John Richardson's final Picasso book arrives in November

Few books have been more anticipated among art lovers

In the fall of 2018, art historian John Richardson fell critically ill and died the following March, at age 95. He left behind a distinguished record as a critic, curator and biographer and questions about the fate of one of the art world's longest awaited volumes, his fourth and final book on Pablo Picasso

Shelley Wanger, his editor at Alfred A. Knopf, explained during a recent interview that she and Richardson had been working “on a typed manuscript” that they would review together when she came to see him each week. By the time he was hospitalized, they had what she calls “essentially a finished manuscript,” save for end notes, illustrations and some additional research.

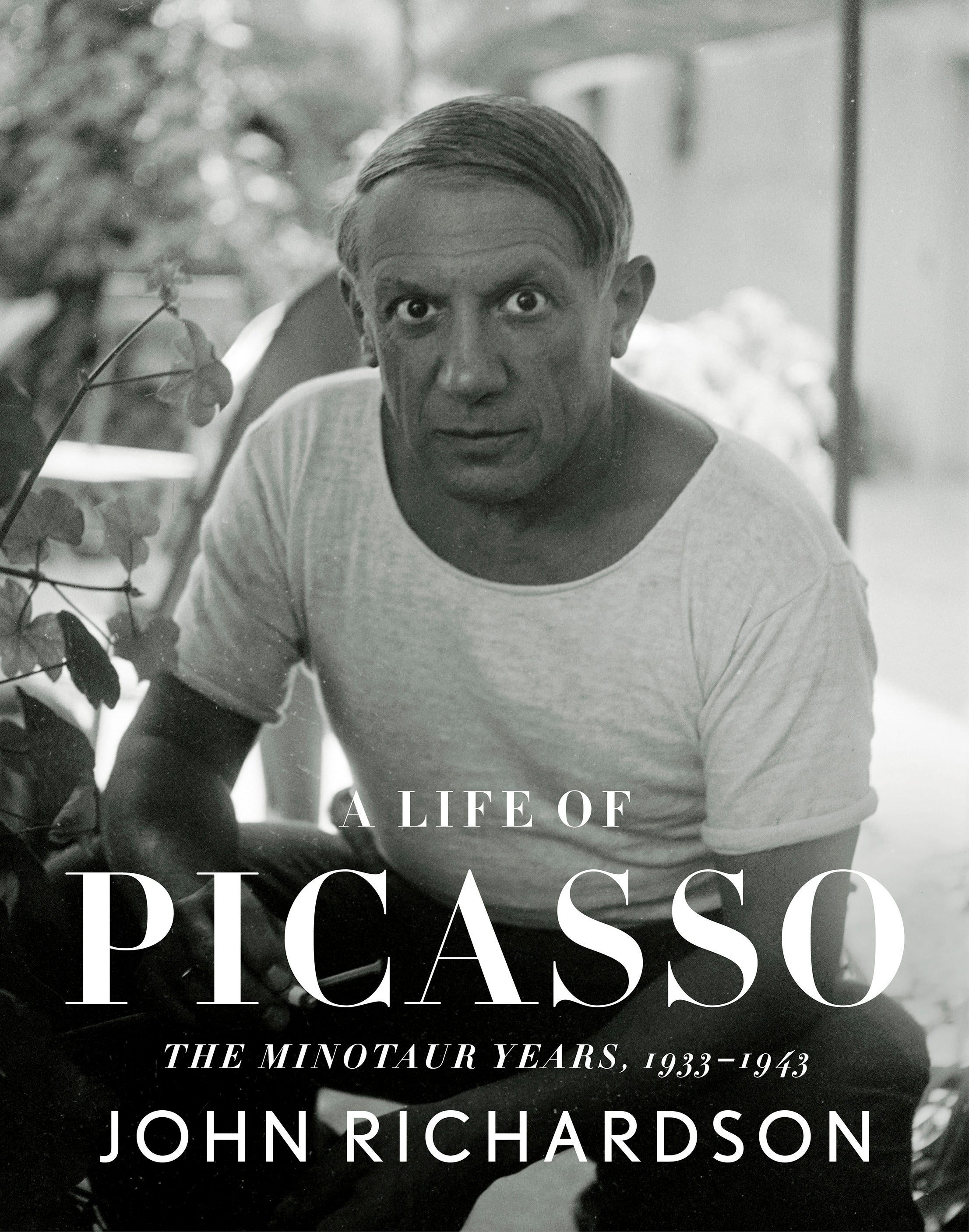

Richardson's “A Life of Picasso: The Minotaur Years,” which comes out Nov. 16, completes a project he began more than 30 years ago with “The Prodigy” and continued with “The Cubist Rebel” and “The Triumphant Years.”

Like Robert Caro's Lyndon Johnson series, Richardson's books have been a story of testing and rewarding the patience of readers and critics. Each volume took years to complete — “The Triumphant Years” came out in 2007. Each was praised in every way a biographer could ask for — for his prose and for his knowledge, for his singular appreciation of Picasso's achievements and, despite a personal friendship with Picasso and family members, for his willingness to document the artist's most troubling flaws.

“I think his are the most important of the Picasso biographies," says Picasso's grandson, Bernard Ruiz-Picasso, co-president of the art foundation FABA, which includes some of his grandfather's works. He noted that Richardson benefited from knowing not just the artist but Jean Cocteau and other friends and peers.

“He had a much larger, wider picture (than other biographers) of what everyone was doing. It wasn't only facts, because facts can be kind of boring. What you have is accuracy and insight."

“The Minotaur Years” covers 1933-43, when the Spanish artist was in his 50s and confronting the spread of fascism and Nazi Germany in Europe. He was ever impatient and in transition, exploring new styles and art forms, whether surrealistic poetry, the mythological drawings that give the book its title, or the epic anti-war painting “Guernica ” his famous response to the 1937 Italian and German bombing of the Basque town during the Spanish Civil War.

Picasso was also, as ever, in transition in his private life. He was estranged from his wife, the Russian dancer Olga Khokhlova, and spending much of his time with other women, notably the poet-photographer Dora Maar, who met the artist in 1935 and became his lover and inspiration for numerous paintings.

Wanger says the book will be “the most comprehensive treatment of Picasso’s life and work in the 1930s and early 40s." It will include previously unpublished correspondence with, among others, his wife and with the poet (and Picasso lover) Alice Rahon. Richardson also drew upon his conversations with Maar and with the son of Pablo and Olga Picasso, Paolo Picasso.

The narrative will reflect an “an insider point of view” that “very few if any other writers on Picasso had,” according to Wanger.

One of the researchers for “The Minotaur Years,” Ross Finocchio, said Richardson was “satisfied with the ending of the book." But it does reflect Richardson's declining physical powers. The fourth volume is around 300 pages, by far the shortest of his Picasso biographies, and his failing eyesight made writing and reviewing documents an increasingly slow process.

Delays in “The Minotaur Years" were also caused by Richardson's otherwise ageless energy. Starting in 2008, as a consultant to the Gagosian gallery, he helped present six Picasso exhibitions praised by The New York Times' Roberta Smith as among the best art shows of the 21st century. Richardson was able not only to present rarely seen Picasso works, but to gather art from museums and private collectors worldwide.

“John was so much fun,” says Gagosian curator Michael Cary, who worked with Richardson on the Picasso shows. “And while he took everything he did very seriously, he was funny and playful and a storyteller. Everything had a story. He could look at one of Picasso's works and he could narrate and narrate and narrate.”

For those assisting him on his book, work was an event in its own right. Researchers Finocchio and Delphine Huisinga speak with fresh amazement about his 5,400-square-foot Manhattan loft, filled with art by Picasso, Warhol and Lucien Freud among others. Huisinga remembers the nonagenarian author practically running to them in anticipation of what they learned through their latest research.

"He would ask me, ‘What goodies do you have for me today?’" she says.

Richardson drew upon materials from Paris, Barcelona, London, New York and elsewhere, but his mind was his greatest resource: He seemed to have tracked Picasso's life more closely than even the artist could have managed. Huisinga remembers debating the origins of a circus painting Picasso completed in February 1933. Richardson speculated that Picasso had attended the circus to help celebrate the 12th birthday of Paolo, whom Richardson recalled was born on Feb. 4.

“It sounded like a great idea, but I didn't have anything factual to base it on,” Huisinga says. “But a few weeks after that, I went to the Musee Picasso (in Paris) and found a stub for the circus with that exact date. He had a hunch, and it was verified. He had that date in the back of his mind. Who else but John Richardson would have something like that in the back of his mind?”

Richardson apparently intended all along to end his work in 1943, 30 years before Picasso's death and before he befriended the artist in the 1950s, when both were living in France. But Finocchio and Huisinga remember occasional conversations about a fifth book. At times, he would speak wistfully, as if aware that he would never live to finish it. Other times, he would sound more excited.

“I think we felt that as long as he was working, he was going to stay alive, that it was such a strong motivation to keep going,” Huisinga says, adding that she worried about a “post-partum depression" once the fourth book was done.

“I was almost encouraging him to think about volume five,” she said. “I don't think he expected to write another book, but he would joke once in a while that he had made a pact with the devil that he wouldn't die before he was 100.”

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks