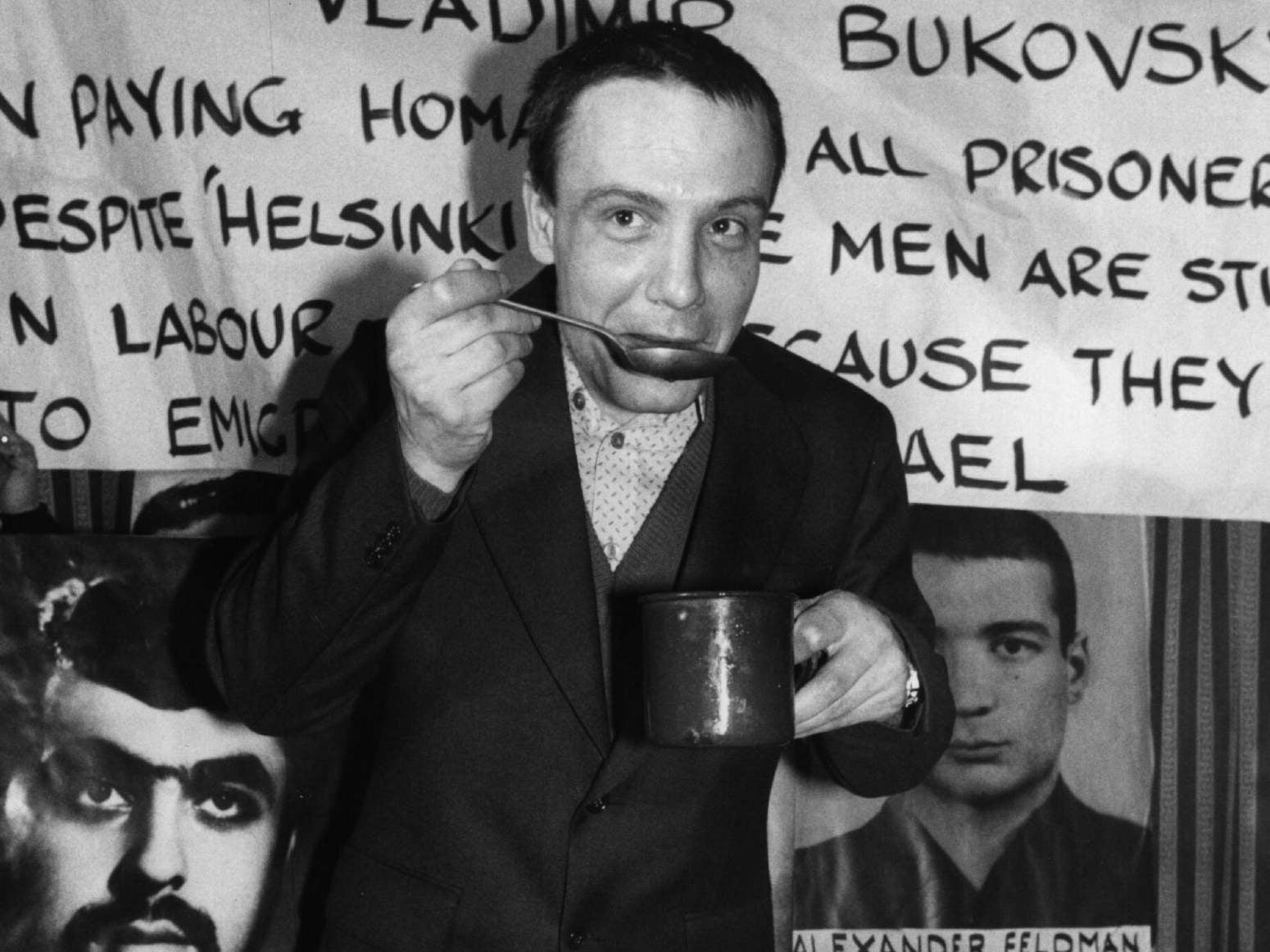

Vladimir Bukovsky: Dissident who exposed Soviet Union abuses

He gained support and admiration in the west for revealing the practice of consigning political prisoners to psychiatric hospitals

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

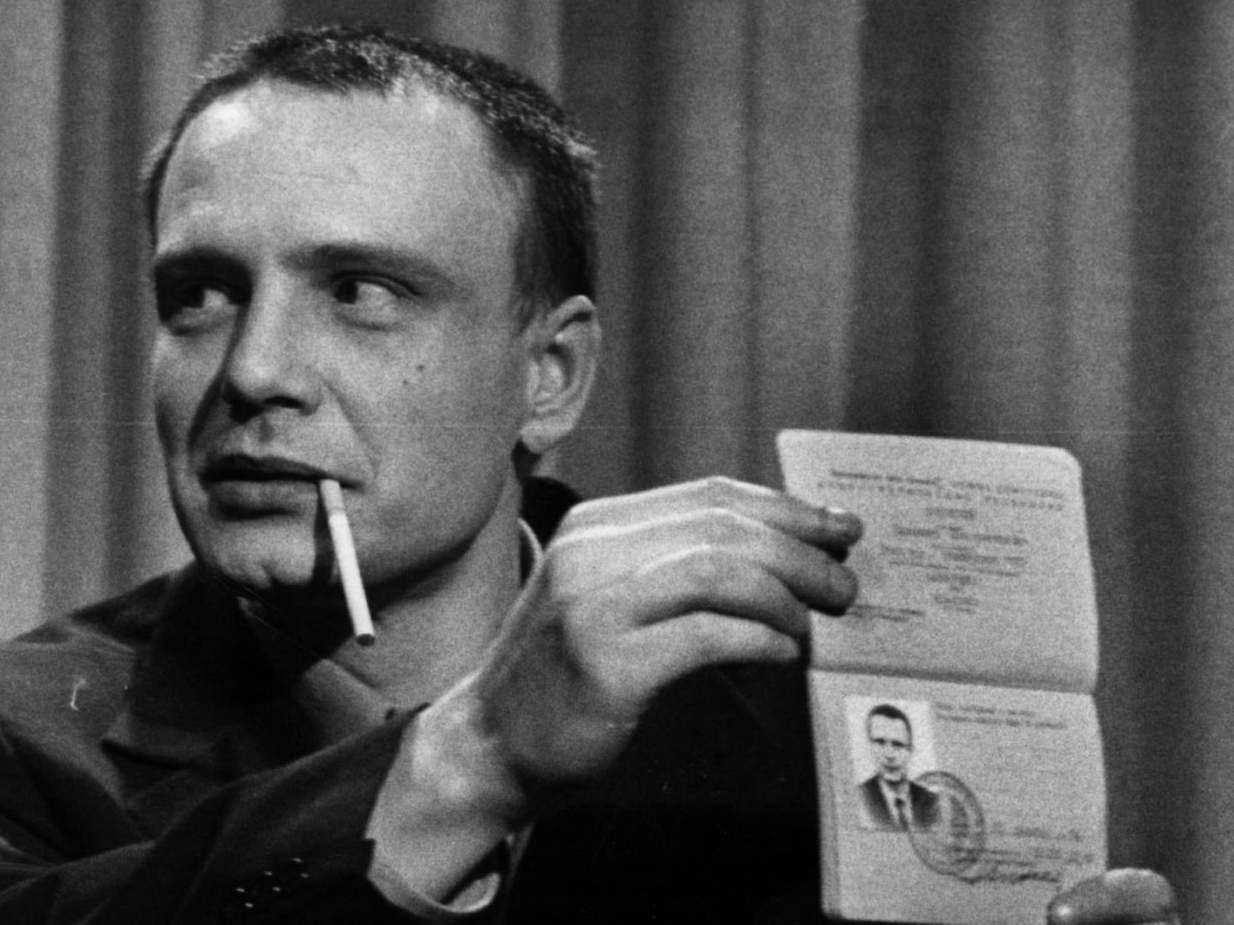

Your support makes all the difference.When Vladimir Bukovsky was released from a Soviet prison in 1976, he was 33 and had already spent about a third of his life in captivity. A dissident since his student days, he had attracted the ire of Soviet authorities – and the admiration of political leaders, human rights advocates, journalists and other supporters in the west – with his unstinting campaign to reveal abuses of communism.

Bukovsky, who has died of a heart attack aged 76, was best known for publicising the Soviet practice of branding dissidents, himself among them, as mentally ill and incarcerating them in psychiatric hospitals that functioned effectively as prisons where detainees lacked even an illusion of legal recourse.

Even after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, while living in exile in Cambridge, he protested the suppression of basic freedoms in his homeland. Russian president Vladimir Putin, he said, was a “vengeful man, unpredictable and petty-minded”.

An inveterate dissident, Bukovsky was expelled from his high school and then, in 1961, from Moscow University for publishing writings critical of the Soviet regime and its trappings. His other early offences included organising public readings of the works of writers such as Boris Pasternak, the Nobel Prize-winning author whose book Doctor Zhivago had been banned in the Soviet Union, and Osip Mandelstam, regarded as one of the greatest Russian poets of the 20th century, who died in the gulag.

Bukovsky was first arrested in 1963, the beginning of nearly 12 years that he would spend in and out of prisons, carrying out forced labour or consigned to the psychiatric hospitals whose existence he later helped to expose. In an effort to stifle protest, Soviet psychiatrists diagnosed dissidents with supposed disorders such as “sluggish schizophrenia” and placed them in asylums. If the detainee did not accept the diagnosis, “it is considered a sign of a more advanced state of his illness, and he is treated accordingly”, Bukovsky wrote in 1977. “If he does not yield, he may remain there forever. I know of cases where people have spent more than 10 years in psychiatric hospitals.”

During his imprisonment, Bukovsky’s captors attempted to thwart his hunger strikes by force-feeding him through the nostril, an excruciating procedure that led him to denounce torture in all forms.

Bukovsky’s plight attracted the attention and condemnation of intellectual figures including Arthur Miller, Edward Albee and Vladimir Nabokov, as well as Amnesty International and members of the US congress. In 1976, in a dramatic episode of the Cold War facilitated by the United States, he was freed in exchange for the release in Chile of Luis Corvalan, the leader of the Communist Party in that country.

Vladimir Konstantinovich Bukovsky was born in 1942, in Belebei, a town in the Urals, where his family had sought safety during the Second World War. They returned to Moscow after the war. His father was a member of the Soviet writers’ union, and his mother wrote children’s programmes for Radio Moscow.

Bukovsky studied biophysics before he was expelled from Moscow University, later resuming his studies at King’s College Cambridge and Stanford University. He wrote books including a memoir, To Build a Castle: My Life as a Dissenter, and the volume Judgment in Moscow: Soviet Crimes and Western Complicity.

During his exile, Bukovsky returned to Russia on occasions, including during the run-up to the 2008 presidential elections, in which he sought to challenge Putin’s successor, Dmitry Medvedev. Bukovsky was disqualified from the election, which Medvedev won before returning the post to Putin in 2012.

In recent years, Bukovsky again made headlines after British prosecutors charged him with 11 counts of child pornography offences. He alleged that the illegal materials had been planted on his computer as a form of kompromat, or compromising material commonly used in the former Soviet Union to embarrass of blackmail political adversaries. After several delays, his trial was indefinitely postponed in 2018 because of his ill health.

He is survived by a sister.

Vladimir Bukovsky, human rights activist, born 30 December 1942, died 27 October 2019

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments