Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.We are more connected today than at any time in our species’ history, yet isolated pockets of people still manage to live apart from globalized society.

It’s impossible to know exactly how many such tribes exist. Organisations like Survival International, however, estimate that more than 100 are sprinkled around the globe.

To call these people “uncontacted”, as they often are, is imprecise. It’s nearly impossible to completely avoid contact with outsiders, and even harder to avoid objects like factory-made knives or bowls that make their way deep into remote areas through trade.

Despite these connections, dozens of groups manage to preserve their isolation and ways of life.

Unfortunately, environmental destruction and exploitation – such as clearing forests for timber and farms – put many of these cultures at great risk. Survival International, the Brazilian government’s FUNAI (National Indian Foundation), and other advocacy groups seek to protect vulnerable tribes without interfering with them.

Here’s where some of these groups live and the challenges they face in preserving their unique existence.

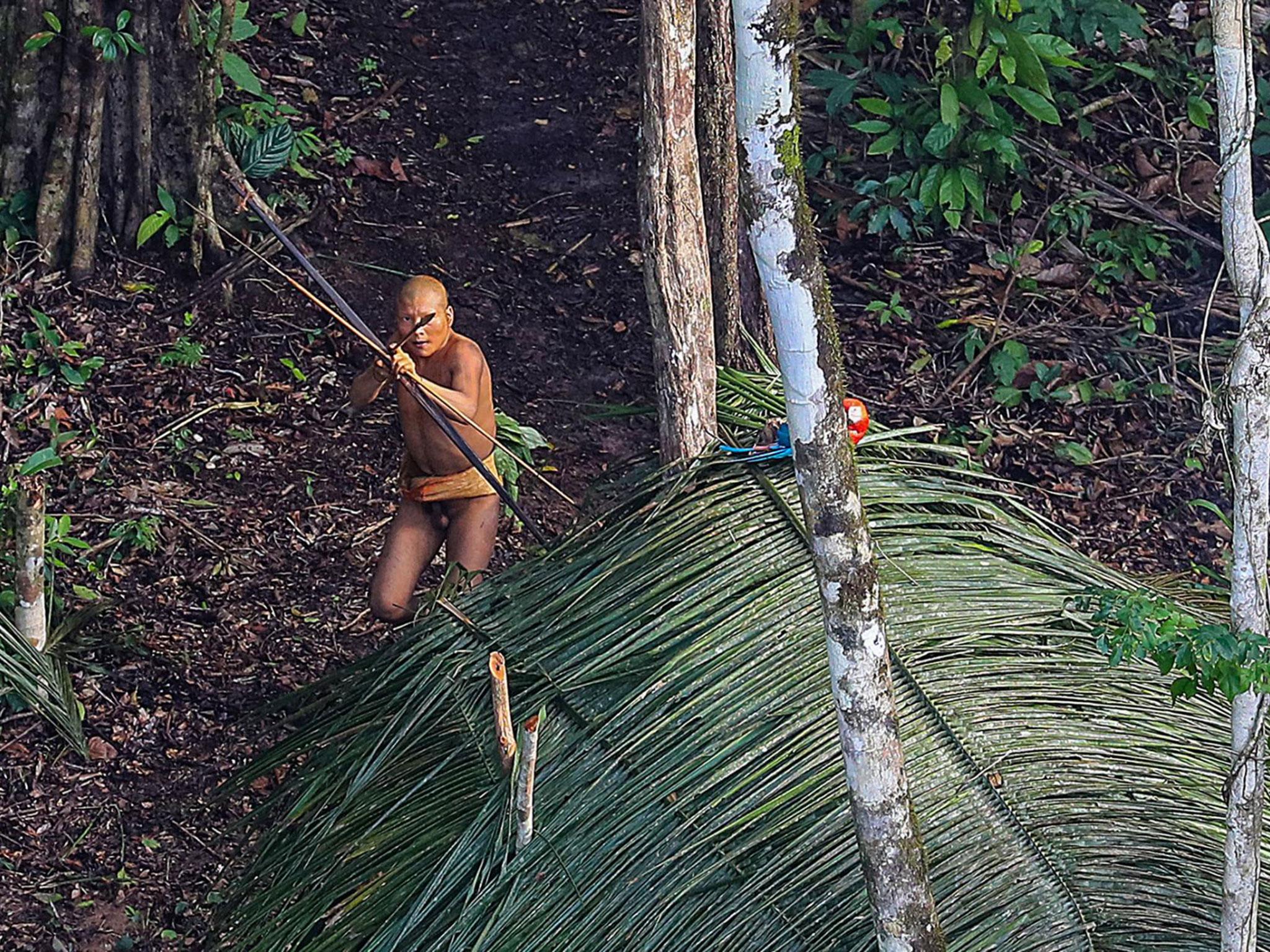

What does it mean to be uncontacted? The name’s a bit misleading – these are groups of people that have avoided, or even violently rejected, contact with the outside world. It’s possible they’ve made contact with outsiders at some point, but violence from settlers may have pushed them to return to isolation. Others may have never had an interest in the first place, championing their independence.

These tribes can avoid the outside world largely because of their geographic isolation in some of the most remote corners of the planet. Some live in the dense jungle highlands of New Guinea in Southeast Asia. The West Papua region in Indonesia is estimated to host more than 40 uncontacted groups. Verifying that number is difficult, however, because of the mountainous terrain and because journalists and human-rights organisations are banned from the region by the Indonesian government.

Others live in the Andaman Islands archipelago, between India and the Malay Peninsula. Until recently, the Jarawa of the Andaman Islands avoided contact with outsiders, although the Great Andaman Trunk Road has brought both tourists and poachers, leading to disease outbreaks and exploitation of the tribe. And just off the coast of the Andaman Islands is North Sentinel Island, home to the Sentinelese, a group that attacks just about anyone who comes ashore.

But most of the known uncontacted tribes live in South America, deep in the Amazon rainforest. Brazil claims to have most of the world’s uncontacted people, estimating as many as 77 tribes – though National Geographic estimates as many as 84. Many of them live in the western states of Mato Grosso, Rondonia, and Acre.

Illegal logging in the Amazon poses a huge risk for the indigenous people living in the region, and some uncontacted tribes have even come out of their isolation in protest of encroaching devastation.

The Brazilian government used to conduct “first contact” expeditions to find these tribes, believing that this was the best way to protect them. But they’ve since discontinued these expeditions in favour of the occasional status flyover. FUNAI seeks to protect these uncontacted tribes, as well as other indigenous people of the Amazon river basin, with infrequent flyovers, checking to see if they’ve moved locations or if loggers are illegally encroaching on their lands.

But in Amazonian countries with fewer resources to police the region, like Peru – home to some 15 identified uncontacted tribes – conservationists struggle to protect the region and its isolated inhabitants from loggers and prospectors. Unfortunately, their isolation means they’re susceptible to diseases from the outside world. It’s part of the reason why anthropologists and indigenous-rights advocates support their continued isolation.

But these tribes are part of our shared humanity, and their unique cultures are worth preserving and protecting, too.

Read more:

• How much the best paid workers in 20 professions earn

• Seven outdated men’s style ‘rules’ that you can now ignore

• 16 skills that are hard to learn but will pay off forever

Read the original article on Business Insider UK. © 2016. Follow Business Insider UK on Twitter.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments