Wim Kok remembered: Former prime minister of The Netherlands whose social reforms inspired Blair and Clinton

Part of the centrist firmament which dominated European politics in the Nineties, he was forced to step down months before his retirement in 2002

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Wim Kok, prime minister of the Netherlands from 1994 to 2002, who has died aged 80, was a great social reformer who missed his chance to be remembered in the same breath as historical figures such as Oskar Schindler, and Asa Jennings, who saved 250,000 refugees during the Armenian holocaust.

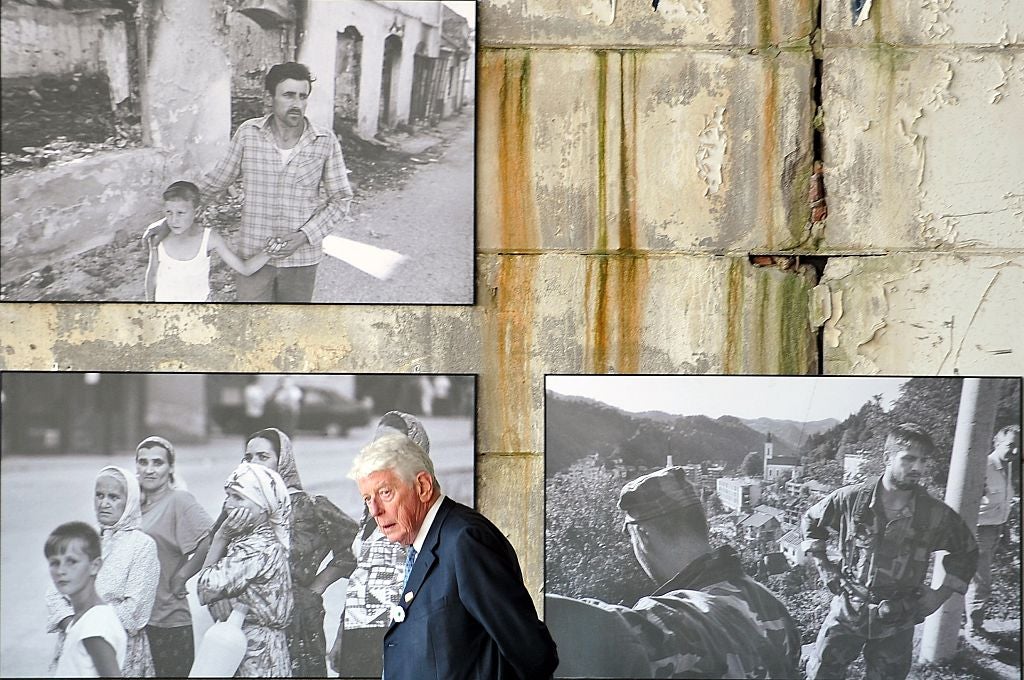

It was under the watch of the former trade unionist, who led the country’s Labour Party for 16 years, that 8,000 mostly Muslim men were massacred in what was supposed to be the UN “safe area” of Srebrenica, in northeastern Bosnia, in July 1995.

That designation was put in place in 1993 to protect Muslims from Bosnian Serb forces.

The Netherlands, both for humanitarian reasons and to improve its visibility on the international stage, sought to have troops on the ground as ethnic conflict grew with the disintegration of Yugoslavia in 1992.

But “safe area” meant little to the Bosnian-Serb General Ratko Mladic.

Unfazed by “Dutchbat”, the nickname of the battalion of lightly armed Dutch troops acting as part of the UN Protection Force, Mladic’s well-equipped army of Republika Srpska, flanked by the Scorpion paramilitary unit from Serbia, encircled the town and proceeded to overrun Dutch observation posts with alarming ease, taking hostages in the process. Thousands of Muslim men and boys were rounded up in trucks and taken to a camp where they were executed.

Far from being at odds with Mladic, who was convicted of genocide and war crimes only last year, the Netherlands stood accused of cowardice and even complicity by some observers, its presence characterised by Dutchbat commander Thom Karremans pictured raising toasts to peace with Mladic, both men in their combat fatigues.

In spite of the international outcry over what the then UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan called the worst mass murder on European soil since the Second World War, Kok remained popular for his centrist policies, which were admired by Tony Blair and Bill Clinton.

The economy had been steered out of the doldrums and unemployment reduced – this was due in part to his adoption of the Dutch “polder model” of economic change by consensus.

“He is someone you would buy a second-hand car from,” the late Elske Ter Veld, a former Dutch state secretary told The Independent in 1997. “Not only that, he is someone who you know would repair the second-hand car before he sold it to you.”

So in 1998, the groundbreaking “purple coalition” of left, right and centre parties led by Labour, was re-elected.

Keen to see the launch of the single currency in 1999, Kok, a European integrationist through and through, had secured a mandate to continue “third way” reforms of the Netherlands’ “tiger economy”, trade unions and the country’s social welfare traditions.

His cabinet’s legacy includes legalisation of same-sex marriage, sex work and euthanasia.

It was not until 2002 – when a report a report by the Netherlands Institute of War Documentation presented its findings after six years and 900 interviews – that Kok, who denied negligence by commanders on the ground, or by his government, over the Srebrenica massacre, was forced to stand down. His cabinet submitted their resignations to Queen Beatrix en masse.

The 7,000-page document said: “Humanitarian motivation and political ambitions drove the Netherlands to undertake an ill-conceived and virtually impossible peace mission.”

While criticising the UN, it added the Dutch cabinet had “adopted an anti-intelligence attitude”.

But Kok did not apologise to the nation which by then was riven by collective guilt.

Kok subsequently worked as a lobbyist for the EU and stood as non-executive director of a number of companies and charitable boards.

Willem (Wim) Kok was born in Bergambacht, a village near Rotterdam, to Willem, a carpenter, and Neeltje de Jager.

He graduated from the elite Nyenrode business school in Utrecht, where he was marked as a leader, before joining the National Association of Trade Unions in 1961. By 1973 he was its chairman, a post he kept until 1982, when the body merged with the Federation of Catholic Unions.

By the time Labour leader and former premier Joop den Uyl retired in 1986, Kok had left his life as a union left-winger to enter the house of representatives (the lower house to the Netherlands’ senate). He was then chosen to lead both the party and the opposition to the right-wing government of Ruud Lubbers.

After the 1989 general election, Kok – who is survived by his wife, Rita, a daughter and two sons – entered a coalition with Lubbers’ Christian Democratic Appeal, serving as deputy prime minister and minister of finance. In 1994, he formed the first governing coalition since 1908 to exclude the Christian Democrats.

Willem (Wim) Kok, Dutch politician, born 29 September 1938, died 20 October 2018

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments