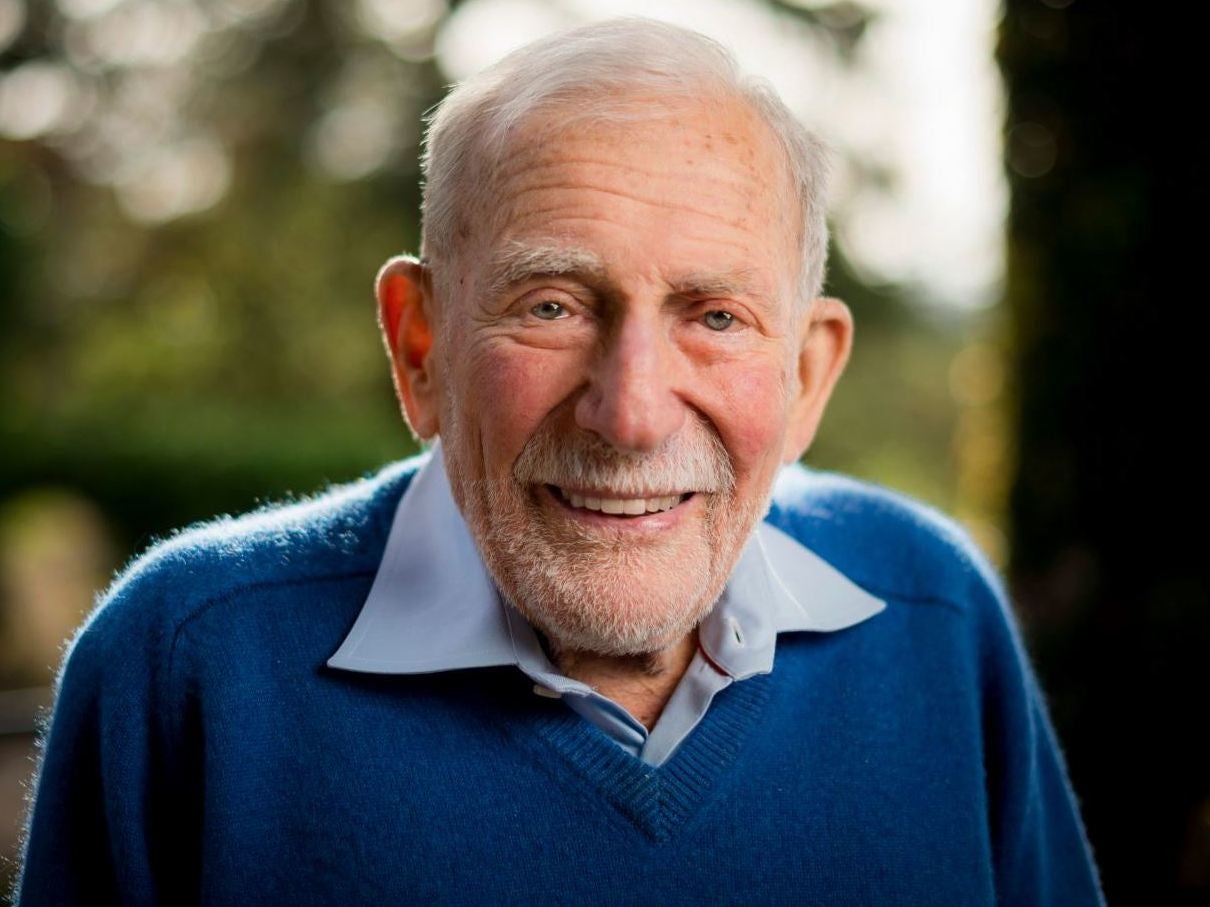

Walter Munk remembered: Oceanographer whose wisdom on waves helped the Allied landings of WWII

His feats with underwater acoustics were key to understanding how different waters are warming, in the race to tackle climate change

Walter Munk was a globally renowned oceanographer who helped ensure the safety and success of Allied beach landings during the Second World War by devising ways to forecast the waves. Decades later he came to fire what became known as the “sound heard around the world” – an underwater emission that reached across oceans – in an attempt to gain a greater understanding of climate change.

The scientist, who has died aged 101, was long associated with the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California in San Diego. Munk was one of the most celebrated oceanographers of his era – a scientist who devoted nearly 80 years to unravelling such questions as where waves begin, why they may break violently or wash ashore gently, how sound travels thousands of miles through water, and what information that journey might reveal about the global ecosystem.

His genius lay in divining the interlocked patterns beneath the seeming clutter and chaos of the world’s oceans, according to Joshua Horwitz, who profiled Munk in his 2015 book War of the Whales. “He was revered in equal measure by surfers and navy admirals for his oracular ability to predict when far-off waves would break on beaches.”

Much like the surfers of popular imagination, Munk found a home on the beaches of California, where he had fled to avoid a life on Wall Street. Born in Vienna to an affluent banking family, he had come to the United States in the early 1930s to attend a boarding school in New York and to carry on the family profession. But he soon discovered he despised banking, bought a convertible and set out for the west coast.

He abandoned finance for science, eventually landing at Scripps, where he apprenticed himself to the director, Harald Sverdrup, a leading oceanographer of his day.

In 1938 Nazi Germany annexed Austria and accelerated a campaign of antisemitic persecution. Dr Munk, whose family had Jewish roots, became a US citizen and served briefly in the army before beginning what would be his seminal research for the navy.

Munk credited Sverdrup with playing a leading role in the development of wave forecasting, which military strategists used in the planning of the amphibious landing on north Africa in 1942, the Normandy invasion in 1944, and throughout the Pacific.

New Scientist magazine credits Munk with saving “countless lives by helping the Allied military determine when troops could make amphibious landings without being swamped by big surf hundreds of metres from a hostile shore”.

Later in his career he attracted wide attention, as well as some controversy, by using ocean acoustics to measure ocean temperatures, and thus to better understand climate change.

In 1991 Munk led an experiment near Heard Island, in the southern Indian Ocean. Understanding that sound travels more quickly in warm water than it does in cold water, Munk sent low-frequency sounds through the ocean. Even the test signal was detected as far away as Bermuda.

“I still can’t believe that happened,” Munk told The San Diego Union-Tribune years later. “We hadn’t even started the main experiment.”

Marine ecologist Enric Sala said Munk “was able to prove at such large scales for the first time that different oceans were warming at different speeds”. Such acoustic tests encountered some opposition from marine biologists who feared they might interfere with migratory patterns of whales and other animals.

For the wide-ranging nature and applications of his work, Munk was dubbed the “Einstein of the oceans” – a comparison Munk rejected. “Einstein was a great man,” he said. “I was never on that level.”

Munk’s father had served for a period as chauffeur to emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria. Years later, in an interview with The New York Times, Munk recalled his father had “the only Rolls-Royce in Vienna”. He often recalled the DeSoto convertible that he drove from New York to his new life in California.

He attended the California Institute of Technology where he received a bachelor’s degree in physics in 1939 and a master’s degree in geophysics in 1940, and the University of California at Los Angeles where he received a doctorate in oceanography in 1947.

After the war Munk provided scientific support for the nuclear testing at Bikini Atoll. “It’s stunning; it’s horrible,” he said years later. “It’s not dark, it’s quite white. You see the boiling and the water vapour above you, like a curtain coming down all around you.”

Throughout the Cold War and beyond he served with the Jasons, who were a group of scientists advising the US military.

Munk won America’s National Medal of Science, bestowed on him by President Reagan in 1983, and a 1999 Kyoto Prize in basic sciences. When Munk accepted the 2010 Crafoord Prize in geosciences from the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences – an award often compared to the Nobel, and which recognised a career that touched on waves and polar ice caps and warming seas – he opened a lecture about climate change by citing from Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s classic poem “Kubla Khan”:

The shadow of the dome of pleasure

Floated midway on the waves;

Where was heard the mingled measure

From the fountain and the caves.

It was a miracle of rare device,

A sunny pleasure-dome with caves of ice!

Munk’s first marriage, to Martha Chapin Munk, ended in divorce, and his second wife, Judith Horton, died in 2006 after more than 50 years of marriage. He is survived by two daughters from his second marriage, as well as his wife Mary Coakley Munk.

Walter Heinrich Munk, oceanographer, born 19 October 1917, died 8 February 2019

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks