiday with his family, McCain was starving to death in a prison camp called “The Plantation.”

“I was down to about 100 pounds from my normal weight of 155,” he wrote. “I was told later on by [cellmate] Major Day that they didn’t expect me to live a week.”

McCain survived, however, slowly regaining his strength. By the spring of 1968, he had taught himself to walk again. Not that there was anywhere to walk. He was in solitary confinement inside a hot, stifling, windowless cell.

Trump, meanwhile, was taking Manhattan by storm. He had already made a small fortune — $200,000 then is almost $1.4 million today — working for his father during college.

In his autobiography, Trump describes these early years as fraught with danger: a quick learning curve for the soon-to-be-celebrity CEO as he went around learning the business. “This was not a world I found very attractive,” he wrote in “Trump: The Art of the Deal.”

“I’d just graduated from Wharton, and suddenly here I was in a scene that was violent at worst and unpleasant at best.”

The danger? Collecting rent.

“One of the first tricks I learned was that you never stand in front of someone’s door when you knock. Instead you stand by the wall and reach over to knock,” Trump wrote of collecting for his father, who owned low-income housing blocks. “The first time a collector explained that to me I couldn’t imagine what he was talking about. ‘What’s the point,’ I said. The point, he said, is that if you stand to the side, the only thing exposed to danger is your hand.”

“There were tenants who’d throw their garbage out the window, because it was easier than putting it in the incinerator,” he wrote in horror.

Meanwhile, McCain languished in a genuine hell. When he wasn’t being tortured — several times his interrogators re-broke his mended bones — he was battling everything from dysentery to hemorrhoids.

The prisoner of war survived on watery pumpkin soup and scraps of bread. He saw several fellow prisoners beaten to death, yet McCain refused to sign the confession that would have granted him a speedy release (and a publicity coup to the North Vietnamese).

Trump was living large — maybe not by today’s Trump standards but larger than most Americans. He ate in New York City’s finest restaurants, rode in his father’s limousines and began hitting the clubs with beautiful women.

“The turning point came in 1971, when I decided to rent a Manhattan apartment,” he wrote. “It was a studio, in a building on Third Avenue and 75th Street, and it looked out on the water tank in the court of the adjacent building. ….I was a kid from Queens who worked in Brooklyn, and suddenly I had an apartment on the Upper East Side. …. I got to know all the good properties. I became a city guy instead of a kid from the boroughs. As far as I was concerned, I had the best of all worlds. I was young, and I had a lot of energy.”

That energy went into signing some of his first real estate deals — and into partying.

“One of the first things I did was join Le Club, which at the time was the hottest club in the city and perhaps the most exclusive–like Studio 54 at its height,” he wrote. “Its membership included some of the most successful men and the most beautiful women in the world. It was the sort of place where you were likely to see a wealthy seventy-five-year old guy walk in with three blondes from Sweden.

“It turned out to be a great move for me, socially and professionally. I met a lot of beautiful young single women, and I went out almost every night,” he added. “Actually, I never got involved with any of them very seriously. These were beautiful women, but many of them couldn’t carry on a normal conversation.”

He was so good looking he said, that the manager of the club “was worried that I might be tempted to try to steal their wives. He asked me to promise that I wouldn’t do that.”

As McCain remained in solitary confinement, tapping messages on the filthy walls to his fellow POWs in Morse code, Trump was out partying at legendary nightclubs.

Several years later, The Donald was frequenting “Studio 54 in the disco’s heyday and he said he thought it was paradise,” Timothy O’Brien wrote in “TrumpNation: The Art of Being the Donald.” “His prowling gear at the time included a burgundy suit with matching patent-leather shoes,” O’Brien wrote.

“’I saw things happening there that to this day, I have never seen again,'” Trump told O’Brien. “‘I would watch supermodels getting screwed, well-known supermodels getting screwed on a bench in the middle of the room. There were seven of them and each one was getting screwed by a different guy. This was in the middle of the room.’”

As Trump made plans to buy and refurbish bankrupt hotels, McCain was staving off death in a prison dubbed “The Hanoi Hilton.”

And as McCain continued to refuse special treatment, The Donald actively courted it.

“The other thing I promoted was our relationship with politicians, such as Abraham Beame, who was elected mayor of New York in November of 1973,” he wrote in “Trump: The Art of the Deal.” “Like all developers, my father and I contributed money to Beame, and to other politicians. The simple fact is that contributing money to politicians is very standard and accepted for a New York City developer.”

McCain refused to meet with most visitors for fear of being used as a puppet by the North Vietnamese. But back in the U.S., Trump was too eager to manipulate the press.

“At one point, when I was hyping my plans to the press but in reality getting nowhere, a big New York real estate guy told one of my close friends. ‘Trump has a great line of s–t, but where are the bricks and mortar?’” he wrote. “I remember being outraged when I heard that.” (Expletive deleted by the Washington Post not by Trump.)

If Trump was used to dining well, the only decent meal McCain had during his five years in prison was the night before he was released.

It was March 14, 1973. McCain arrived back in America a physically broken man, but also a hero.

That word has yet to be applied to Trump.

That same year, the Department of Justice slapped the Trump Organization with a major discrimination suit for violating the Fair Housing Act.

“The Government contended that Trump Management had refused to rent or negotiate rentals ‘because of race and color,” according to the New York Times. “It also charged that the company had required different rental terms and conditions because of race and that it had misrepresented to blacks that apartments were not available.”

Trump at first resisted signing a consent decree, according to the Times. He hired his friend, Roy Cohn, the lawyer and former right hand man to U.S. Sen. Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin. “Mr Trump said he would not sign such a decree because it would be unfair to his other tenants,” the Times reported. “He also said that if he allowed welfare clients into his apartments … there would be a massive fleeing from the city of not only our tenants but the communities as a whole.”

But ultimately the company came to terms with the government.

Trump would weather the scandal, of course, and go one to build his fortune to its present day tally of $4 billion.

McCain, in contrast, received a Silver Star, Bronze Star, Purple Heart and Distinguished Flying Cross. He would become a U.S. Senator and nearly become president.

Whether Trump can triumph where McCain came up short remains to be seen.

©Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments