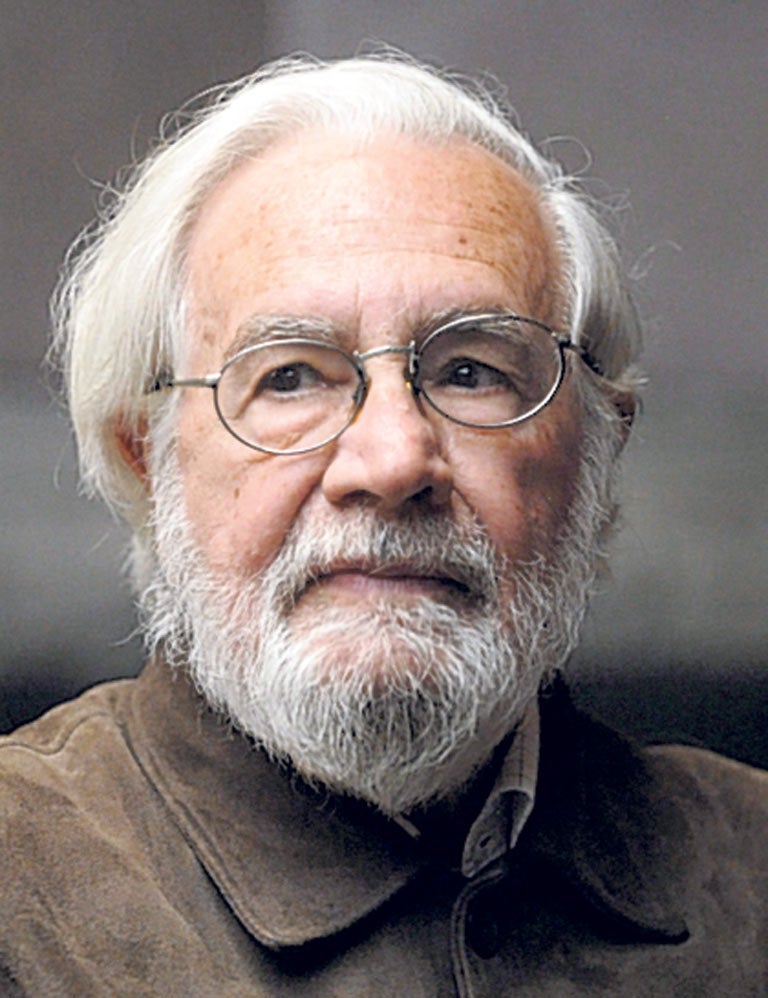

Tomás Segovia: One of Spain's 'poets in exile' during the Franco dictatorship

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I'm sadder than a drowned shoe, sadder than the sweat of the ill ... as sad as the first bus of the day when dawn breaks, as sad as a lawyer's underpants," runs one of Tomás Segovia's poems, and this curious, compelling mixture of the lyrical and the drily humorous, the melancholic and the romantic, helped make Segovia one of the most outstanding of the so-called "poets of exile" during Franco's dictatorship, and a key figure in modern Mexican literature.

He was born in Valencia in 1929 – "my mother was in the city by chance, and I decided to join her," was how he put it. His family were keen supporters of the Spanish Republic. Following Franco's victory in the civil war the family were forced into exile, in Paris then Casablanca, before settling in 1940 in Mexico, one of the few countries to provide outright support to the Republic, even in defeat. There, he joined the College of Mexico, as student then teacher.

He quickly became part of Mexico City's intellectual scene, founding the magazine Presencia in 1946 when he was still in his teens. He then directed the journal La Revista Mexicana de Literature (1958-63), and subsequently collaborated with two more leading Mexican literary publications, Plural and Vuelta – the latter co-founded by him with Octavio Paz.

Segovia was adamant that exile did not define his poetry, saying, "having a rootless existence only means I don't believe in roots". However, it can hardly be chance that absence and nostalgia are two constants in his strongly sensual verses throughout his 40-year exile, and even beyond. In Sonetos Votivos ("Votive Sonnets", 2005), he wrote: "I know that you don't know that I remember so much ... Your sticky, pale skin, kneaded with fever and the moon".

He was 23 when his first collection of verses, La Luz Provisional ("TheProvisional Light") was published,and with works such as El Sol y SuEco ("The Sun and his Echo", 1960)and Anagnórisis ("Recognition", 1967) Segovia established himself as oneof Mexico's most important 20th-century poets.

His lyrical, ironic style captured him many prizes, among them the 2000Octavio Paz Prize for Poetry and the Essay, and the 2005 Juan Rulfo Prize, the most important in Latin America. However, the praise seemed incapable of going to his head, to the point where he once said: "I almost always earned a living honestly: in other words, not as a writer."

This was no exaggeration. Frenetically active, Segovia was equally talented as a translator – Shakespeare,Foucault, Nerval and Ungaretti allprofited from his clear, taut style – and was a gifted printer and carpenter, sometimes publishing his own books orhappily knocking up cupboardsfor many an impoverished artist who would blanch at the sight of a screwdriver or chisel. He also worked as a critic, essayist, diarist, and was, at the age of 80, a keen blogger.

After Franco's death, Segovia – after spells as a professor at Princeton and Maryland – set up a second home in Madrid, and he could often be seen writing his poetry in the well-known Café Comercial, saying "I need noise to concentrate". Despite a heart attack in 2007, his writing continued unabated, and even last spring when his latest work, Estuary, hit the bookshelves, his next manuscript was already sitting on his publisher's desk.

When Segovia died last week from cancer, the senate in the Mexicanparliament held a minute's silencein his honour. In Spain, CarmenCafferel, director of the CervantesInstitute said: "With his death we've lost one of the great reference points for what has been called the 'generation of exiles'. Even though he spent more than half his life in exile, which affected all his writing, he knew how to keep his connection with Spain without bitterness."

Concepció* Reverte Bernal, a professor of Hispano-American literature at the University of Cadiz, addedthat above all Segovia would be remembered "as an excellent poet in a land ofgreat poets".

Alasdair Fotheringham

Tomás Segovia, poet, essayist and translator; born Valencia 27 May 1927; married 1953 Inés Arredondo (divorced 1965; (two daughters, one son), secondly Michelle Aban (one son), thirdly Maria Luisa Capella; died Mexico City 7 November 2011.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments