Trooper Fred Smith: Soldier who helped liberate Belsen-Bergen

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.During a local truce on 15 April 1945 after fierce fighting along the Rhine, Trooper Fred Smith, one of Montgomery's "Desert Rats" who had fought through North Africa and later Normandy, thought he had seen all the horrors of war. Hitler's men were on the run, Smith's 7th Armoured Division were pushing towards Hamburg and Berlin and he was confident he'd soon be back in London's East End

But that day was to change his life. After the Germans had asked for the truce, he was sent into a concentration camp, near the town of Celle in Lower Saxony, which became known as Bergen-Belsen. There, he encountered hell on earth. A reconnaissance patrol from the 1st Special Air Service (SAS) had gone into the camp first – to free a POW from the regiment – but quickly moved on. It was left to the British 11th Armoured Division and a unit of Canadian allies to liberate the camp before men of the 7th were sent in to help deal with the thousands of dead and dying inmates, many of them Jews but many of them Soviet or other prisoners of war. The Germans had asked for the truce because they feared rampant typhus in the camp, which had killed at least 35,000 inmates, could spread to their troops and (they added to make their point) to the advancing allied forces.

Smith later said: "Approaching Belsen, we knew immediately something was not right. I'd been on many battlefields and I knew this wasthe smell of death. We asked thelocal German civilians what had happened but they were in complete and utter denial."

He and his comrades found some 60,000 inmates, most of them seriously ill, but also 13,000 unburied corpses. "You could hardly tell who was alive and who was dead," Smith said. "We were afraid to lift people up in case they fell apart." One of those who had died only weeks before the liberation was Anne Frank, whose diary would eventually move the world.

The great BBC correspondent Richard Dimbleby, who was with the liberating troops, famously reported on radio: "Here over an acre of ground lay dead and dying people. You could not see which was which. The living lay with their heads against the corpses and around them moved the awful, ghostly procession of emaciated, aimless people, with nothing to do and with no hope of life... Babies had been born here, tiny wizened things that could not live... This day at Belsen was the most horrible of my life."

Smith and his British comrades quarantined the camp, buried the dead in mass graves and tried to save the living by fumigating and feeding them before moving them to a nearby evacuated German Wehrmacht barracks for further treatment. The Brits gave the survivors their bully beef from army rations, skimmed milk and what they called Bengal Famine Mixture, based on rice and sugar, but these proved too rich for the starving inmates. In spite of the British troops' efforts, more than 13,000 more Belsen inmates died in the weeks after the camp's liberation.

"Because the German civilians in nearby towns were still in denial, we took them to the camp to see what had happened," Trooper Smith recalled. The arrival of a Jewish British army chaplain, the Welsh Rev Leslie Hardman (obituary, Independent, 21 October 2008), two days after the liberation, brought a welcome spiritual relief to the surviving Jewish inmates. Hardman persuaded the British troops not to bulldoze the cadavers into mass graves but to take time to bury them with "the dignity in death of which they had been robbed in life."

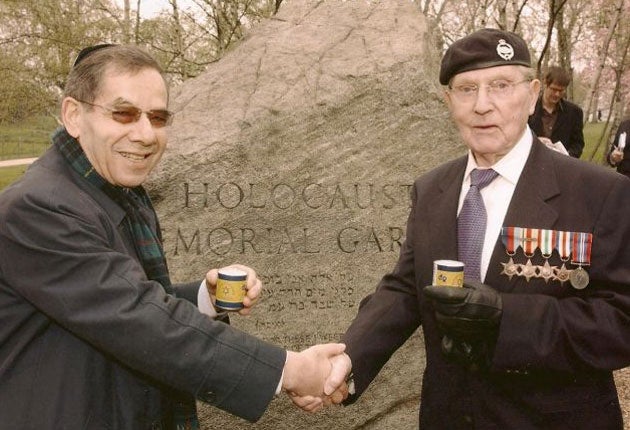

After Belsen, Smith took part in the liberation of Hamburg then pushed on to Berlin, where British forces held back to leave the liberation to Stalin's Soviet forces. On 15 April, 2005, on the 60th anniversary of Belsen's liberation, Smith attended a Holocaust Remembrance service in Hyde Park, where he met a former Belsen inmate, Rudi Oppenheimer, who had been freed from Belsen as a 14-year-old boy.

Frederick Smith was born in Bethnal Green, in London's East End, in 1915, and went into carpentry and furniture-making. After being called up in September 1940 and, after training on Salisbury Plain, he joined the 4th County of London Yeomanry, which was soon drafted as part of the 22nd Armoured Brigade to fight the Nazis in North Africa. The brigade, in turn, was assigned to the 7th Armoured Division, the "Desert Rats."

Smith – Trooper 7917726 – fought in most major battles in North Africa, including Operation Crusader to relieve Tobruk, the two major battles at El-Alamein, the heavy defeat at Sidi Rezegh, the battles for Tripoli and the capture of Tunis. He was shot and wounded near Tripoli in January 1943. During his recovery, an RAF pilot friend from 213 Squadron took him for a rare and highly irregular spin in a captured Luftwaffe Stuka dive-bomber near Sidi Haneish. The pilot offered to do a vertical dive but Smith declined, having seen too many such dives from the ground.

After recovering, Smith sailed with his unit to Salerno and fought with them through Italy, including at the River Volturno, before they were recalled to the UK to prepare for D-Day. They landed at Gold Beach, Arromanches on the evening of D-Day – 6 June 1944 – and engaged in fierce fighting on the drive to the town of Villers-Bocage and the subsequent Operation Goodwood around Caen.

After the war, Smith saw that his fellow Londoners were desperate for "half-decent" furniture and went back to his old trade, starting off in the front room of his house near London docks, using black-market timber. He built his business into one of the largest cabinet-making companies in London, employing 45 staff. In 1973, he treated himself to a "Roller" – a Rolls-Royce, his pride and joy.

Fred Smith is survived by their sons, five grandchildren and three great-grandchildren.

Phil Davison

Frederick Smith, soldier and cabinetmaker: born London 21 July 1915; married 1941 Doris Crabb (two sons); died Chigwell, Essex 11 June 2011.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments