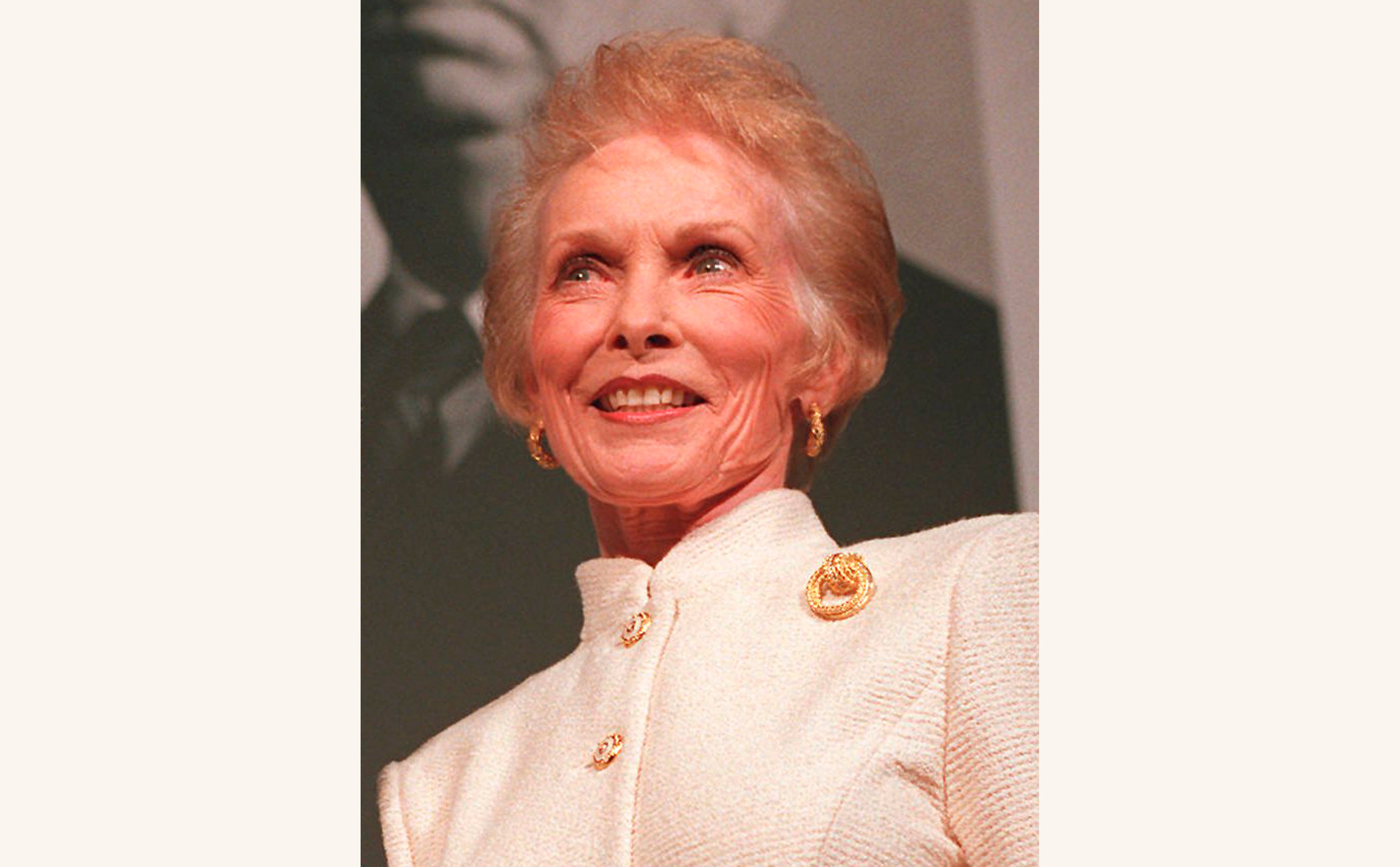

Pat Hitchcock, daughter of Alfred Hitchcock, dead at 93

The only child of Alfred Hitchcock has died

Patricia Hitchcock O’Connell, the only child of Alfred Hitchcock and an actor herself who made a memorable appearance in her father’s “Strangers on a Train” and championed his work in the decades following his death, has died at age 93.

Hitchcock died Monday in her sleep at home in Thousand Oaks California her daughter Tere Carrubba said Wednesday. She died of natural causes, said Carrubba.

“She was always really good at protecting the legacy of my grandparents and making sure they were always remembered,” said Carrubba, one of Patricia Hitchcock's three daughters. “It's sort of an end of an era now that they're all gone.”

Known to many as Pat Hitchcock, she was born in London to Alfred Hitchcock and Alma Reville Hitchcock in 1928 and spent much of her life in and around the family business. During her childhood, Alfred Hitchcock directed such classics as “The 39 Steps,” “The Lady Vanishes” and “Shadow of a Doubt,” moved to California after signing a multipicture deal with producer David O. Selznick and rose to global fame as the “Master of Suspense.” Alma was his indispensable adviser, a former film editor through whom he vetted story ideas and screenplay treatments.

“My mother had much more to do with the films than she has ever been given credit for — he depended on her for everything, absolutely everything,” Pat Hitchcock told The Guardian in 1999.

Pat would visit her father’s movie sets and by her teens was acting in school plays and appearing on stage, including the Broadway productions “Solitaire” and “Violet.” She was admitted to London’s Royal Academy of Dramatic Art in 1947 and was about to graduate when her father contacted her and said he had a role for her in his new film, “Strangers on a Train,” adapted from the Patricia Highsmith novel. The 1951 production starred Robert Walker and Farley Granger as strangers who meet on a train and agree — at least Walker thinks they agree — to a double murder: Walker will kill Granger’s wife, and Granger will kill Walker’s father. Pat Hitchcock plays the sister of a woman (Ruth Roman), with whom Granger is in love.

Walker duly carries out his side, strangling Granger’s wife on the grounds of an amusement park, and pressures Granger to honor the bargain. He turns up at a party attended by Granger and chats up an elderly woman about the best way to kill someone — strangulation. He has placed his hands on her neck, when he looks up and sees Pat Hitchcock staring back in horror. Unnerved by her resemblance to his murder victim — they wear similar glasses — he nearly chokes the guest to death. Hitchcock’s character later sobs that she felt as if she was the one he might have killed, leading to suspicions about the murder of Granger’s wife.

“I think he was using her as the audience,” Pat Hitchcock, interviewed for a 1997 BBC special on her father, said of her character. “I think he was having her go through what the audience went through.”

Hitchcock was a lively, witty actor with a heart-shaped face and her other acting credits included the TV sitcoms “My Little Margie” and “The Life of Riley” and several roles in the TV series “Alfred Hitchcock Presents.” She also had parts in her father’s “Stage Fright” and in his horror masterpiece “Psycho,” in which she plays an office colleague of Janet Leigh, who later in the film is famously stabbed to death in a motel shower.

More recently, she worked for Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine, appeared at numerous film festivals and in numerous Hitchcock documentaries and contributed photographs and a foreword to “Footsteps in the Fog: Alfred Hitchcock’s San Francisco,” by Jeff Kraft and Aaron Leventhal. She also co-authored a book on her mother, who died in 1982, “Alma Hitchcock: The Woman Behind the Man.” (Alfred Hitchcock died in 1980).

Pat Hitchcock was married for more than 40 years to Joseph O’Connell, who died in 1994. They had three children.

She would insist that her childhood was happy and that her parents were normal, but she wasn’t spared her father’s distant, controlling nature and his skewed and sometimes cruel sense of humor. As a girl, she often ate alone, was sent to boarding school and deprived of a college education when her father decided she should instead return to England. She would express regret that he didn’t cast her in more of his films.

“I certainly wish he’d believed in nepotism,” she liked to say.

At home, the director once painted a clown face on her while she was sleeping, anticipating her shock when she awoke the next morning and first looked in a mirror. During the filming of “Strangers on a Train,” knowing her fear of heights, he bet her $100 that she wouldn’t ride a Ferris wheel on the set. She disputed a story from Andrew Spoto’s 1983 biography “The Dark Side of Genius” that he left her stranded, and terrified, for an hour.

“What happened is they turned off the lights and pretended they were going away — for all of what I’d say were 35 seconds — and put the lights on and we came down,” she told the Chicago Tribune in 1993. “The only ‘sadistic’ part is that I never got the hundred dollars.”

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks