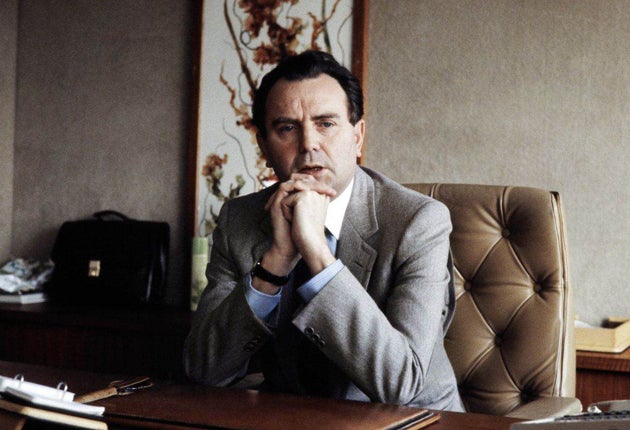

Yves Rocher: Doyen of the French beauty products industry

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Over the last five decades, the French entrepreneur Yves Rocher built the company that bears his name into one of the most recognisable and lucrative brands of cosmetics and beauty products in the world, with an 8,000-strong workforce in France alone, more than 30 million customers and an annual turnover of 2 billion euros.

He made great play of his use of plants and natural ingredients and his humble Breton working-class origins, and based much of his company's activities in and around La Gacilly, the small town in the Morbihan area of Britanny where he was born in 1930, and where he was the elected mayor for 46 years.

"It was in La Gacilly, in the heart of Brittany, that my passion for the plant world was born," he said. "The flowering uplands, the meadows and the forest of Brocéliande, with its myths and legends, fired up my imagination."

He started in business at the end of the Second World War, helping his mother run a haberdasher's after his hat-maker father died when Yves was 14. Selling inhalers and herbal remedies at the local markets, Rocher developed a keen sense of what people wanted. In 1955, a local healer gave him a recipe to make an ointment with Lesser Celandine or Pilewort, a perennial plant used to treat haemorrhoids. Given the "delicate" nature of the ailment and treatment, Roche felt it would be easier to sell the cream he made in the attic of the family home through small ads in the weekly magazines Ici Paris and France Dimanche.

His hunch was correct. The company he launched in 1959 followed the same principles, using plants and flowers, and building a dedicated customer base originally through mail-order catalogues. In 1965 he wrote The Green Book of Beauty, which has been translated into 22 languages. Four years later, he opened his first boutique, on the Boulevard Haussmann in Paris, after a postal strike in 1968 nearly put him out of business. There are now over 500 Yves Rocher shops or beauty salons in France, and a thousand franchises around the world as far afield as Canada, China and Russia. Rocher maintained that his aim was "to treat every woman customer like a queen".

Early on, the claims he made occasionally fell foul of the French equivalent of the Trades Description Act and he had to pay the odd fine. However, his success was based on simple and sound principles. He controlled every aspect of the process: growing flowers and plants in fields that were organic before it became fashionable, because that was how things were done in Britanny, and delivering a good product at a decent price, with presents and samples for repeat customers.

Basing the HQ and most of the company's factories and offices in and around La Gacilly also enabled him to tackle the rural exodus which affected Britanny and much of rural France in the 1960s and '70s. His commitment to the town encompassed a botanic garden which didn't charge admission to the 200,000 annual visitors. In 1998, in partnership with the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle, he opened the Végétarium, a museum dedicated to plants, while this year the Eco-Hotel Spa Yves Rocher in La Gacilly welcomed its first guests.

He played an active role in local politics, as mayor of his home town from 1962-2008 and serving on the regional council in the '80s and '90s. This didn't go down well with observers who felt that as the area's main employer he was an electoral certainty.

The Yves Rocher group also includes the Daniel Jouvance – started by his son David in 1980 – Isabel Derroisné and Docteur Pierre Ricaud cosmetic brands; Stanhome, the US home and family-care products company it acquired in 1997; and the Petit Bateau children's clothing company it bought on the verge of bankruptcy in 1988 and whose fortunes it revived. In 1991, he started the Yves Rocher Foundation, which campaigns "for a greener world" and is run by his son Jacques. The following year, after appointing Didier, another son, head of the company, he announced his retirement. However, after Didier's mysterious death at a shooting range in 1994 he came out of retirement.

Decisive as ever, he skipped a generation and made Bris, Didier's son, his putative heir, and packed him off to the US to study business management. Bris became vice-president in 2007 and was confirmed as company president after his grandfather's passing.

Known to his employees as "Le Patron", Yves Rocher was made Commandeur de la Légion D'Honneur in 2007. He was proud of the fact that the family still owed 75 per cent of the Yves Rocher company and that it was behind only L'Oréal as France's leading cosmetics business.

Yves Rocher, entrepreneur: born La Gacilly, Morbihan, France 7 April 1930; married (three sons, and one son deceased); died Paris 26 December 2009.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments