David Bowie: From Bromley to New York – the places that shaped the man

He was happy to perform in the guise of extravagant stage personae, but offstage Bowie was far harder to pin down

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The whole world knew David Bowie. Far fewer, however, knew David Jones. While he was happy to take to the stage in the guise of such extravagant stage personae as Ziggy Stardust, offstage, David Bowie was far harder to pin down. Which, it seems, is how he preferred it. In the first flush of his fame, he admitted to preferring “dressing up as Ziggy to being David”.

In later life, it was said, he had stopped using the name Bowie in preference for the unimprovably anonymous David Jones, the name that this perpetual music revolutionary was given when born into apparent suburban normality in 1947.

Moving to the south-east London suburb of Bromley aged six, at first glance he appears to have enjoyed the archetypal suburban life: Bromley Technical High School for Boys, one O-level (in art), and then joining the Nevin D Hirst Advertising Agency as a trainee commercial artist in 1963.

Already, though, a far more challenging artist was being formed. Bowie’s half-brother, Terry Burns – so idolised that even after some of his early hits Bowie would introduce himself as “Terry’s brother” – taught him about jazz, Tibetan Buddhism, and, more tragically, human complexity. Terry, who in 1985 would take his own life, was schizophrenic, and it is hard not to see the ghost of the older brother in some of Bowie’s later references to the condition.

Less tinged with sadness were his visits in the late 1960s to the London Dance Studio, where he came under the tutelage of the dancer Lindsay Kemp, who, as well as becoming his lover, immersed him in theatricality in all its forms, from mime to commedia dell’arte. “It was everything I thought bohemia probably was,” he later recalled. “I joined the circus.”

Coveniently, he had, by this time, already left the ad agency. And so in the spring of 1969, it was a precociously artistically aware 22-year-old who found himself lodging in the conservative suburb of Beckenham, while composing the convention-shattering “Space Oddity”.

By the time the song gave him his first hit, he was in love with the woman who would become his first wife: Angie Barnett, a 19-year-old art student, an American with an upbringing far removed from Bowie’s own suburban background: raised in Cyprus, attending a Swiss finishing school, and – like Bowie – bisexual. Living with her, Bowie would later say, was like “living with a blow torch” – a remark that seemed aptly to sum up both the love affair’s passion and a tempestuousness that would lead to acrimonious divorce in 1980.

The success of “Space Oddity” led to Bowie touring the US, flirting with androgyny by wearing a dress in interviews and in the street, and being influenced by Iggy Pop and Lou Reed.

Then, in 1972, came Ziggy Stardust, the Spiders from Mars stage show, and an almost cult-like following for Bowie. His marriage now “open”, Bowie was now living the rock’n’roll lifestyle, in which – despite the arrival of his son Zowie in 1971 – drugs and sex played leading roles. In Los Angeles, the skeletal Bowie was said to have subsisted on milk, cocaine, and four packs of Gitanes a day.

Paranoia set in, as did a bizarre flirtation with fascism. He was, by his own later admission, “crazed”. In one particularly rambling, and deeply regretted interview, he suggested that “Adolf Hitler was one of the first rock stars”.

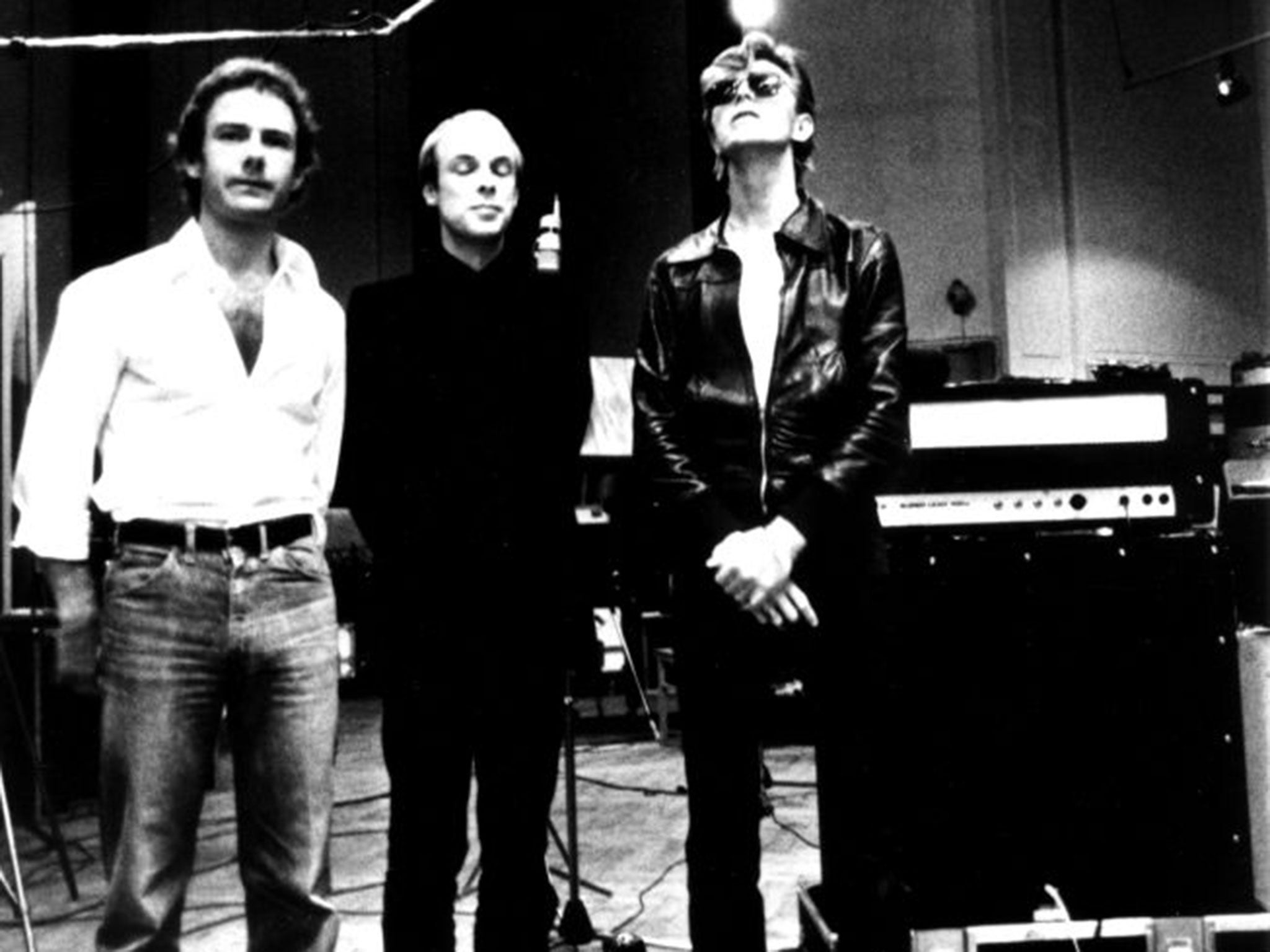

His move to Berlin in 1976 was motivated not just by artistic curiosity about the emerging Krautrock music movement, but by a need to find a healthier, humbler, and perhaps less artificial way of life. “I thought I’d take all that stagecraft,” he later said, “throw it all away and live the real thing.”

He grew a beard, painting and cycling his way round the city – while not completely renouncing his earlier, starrier existence. He was living opposite a car spare parts shop, but in an apartment where the upstairs neighbour was Iggy Pop, who would often pop down to visit.

Nor could he entirely escape his demons. Some reports suggest that if his cocaine use dropped in Berlin, his drinking increased.

If the artistic content of Bowie’s 1980s output has been less heralded by critics, the decade did signal a move towards stability and, perhaps, contentment. Finally, he got clean.

And then, in 1990, a mutual friend introduced him to the model Iman. “I was naming the children the night we met,” Bowie recalled. “It was absolutely immediate.” They married in Switzerland in April 1992, and later moved to New York, where, latterly, Bowie had been leading a life so withdrawn from the limelight that he attracted such tabloid epithets as “recluse”. It would be impossible, however, to equate such quietness with a star fading. It seemed very much a matter of choice. In 2000, the couple had a daughter, Alexandria, and having had a disrupted fatherhood with Zowie, Bowie, it seemed, wanted to maximise his time with “Lexi”.

Although there may have been little conventional about David Jones’ courtship of his supermodel wife – after the first date in Los Angeles, he reportedly had her Paris hotel room filled with gardenias – it seemed he found a true companion. One who knew, and appreciated David Jones as much as, if not more than Bowie. “I am not married to David Bowie,” she said. “I am married to David Jones. They are two totally different people.”

Nor did contentment ever extinguish Bowie’s creative spark. His final artistic contribution, the album Blackstar, was released last Friday. Already being favourably reviewed when news of his death emerged, the last track features Bowie singing: “I can’t give everything away.” As a person, perhaps he didn’t. As an artist, many would argue he gave everything.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments