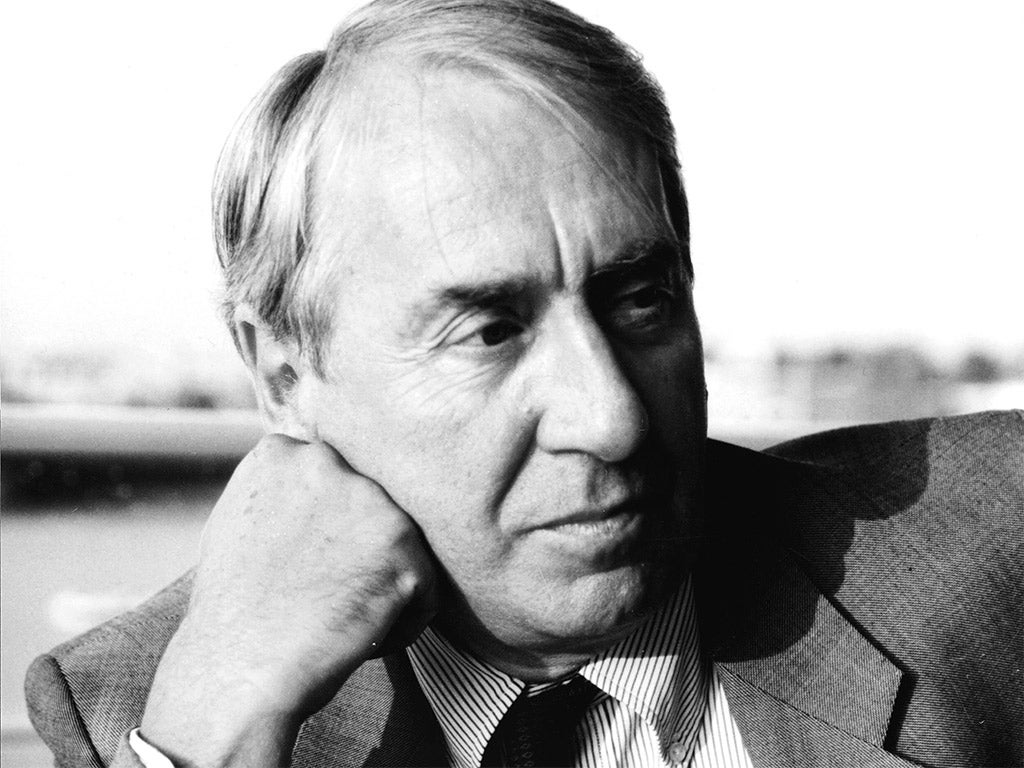

Tom Read: a tribute to the radio producer who helped develop BBC’s documentaries of the 70s and 80s

His calmness and concern made working with him a delight

If the Second World War and its aftermath witnessed the golden age of radio news reporting, the 1970s and 80s were its silver age of documentaries. With a host of talented journalists and an audience reaching millions across the globe through the home channels, the World Service and Radio Long Wave, BBC radio was the international voice of Britain and the epitome of informative features.

Tom Read was a key figure in the development of English language programmes for the World Service – as a producer in current affairs, editor of the flagship documentary programme Analysis, and then as head of central talks and features.

He was the eldest son of the war poet and champion of modern art Herbert Read and his second wife, the musician Margaret Ludwig, with whom Herbert had eloped while they were both at Edinburgh University. Theirs was a classic union of English reticence and continental vivacity – he, the son of a North Yorkshire famer, an anarchist and firm atheist; she, a Roman Catholic convert of German descent with a love of company and occasion.

Read spent his early years near Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire, where his parents decamped to an arts and crafts house during the war years, and then in the North Riding, near where Herbert had been born and now returned for the remainder of his life. The deal seems to have been that Margaret accepted a life deep in the country, where Herbert would devote himself to his writing and public obligations, while she in return could arrange music festivals and organise the children’s education on Roman Catholic lines.

While never with the fervency displayed later by his novelist brother, Piers Paul Read, Tom remained true to the faith taught at Ampleforth College throughout his life. To the disappointment of his parents, however, he never pursued either of their courses of art or music. On graduating from Leeds University and doing national service as an ordinary soldier, he instead chose journalism as a career, joining the Daily Mirror as a trainee journalist, before becoming their first full-time education correspondent.

He moved to the BBC in 1967, first as a scriptwriter and producer in news features and then to the reorganised current affairs department. He eventually became editor of the flagship Analysis and worked on a series of programmes with the formidable Mary Goldring, winning the Sony Award for best documentary for a programme on post-recession Britain in 1985.

In the BBC he found a natural home. With his father’s calm and sense of public duty, coupled with a newspaperman’s fascination with events and gossip, he made the perfect producer. Working with him was a delight: the research and the interviewing were always fun, while his calmness and concern ensured the final broadcast was completed with a sense of achievement which more febrile producers could never manage.

His talent for administration with a human touch inevitably drew Read into senior management and the structural reorganisations which have dominated the ever more corporate BBC over the last decades. In 1984 he went over to Bush House, where he became head of central talks and features for the World Service. It was a place he loved, with its interplay of cultures, languages and eccentric specialists.

He drew equal delight in the even more eccentric world of spies and intelligence when he became general manager of the BBC’s monitoring service at Caversham. The security vetting for the job drew friends and acquaintances into a nether world of interrogation in which intelligence officers seemed intent on establishing whether male friendship meant something more. The job entailed a major reorganisation to fit the service for the modern world, but for Read, its chief pleasure was in meeting the “spies” of the Foreign Office Intelligence and MI6 as well as the visits to the CIA in Langley.

Read had too many interests to wilt in retirement, but his last years were blighted by illness, first with cancer and then, 13 years ago, by the onset of progressive supranuclear palsy, a wasting disease which gradually shuts down the muscles, until Read could neither open his eyelids or speak.

It might seem callous to say that his dying became him, but the extraordinary thing about Read’s decline was that far from it becoming an embittering occasion, he made it an inspiriting one. It was partly his faith, solid rather than demonstrative, which instilled in him acceptance. It was partly the support of his family of three sons and seven grandchildren and, above all, his wife, the artist Celia Read, with whom he had a quite special relationship of loving and mutually respectful intimacy.

But it was also Read himself who made his illness not a challenge to be surmounted, but an opportunity to be pursued. Too little is written about the long road of physical decline which is such a feature of modern old age. But it need not be diminutive. Marshalled by a group of dedicated carers, he was taken to join in the Dance for Parkinsons programme run by English National Ballet, and the Sing for Joy sessions and the art classes organised by the Marie Curie hospice.

Thomas Bonamy Read, journalist and BBC executive: born 12 December 1937; married Celia Vaughan-Lee (three sons); died London 22 September 2015.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks