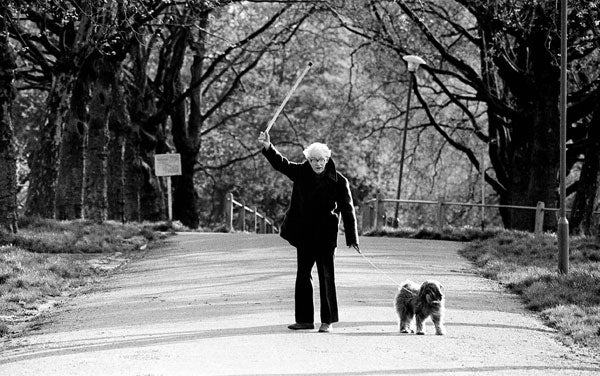

The Year in Review: Michael Foot

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Michael Foot was almost devoid of personal ambition, which is rare in a politician of first rank. He had been Liberal President of the Oxford Union and then Labour candidate in a by-election at the age of 22. Yet he had reached the age of 60 before he took office as Minister for Employment in Harold Wilson's last government. Two years later, when Wilson resigned, the left backed Foot for the leadership of the party – and not only the left. Had he won, he would have become Prime Minister, but he lost to James Callaghan by 39 votes. As runner-up, he was offered his choice of portfolio and he chose to become Leader of his beloved House of Commons, the least administrative and most political of governmental posts.

After Labour's defeat in 1979, Callaghan remained leader of the party for a year "to take the shine off the ball" and give Denis Healey a chance to succeed him. The parliamentary party, however, chose Foot, believing that he, with his "soft-left" approach, might reconcile its bitter divisions. He failed to do so. The task was beyond anybody.

When he was within a week or two of 70, he led the party into the disastrous defeat of 1983 and then, to everyone's relief, including his own, he retired to the back benches and his books. He was still loved and respected. He had sought none of these high roles. They had been awarded to him, sometimes even thrust upon him, because of his personal virtues, his kindliness, his verbal skills, his scholarship and his charisma. I never heard Foot speak ill of anyone outside the context of politics, but inside that context he took an unholy delight in the traditional asperities of the democratic platform and many people thought of him wrongly as a bitter extremist.

Disunity and extremism had led the Labour Party to choose Foot as leader in 1980 when Callaghan resigned. The Labour rank and file had been disappointed by the meagre achievements of 1974-79, oblivious of the problems of a minority government in a world financially destabilised by the oil crisis. The bitterness of the defeat strengthened the campaign of the far left to convince members they had been betrayed by their members.

He became leader by 139 votes to 120 but was unable to preserve the party's precarious unity. He was still a unilateral disarmer, still opposed to the Common Market. The unease of the right wing was brought to a head when the special conference at Wembley decided to give MPs only 30 per cent of the votes in the electoral college. They lost hope in their ability to win over the party and David Owen, William Rodgers and Shirley Williams joined Roy Jenkins in the creation of the SDP. Labour had split at last.

I first met Foot in the spring of 1940 when I joined the Evening Standard. He was 27, the leader writer, and already he had a reputation. Frank Owen took me to the secluded corner where Foot worked alongside the "Londoner's Diary" men, a British peer and a Central European count. "Michael's a Stalinite," said Owen, "I am a Trotskyite" – pressing a copy of Trotsky's My Life on me, saying that nobody who had not read Trotsky was fit to work on this old Tory paper.

In this light-hearted corner, Foot flourished. When they differed on policy from Beaverbrook, Owen and Foot would concoct a leader on the traffic problem of London or some minor aspect of the war effort. Once, Foot beseeched the readers to dig their vegetable plots, dig them wide and "dig for victory", thus providing one of the Second World War's best-remembered slogans. The paper was surprisingly different from Beaverbrook's Express. "Drive me to the scarlet Standard," the drama critic Hannen Swaffer would say to a taxi driver.

Foot, slim, formally dressed, eyes gleaming with fun behind his spectacles, wrote by hand, mouthing his phrases. Like his father, he kept commonplace books in which he recorded favourite passages from Silone, Michelet, Swift, Paine, Byron, Cobbett and Hazlitt, about whom he was to write frequently. Once I noted the series of late-evening meetings with Owen and Peter Howard, "Crossbencher" of the Sunday Express. I told Owen that all London was asking who was "Cato", the author of Guilty Men – a Left Book Club diatribe attacking the Tory ministers who had taken us unprepared into war.

"Find out," he said. It was weeks before it dawned on me that the book had been conceived and some of it written before my eyes.

JOHN BEAVAN, LORD ARDWICK

Born 23 July 1913; died 3 March 2010.

Lord Ardwick died in 1994

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments