With affection and humour, Patricia Piccinini probes the boundaries of human and other

Her sculptures are breathtakingly lifelike, however, we can’t be sure what life they are like

Patricia Piccinini’s sculptures are deeply disquieting. Walking through Curious Affection, her new solo exhibition at Brisbane’s Gallery of Modern Art, is akin to entering a science laboratory full of DNA experiments. Made from silicone, fibreglass and even human hair, her sculptures are breathtakingly lifelike, however, we can’t be sure what life they are like. The artist creates an exuberant parallel universe where transgenic experiments flourish and human evolution has given way to genetic engineering and DNA splicing.

Curious Affection is a timely and welcome recognition of Piccinini’s enormous contribution to reaching back to the mid-1990s. Working across a variety of mediums including photography, video and drawing, she is perhaps best known for her hyperreal creations.

As a genre, hyperrealism depends on the skill of the artist to create the illusion of reality. To be truly successful, it must convince the spectator of its realness. Piccinini acknowledges this demand, but with a delightful twist. The excruciating attention to detail deliberately solicits our desire to look, only to generate unease, as her sculptures are imbued with a fascinating otherness. Part human, part animal, the works are uncannily familiar, but also alarmingly “other”.

With more than 70 works on display, the entire ground floor has been handed over to Piccinini, a first for an Australian artist. The flamboyant exuberance of GOMA’s soaring atrium is utilised and the visitor is welcomed by an enormous inflatable sculpture, Pneutopia (2018).

With echoes of Piccinini’s Sky Whale (2013), commissioned by the ACT Government as part of its centenary celebrations, Pneutopia moves with air currents circulating in the atrium, as if it were softly inhaling and exhaling. This is Piccinini fully unleashed, at her theatrical best.

The artist has created a parallel universe for us to engage with her most recent installations commissioned especially for the exhibition. The sheer power of endless repetition comes to the fore, as the spectator is engulfed by 3,000 biomorphic flowers, standing tall on metre-long stems. The ivory white of the flowers glows eerily against the dark gallery space.

Titled The Field (2018), these uterine-shaped ceramic forms, complete with ovaries and fallopian tubes, reach back in history, evoking ancient fertility figures such as the Venus of Willendorf. Sensitive to movement, the flowers sway tenderly, quietly acknowledging the viewer’s physical presence.

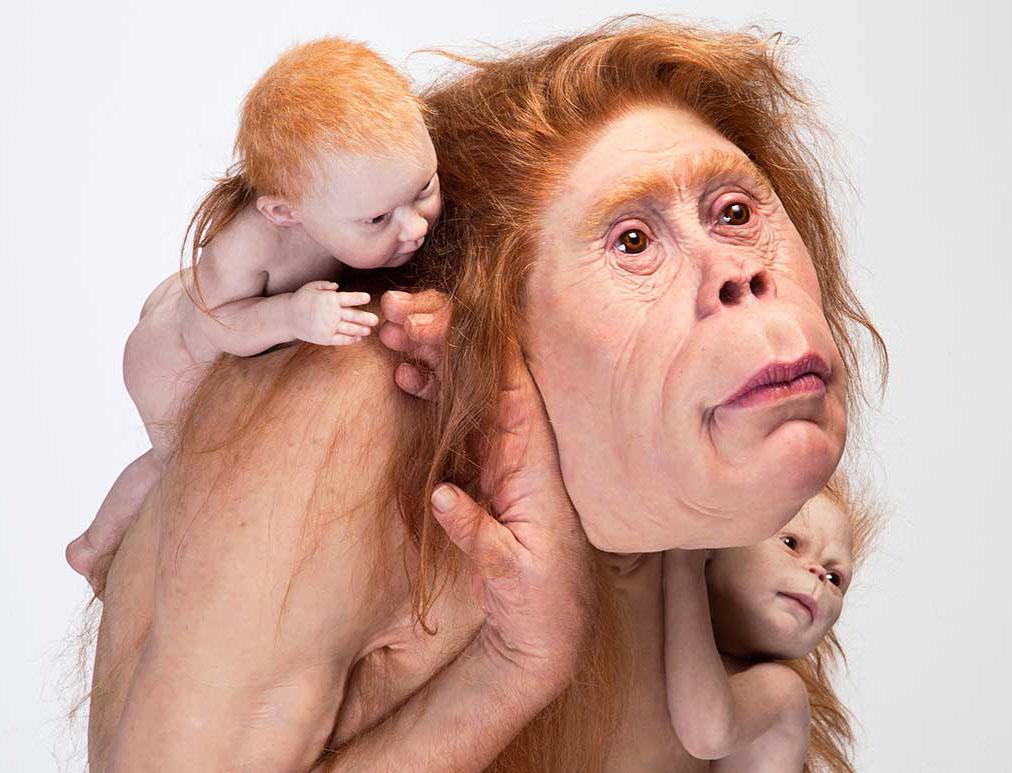

A pathway has been forged through the field as the visitor meanders through this teeming world brimming with abundant fecundity. The architectural flexibility of GOMA’s gallery spaces is exploited, as Piccinini creates viewing platforms as vistas from which to survey the work from above. The theme of fertility and reproduction is continued in Kindred (2018).

An orangutan-like mother gently holds her two babies. Forms are fluid here, as Piccinini probes the boundaries demarking artificial from natural, human from the posthuman. She leaves us with no easy answers, suggesting the borders are unstable, mutable and in flux.

The experience of looking down and through is accentuated with The Grotto (2018) where scores of suspended forms line the walls of a cave-like space. Neither bats nor fungi, but perhaps somewhere in between, the installation reminds us of Piccinini’s enduring concerns: the shared interconnection between species. The installations are replete with their own unique soundscapes, creating an additional layer to this immersive, self-contained world.

In one corner rests a vintage caravan. On closer inspection, the viewer is recast as voyeur. Peering through the caravan’s window, we are met with two human-like forms interjoined in an intimate embrace.

This relationship is rendered compassionately and tenderly by the artist. Piccinini is staging a confrontation that is not always easy or benign for the spectator and it is this disquiet that she is asking us to confront and examine.

Keen Piccinini followers will not be disappointed in the exhibition’s scope. Pivotal works from throughout her career including The Young Family (2002) are on display. Part pig, part human, the mother suckles her offspring. Her excess flesh sags and wrinkles and we are left to uneasily contemplate her babies’ future.

Inspired by advances in genetically modified pigs to generate replacement organs for humans, we are reminded that Piccinini has always been at the forefront of debates concerning the possibilities of science, technology and DNA cloning. She does so, however, with a warm affection and sense of humour, eschewing the hysterical anxiety frequently accompanying these scientific developments.

Beyond the astonishing level of detail achieved by working with silicon and fibreglass, there is an ethics at work here. Piccinini is asking us not to avert our gaze from the other, and in doing so, to develop empathy and understanding through the encounter.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks