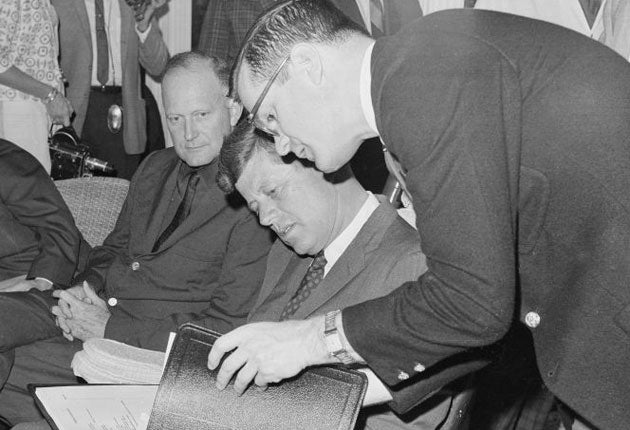

Theodore Sorensen: Speechwriter and adviser who provided the intellectual backbone of Kennedy's 'Camelot'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Ted Sorensen was not just the sole remaining survivor from the innermost circle of the Kennedy White House, a last knight of America's mythical 20th century Camelot. Nor was he only perhaps the greatest and most influential presidential speechwriter of any era. In fact, as was conveyed by his official designation as special counsel and adviser to JFK, Sorensen was far more than a wordsmith, however exceptional. At moments of crisis, when fateful choices had to be made or bold decisions taken – be it the civil rights struggle, the climax of the Cuban missile crisis or the mission to send a man to the moon – he was involved.

"If it was difficult, Ted was brought in," said Robert Kennedy, arguably the only member of the administration who was closer to his brother than Sorensen. John Kennedy himself referred to his adviser as "my intellectual bloodbank."

On the face of it, they were an odd combination: the dazzlingly handsome and well-connected scion of New England wealth, a Harvard-educated war hero – and the sober, somewhat earnest law graduate from Nebraska, of half- Danish, half-Russian Jewish stock, who had never left the Midwest until he went to Washington in 1951, aged 23 and without contacts, only the dream of a career in government.

But in the words of the historian Arthur Schlesinger, Sorensen's friend and fellow Camelot insider, Kennedy and his indispensable aide "shared so much – the same quick tempo, detached intelligence, deflationary wit, realistic judgment, candour in speech, coolness in crisis – that when it came to policy and speeches, they operated nearly as one."

After working for 18 months as a lowly government lawyer, Sorensen was taken on in January 1953 by the newly-elected junior Senator from Massachusetts, who even then was harbouring ambitions about a White House run. The first serious words Sorensen produced for his new boss consisted of an economic development programme for New England, which Kennedy expounded in his first three speeches on the Senate floor.

That, however, was merely the start. The partnership quickly grew close – so close that when the future president's Profiles in Courage won the Pulitzer Prize for biography in 1957, Sorensen was alleged to have beenthe real author. Both he and the Kennedys flatly (and litigiously) denied the charge. But Sorensen's contribution was, to put it mildly, considerable, and Kennedy made over to him a large share of the royalties.

By then, of course, Kennedy's sights were clearly set on far greater things, and Sorensen accompanied him ashe travelled the country, preparingthe ground for his 1960 candidacy.In the early stages, it was often justthe two of them, alone on the road.But the process was crucial. "Everything evolved in those three-plus years," Sorensen would remember. "Hebecame a much better speaker, I became more equipped to write speeches for him."

And what speeches they would be. During his 34 months in the White House, Kennedy delivered some of the most memorable words of any president, including the immortal 1961 inaugural and addresses on the nuclear arms race and civil rights, as well as his speech in Berlin in June 1963. The final versions might have been Kennedy's, but the input of his speechwriter, with his uncanny instinct for language that seared an idea into the public imagination, was huge.

For Sorensen however, his most important text was a private one: the letter he drafted for Kennedy to send to Nikita Khrushchev at the most dangerous moment of the Cuban missile crisis in October 1962, as calls by hardliners for an invasion of Cuba, or an attack to take out the Soviet sites on the island, were becoming ever louder.

"Time was short," he later told The New York Times. "I knew that any mistakes in my letter, anything that angered or soured Khrushchev, could result in the end of America, maybe the end of the world." In the event, the letter, urging a peaceful solution, seems to have been pitch-perfect. The Kremlin leader agreed to withdraw the nuclear missiles and the crisis was over.

Barely a year later came even greater trauma, the assassination of the leader Sorensen idolised. He offered his resignation immediately, but was persuaded to stay on by Lyndon Johnson and in fact helped write the incoming president's first State of the Union address. On 29 January 1964, however, Sorensen became the first member of the former Kennedy team to depart the new administration.

He would spend most of the rest of his life as a senior partner at a leading New York law firm, but never lost touch with Democratic politics – and Democratic presidents. In 1965 he published a best-selling biography of his hero, entitled simply Kennedy, and three years later worked on Robert Kennedy's White House campaign until it was cut short by another assassin's bullet.

In 1970 he made an unsuccessful bid for the New York Senate seat once held by RFK, and was nominated by Jimmy Carter to head the CIA – until it emerged that after the Second World War, a youthful Sorensen had registered as a conscientious objector. Later Bill Clinton, trying to wrap the Camelot mantle around himself, sought out Sorensen. In 2007, however, the liberal elder statesman became an early supporter of Barack Obama's White House candidacy.

Nothing, though, compared to the past, and the years when he rose with a privileged but ill-starred family to the summit of American power. In Counselor: A Life at the Edge of History, his elegant, searching memoir of 2008, Sorensen admitted that "when the Kennedy brothers died, it robbed me of my future."

Theodore Chaikin Sorensen, speechwriter, political adviser and lawyer: born Lincoln, Nebraska 28 May 1928; Special Counsel and political adviser, White House 1961-1964; married three times (three sons, one daughter); died New York City 31 October 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments