Verily Anderson: Writer of humorous, optimistic children's books and memoirs

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

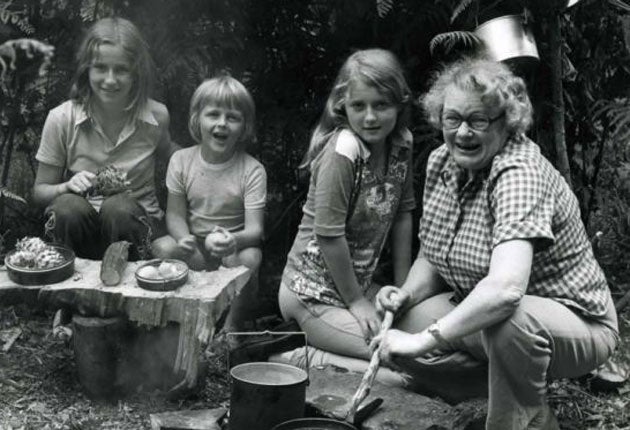

Your support makes all the difference.Verily Anderson was the author of more than 30 books and she died, aged 95, the day after finishing her latest, at her home in Norfolk. Her amusing autobiographies about bringing up five children on a shoestring included Spam Tomorrow, Daughters of Divinity and Beware of Children. "She has one practically unknown gift," wrote the novelist Elizabeth Bowen, "she can write what might seem a sustained tall story and at the same time make it convincing; at times grimly so."

She was born Verily Bruce, the fourth of five children, in 1915, and was named by her rector father Rosslyn Bruce after Jesus's proclamation in the Gospels. She was educated at Normanhurst school in Sussex, where ballroom dancing and fox hunting were on the curriculum; and at the Royal College of Music, where she realised she would never become a concert pianist.

Using her Girl Guide badges as qualifications, she then worked as a designer of toffee-papers, a chauffeur, and a sub-editor on The Guide, the magazine of the Guide Association. A resourceful woman, when she set up a Brownie pack she used old horse reins for the belts and made the uniforms out of brown curtains. Her 10 books about the adventures of a Brownie pack were considered by the Girl Guide Association to be too exciting to endorse.

In 1939, she enlisted as a mechanic with the FANYs but was soon court-martialled for backing her truck into a gate-post. She was found not guilty, but in 1940 deserted to marry Donald Anderson, a speech writer in the Ministry of Information who was 18 years her senior. Their first home was a top-floor flat in Mayfair. "The cheapest place to live in London during the Blitz," she said.

As babies began to arrive and Donald's health failed, Anderson supported the family by reading scripts for Warner Brothers, editing the Girls Friendly Society magazine, and taking in lodgers – who fed her stories for articles and radio talks.

Her first book, Spam Tomorrow, was published by Rupert Hart-Davis in 1956. "This is a genuinely bizarre book," wrote Elizabeth Bowen. "A new kind of wartime experience – new, that is, to literature; the job of marrying and having babies." The copy held by the Imperial War Museum has been used by many writers, including Juliet Gardiner, Virginia Nicholson and Sarah Waters for their research into the Second World War in London.

Her optimistic style, even when detailing domestic disasters and wartime tragedies, cheered up countless hospitalised, bereaved and widowed readers. The Tatler wrote, "Mrs Anderson has what amounts to genius for dovetailing terror into what might seem farce. She also has the power to make one feel that nothing is too good (or bad) to be true. She's unique."

In 1954 the Anderson family moved to Sussex to run a holiday hotel for the children of parents living abroad. "The Freedom of Old Farm Place", with its philosophy of no rules, regular meals or enforced baths, was endorsed by Lord Hailsham, the Astronomer Royal and the Bishop of Gibraltar. The hotel featured on BBC TV's Tonight, and the Evening News newspaper said, "I defy anyone not to be captivated by it all, and not to be extremely thankful that it is Mrs Anderson – and not himself or herself – who runs this infant pandemonium."

When Donald died in 1957, leaving five children aged three to 15, Anderson wrote with increased vigour, and her next book, Beware of Children, was turned into the 1960 film No Kidding by the Carry On producers, starring Leslie Phillips, Geraldine McEwan and Joan Hickson.

Scrambled Egg for Christmas described the family's move to the Bayswater studio of Anderson's aunt Kathleen, the sculptor and widow of Captain R F Scott. Her children flourished: Marian went to art college, Rachel wrote her first novel, Eddie practised ornithology in Hyde Park, and Janie and Alex edited their own newspaper. "Verily shaped us all by allowing us to find our own strengths," said Eddie, now a television director. The family were encouraged to sew, paint and write. Pocket money was earned by writing articles and selling paintings on the Bayswater Road railings.

A descendant of the Barclays, Buxtons and Gurneys of Norfolk, Anderson wrote several books on their exploits as bankers, philanthropists and prison reformers. The Northrepps Grandchildren (1968), about her grandparents' home in Norfolk, is still in print after 42 years. Her favourite ancestor was her great-great-grandfather, slavery abolitionist Sir Thomas Fowell Buxton who said, "With ordinary talents and great perseverance, all things are attainable".

Anderson's talents were extraordinary – she learned to read music at four years old, and then played the violin and rode a bicycle simultaneously. When times were tough, she threw a party serving punch made from tea and sliced oranges, and using aspic and peas she could make one chicken go round everyone. The result was usually more commissions from editors and publishers.

In 1965 her friend Joyce Grenfell bought her a house in Norfolk, where she met her distant cousin Paul Paget, the architect and surveyor of St Paul's Cathedral. They married in 1971 with Grenfell as maid of honour and Sir John Betjeman as best man.

For her 90th birthday, she invited 140 relations, aged from one to 104 years old, to dance the night away to her grandchildren's jazz band. The next morning she went riding, for the first time in 20 years.

Soon after that her sight began to go but, ever optimistic, she undertook the rigorous training needed to host a guide-dog. Alfie, the RNIB dog she obtained as a result, inspired her article in The Author about how Milton might have adapted to having a guide-dog. The day before she died, she finished writing her latest book, a memoir of Herstmonceux Castle in Sussex.

"Verily Anderson goes to her work with zest," wrote Janet Adam-Smith, reviewing The Last of the Eccentrics in 1972, "combining daughterly affection with humorous detachment... and a conviction of the reality of goodness and love."

She leaves her five children as well as numerous grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Verily Anderson (nee Bruce), writer: born Birmingham 12 January 1915; married 1940 Donald Anderson (died 1957; one son, four daughters), 1971 Paul Paget (died 1985); died Northrepps, Norfolk 16 July 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments