Vanya Kewley: Film-maker who alerted the world to the plight of occupied Tibet

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Personal courage and a commitment to exposing human rights abuses were the qualities that made the documentary-maker Vanya Kewley admired and trusted by commissioning editors across British television.

Never was that courage more on display than when she made Tibet: a Case to Answer (1988), the first film from deep inside the region since China's invasion in 1949. Disturbed by claims of genocide, torture, the destruction of monasteries and art treasures, the looting of natural resources and the establishment of a nuclear base, Kewley set out to obtain first-hand accounts. In 1985, she began to establish contacts inside Tibet, and two years later persuaded the commissioning editor David Lloyd to fund Channel 4's most expensive documentary to date, for the current affairs series Dispatches.

Her clandestine six-week trip was meticulously planned; arrangements were made with "fixers" inside Tibet and an exile in India was hired as a translator. Kewley would share Sony Video 8 tourist cameras with the American cinematographer Sean Bobbitt. But, after entering China alone on a three-month tourist visa, Kewley found her plans falling apart. Trains and planes from Guangzhou to Lanchow, her rendezvous-point with her Tibetan co-conspirators, were cancelled for more than a week. Kewley admitted to emotions ranging from fear to terror over the weeks as she worried about her cover being broken.

From Lanchow, she teamed up with Bobbitt in Chengdu; they headed for Tibet by plane as part of a group on a five-day tour of Lhasa, the country's capital. There, she found the indigenous population swamped by Chinese – confirming another claim, that Tibetans were now outnumbered in their own land.

After more delays, Kewley replaced her translator – concerned that he might be a collaborator – and began the filmed interviews that would bring to viewers in 18 countries an insight into the suffering of those in this remote, cut-off region. A former teacher told of the Chinese dividing Tibetans into work units, feeding them starvation diets and beating and torturing many. Until recently, the use of the Tibetan language had been forbidden, and books were burned and monuments destroyed in an attempt to wipe out an entire culture. Four young nuns recalled electric cattle prods being applied all over their naked bodies after they staged a peaceful demonstration calling for Tibetan independence.

When Bobbitt fell ill and left, Kewley filmed alone – and the horrors worsened. A former monk who had been jailed and tortured after confronting Chinese tanks talked of prisoners being shot in "batches" and the survivors resorting to eating human flesh to feed themselves. "Seeing the beads of sweat glisten on his forehead, his eyes glaze with pain as he talked, was one of the most traumatic experiences of my career," wrote Kewley in her 1990 book Tibet: Behind the Ice Curtain.

On a 4,000-mile journey by van into the interior of the region with just her Tibetan fixers, she met farmers and nomads in the countryside, heard more stories of torture, mass graves and cultural destruction, and witnessed undersize children. She also filmed the nuclear base, with interviewees claiming that babies were being born with deformities and animals dying possibly as the result of a radiation leak; a Chinese doctor revealed that he had been made to perform enforced abortions and sterilisations. Throughout, occupation forces were never far away.

Kewley persuaded a French mountaineer to smuggle most of the film footage out before she left on her own flight. Although the documentary was screened for British MPs and US Congress members, Kewley despaired that conditions for Tibetans seemed to worsen and that the world was more interested in trading with China.

The historic trip was the culmination of Kewley's fascination for Tibet, which began as a child in India, where she was born of a French mother and a British diplomat father in Calcutta who shared his deep interest in the region with his daughter. Kewley was educated at convent schools in India, France and Switzerland, and studied philosophy and history at the Sorbonne, in Paris, before moving to London and qualifying as a nurse.

In 1965, she joined Granada Television as a researcher on a regional news programme. Then she became a producer and director on World in Action (1968-71). In 1969, Kewley was captured and beaten by soldiers while making a film about genocide in South Sudan – her first foreign assignment – and took a film crew into the Nigerian Civil War, where a year later, she secured an exclusive interview with the leader of the Biafran forces.

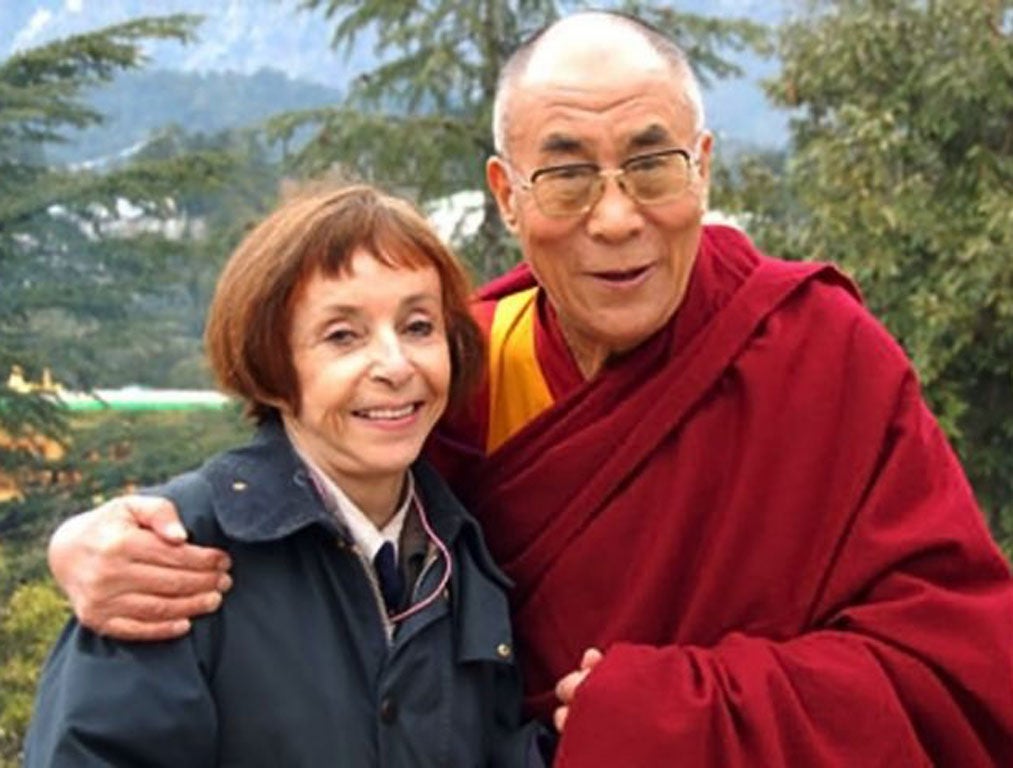

Switching to ITV's This Week in 1972, she made several documentaries and was pinned down behind a foot-high hillock for an hour by Vietcong small-arms fire while filming in Vietnam. Then came a period with the BBC religious and ethics series Anno Domini (1975-77) and Everyman (1977-78). Kewley interviewed Tibet's exiled Dalai Lama at his home in the Himalayas for her 1975 film The Lama King and remained a lifelong friend, making her final visit to him last December. Her 1975 documentary on religious persecution in South Korea won an award at the International Christian Television Week.

In Soldier for Islam (1976, updated 1978), she interviewed Libya's Colonel Gaddafi. Accused of being favourable to him, Kewley retorted: "I don't make him look attractive. He is very attractive, very sexy, very sensuous."

In 1991, she made Voices from Tibet. Entering the region again, she revealed that martial law still existed despite a Chinese claim that it had been ended. In 1993, Kewley was diagnosed with Parkinson's disease and gave up documentaries, returning to her first career as a nurse, offering her services in Rwanda and Bosnia.

In 2000 she married Michael Lambert, a soil scientist who died of bone cancer in 2004. As well as sponsoring the education of two girls and a boy – Pema Choezam and Choezam Tsering, from Tibet, and Jean-Paul Habineza in Rwanda – she also adopted them and they survive her.

Vanya Sarah Kewley, documentary film-maker: born Calcutta, India 8 November 1937; married 2000 Michael Lambert (died 2004); one adopted son, two adopted daughters; died 17 July 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments