Will Elder: Comic-book artist who drew for 'Mad' magazine and co-created 'Little Annie Fanny' for 'Playboy'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The American satirist and comic-book artist Will (at times Bill) Elder was one of the last surviving denizens of the Crypt of Terror – sometimes the Vault of Horror, on occasion the Haunt of Fear – in other words the downtown New York editorial offices of EC Comics, unequivocally the finest and most influential (as well as the most notorious) producer of comic books in the 20th century.

Elder's natural bent was towards humour, but like all EC artists he could turn his pencil to other genres, and drew tales of horror (for the Haunt of Fear, Tales from the Crypt, etc.), adventure yarns, brilliant war stories (Two-Fisted Tales, Frontline Combat), as well as science fiction and fantasy, before EC launched Mad magazine and he discovered the perfect niche for his zany and subversive talents.

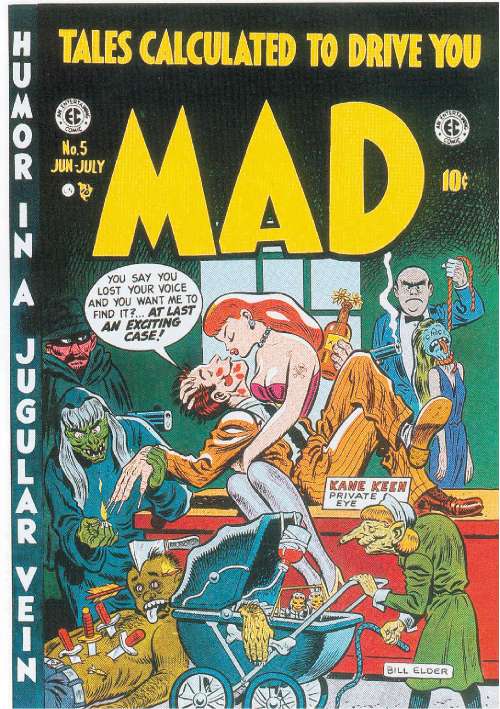

Mad magazine – or Tales Calculated to Drive You Mad: humor in a jugular vein to give it its full monicker – started life in 1952 as a 10-cent comic book spoofing other comic books and comic-book characters ("Mickey Rodent", "Starchie", "Manduck the Magician", "Plastic Sam", et al). So successful was it that three years later EC transformed it into a 25-cent satirical monthly, whose editor, the extraordinarily gifted Harvey Kurtzman, led it off into a whole new comedic direction before falling out spectacularly with the management and marching off (with Elder in tow) to create satirical magazines for other publishers.

Trump, a slick monthly financed by Playboy's Hugh Hefner, failed after two issues; Humbug suffered a similar fate. Help!, on which a young John Cleese toiled for a while (on occasion as a chinless hero in its photo-strip stories), fared rather better, running from 1961 until 1966.

In times of famine Elder went back to drawing war stories, mainly for Atlas Publishing (later Marvel Comics) under Stan Lee. He also flirted with advertising at a time, the 1950s and 1960s, when a good deal of product presentation was still art- rather than photo-based.

While at Help! the Kurtzman-Elder combine created "Goodman Beaver", a good-natured lampoon of other media characters and types, like Superman, Tarzan, and so on. Beaver was a classic idealist-boob schnook, a Candide-like figure to whom disasters occur.

One of the sacred cows the pair parodied was Archie Comics, a firm whose comic books were ultra-family and ultra-pure. Kurtzman and Elder had recognisable Archie Comics characters attending a Roman-style orgy in what looks suspiciously like the Chicago Playboy mansion, having signed a pact with the Devil (who bore a remarkable resemblance to Hugh Hefner). This would have been acceptable if the strip had been left in Help!, but Kurtzman and Elder included it in a paperback collection, Executive's Comic Book (1962). Hefner guffawed; Archie Comics sued. And won.

Out of this débâcle Elder and Kurtzman dreamed up the perfect meal ticket: "Little Annie Fanny" – a comic strip featuring a beautiful blonde innocent-at-large: a grown-up version of Harold Gray's "Little Orphan Annie" but with staggeringly colossal breasts whose clothes fell off at the slightest puff of wind, and whose lot it was to suffer the most outrageous and hilarious sexual indignities and misadventures in each episode's final panels. A delighted Hugh Hefner bought the strip for Playboy, where it ran pretty well monthly for over 25 years.

Elder was born Wolf William Eisenberg in the Bronx, New York in 1921. He attended the New York High School of Music and Art; fellow alumni included Kurtzman, John Severin and Al Jaffee (later a cartoonist on Mad). He studied at the National Academy of Design in Manhattan before being drafted into the US Army, serving with the 668th Topographical Engineers. One of his tasks was drawing maps for the 1944 D-Day landings in Normandy.

After the war he changed his name to Elder, and set up (with Kurtzman and another artist, Charles Stern) as a freelance art studio supplying comic-strips to various publishers.

"It became a hangout for the lost and unemployed," he recalled years later. The short-story writer and cartoonist Jules Feiffer (who had worked in the great Will Eisner's studio) used to drop by, as did (astonishingly) René Goscinny, much later, and on a different continent, the Asterix writer.

Kurtzman landed an assignment with EC Comics, then (1949) beginning to breathe new life into what was already a jaded medium. Bill Gaines (editorial director) and Al Feldstein (chief editor) both had busy imaginations but were certainly not above swiping plots from writers they admired, from de Maupassant to Ray Bradbury. Their horror stories were horrid, yet often witty; their science fiction and fantasy sophisticated and parabolic; their tales of suspense often jaw-droppingly shocking yet at the same time thought-provoking; their artists' roster contained some of the most formidable young talent in American illustration.

Kurtzman took on the war comics and deliberately went against the jingoistic tide – bang in the middle of the Korean war – by often presenting both sides of a conflict (whether in Korea; Berlin or Flanders fields) with a kind of realism and integrity not often seen in the medium.

Elder thrived in this atmosphere, creating a double-act, as inker, with his old schoolfriend John Severin (a superb and speedy penciller) in the combat comic books, while both pencilling and inking his own material for Mad and its offshoot Panic! An extraordinary joke issue was Mad for April 1955, the entire issue given over to the "Bill Elder Story", from birth to senility, Elder drawing every feature about himself.

He also contrived to execute a cover of sustained comic violence for the fifth issue of Mad (June/July 1953), which got it taken off the newsstands in some cities (a meat-cleaver in a head was one bone of contention).

After EC virtually ceased to trade, retaining Mad magazine as its sole publication, due to the backlash against the EC line of horror comics, the artists went their several ways, many of them, however, returning to the Kurtzman/Elder fold after the launch of "Little Annie Fanny".

Instead of its colour mechanically laid down at the printer – the norm for comic books – "Little Annie Fanny" was created as full-colour painted artwork. Kurtzman and Elder dreamed up each episode's gags while Kurtzman laid down detailed sketches for each panel which Elder would then proceed to paint. As deadlines for Playboy were tight, outside help was nearly always called in, so that most of the old EC crowd at one time or another pitched in and laboured over the sumptuous and superbly painted artwork.

Jack Adrian

Wolf William Eisenberg (Will Elder), satirist and artist: born New York 22 September 1921; married 1948 Jean Strashun (died 2005; one daughter, one son); died Rockleigh, New Jersey 14 May 2008.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments