Studs Terkel: Broadcaster, author and oral historian who recorded blue-collar life in 20th century America

Mention the name of the interviewer and broadcaster Studs Terkel, who spent most of his life in Chicago, and it invariably brings to mind an inveterate chronicler of blue-collar, hardscrabble America – such books of oral history as Race, Division Street, Working and Hard Times. In fact that quintessential American owed this turn in his career, at the age of 55, to the English actress Eleanor Bron – while Dame Ivy Compton-Burnett proved as sage an inspiration to him as his friends Big Bill Broonzy and Mahalia Jackson.

Terkel, the last of three brothers, was born in 1912 in a diversely populated Bronx, where his parents Samuel and Anna had arrived from the Polish/Russian border at the beginnng of the century. A tailor and seamstress, each highly skilled, they were always at loggerheads, she a volatile and abusive character, he beset by the poor health which left him all the morevulnerable to her vituperation. Terkel – named Louis – shared a room with his bedridden father, but shut much of this from his memory, as he did teenage grief at his father's death, preferring to recall the jazz and drama encouraged by his older brothers.

By this time, with business thin, the family had been transplanted to Chicago, where Samuel's well-off brother-in-law installed Anna as manager at one of his rooming hotels, the Wells-Grand, whose lease she later took. If this hardly fulfilled her dream of what a new life in America meant, she worked assiduously, even blow-torching bugs from bedsprings. The place brought Terkel in contact with its diverse residents, including a hooker who plied her trade at premises elsewhere, and such was the character of Chicago that one classmate's uncle was found "floating down the drainage canal. And no water wings. It was a strange place for him to have gone swimming. The waters were polluted even then".

At McLaren High School he relished debates and poetry, along with Paine, Voltaire and Upton Sinclair – and found a particular penchant for Roget's Thesaurus, which he enjoined upon people ever after.

Although he had not been especially aware of the Crash, its effect began to be felt at the hotel, whose denizens now lingered over card games in the lobby before quietly vanishing. Prospects did not look good for anything that might follow his stint at the city's University, to which he walked each day, lingering en route at the "gallimaufry" shops for jazz records. Subsequent studies at Law School were desultory, by which time this prospective attorney was known as Studs. Mindful of his poor health, he wanted a more macho persona, and had adopted Studs, hero of James T. Farrell's Young Lonigan (1932): by the time its sequels chronicled decline and suicide, Terkel was unshakably Studs.

By 1934 he had a minor civil service post, but with the New Deal he joined the Federal Emergency Rehabilitation Administration to determine the nature of unemployment in large cities while himself hankering after some other job. He did not know exactly what, but he had once appeared, in a fedora, on the cover of American Detective. This taste for acting and being "caught up in the radiance of commitment" led to his joining a theatre group: at a time of civil dispute, he was stopped on the street but allowed to go on his way after explaining that he was due at a play-reading, not specifying that this was Clifford Odets' Waiting For Lefty. These dramatic forays led to appearances in radio soaps, when he was always cast as the villain. "In all instances, I was disappeared," he said. Such decisions were explained to him by the producer: "heroes had pear-shaped tones; mine were apricot-shaped".

Meanwhile, at the theatre, during an adaptation of Ethan Frome, he met a social worker Ida Goldberg, a week older than him. At first she thought he looked like a hoodlum but soon found, she said, as she always would, "he amuses me" – even when, during their courtship, he was always borrowing money from her. In 1939, he claimed that marriage would cancel the debt, and thereafter she was wife and de facto manager.

Hopes of Red Cross work during the Second World War were foiled by his health, and he spent a year with the Army as a radio newscaster (nominally healthier than him, both his brothers inherited the gene which brought their father's early death). Back in Chicago, Terkel was occupied with some more radio work, journalism, and much public speaking: this avowed agnostic could have made a fine preacher, said Mahalia Jackson, whose singing he brought to public attention (never claiming credit for this) on a record show called Wax Museum.

A hard worker, he found that things happened. Particular renown came with Studs' Place, a television programme set in a restaurant where good talk was the main item on the menu. It was struck off the menu in 1953, however, in the McCarthy era, when Terkel's activities were studied. "I'd guess that half the organisations listed by Harry Truman's attorney general as subversive profited to the tune of a buck or two by my windiness," he said. Such had been the success of Stud's Place that visitors thought it existed, asking taxis to take them there.

Times now became hard, a little eased by Ida's taking up teaching, and he disconcerted FBI agents by joshing with them when they turned up. Perforce, he read all the more. This was to sustain the long-running radio show which began to air five days a week a few years later on the city's WMFT station. It became a regular halt for any visiting author. They could reckon on a host who, loathing the "bite" mentality, had closely read their book, its pages heavily underlined, and the conversation – questions unscripted – would form part of a programme which flowed unjarringly from classical to jazz and folk music.

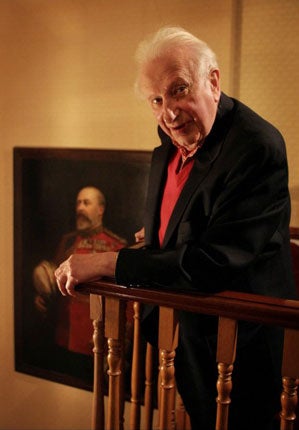

With his cigar, hat and red muffler, he became a familiar city figure, known in every restaurant. Undoubtedly a showman, he was not a megalomaniac: far from villainous, that apricot voice eschewed the cheap shots of confrontation, and drew out his guests, who realised that listeners would not be content with PR banalities. Terkel made no secret that, although agnostic, he well-nigh idolised such people as James Cameron, Jacques Tati, Nelson Algren, Big Bill Broonzy and Bertrand Russell. Of Broonzy he once said, "no matter how humiliating the circumstances, he never allows himself to be humiliated", while in Wales, where he lived, Russell told Terkel, "an individual can do a very great deal simply by expressing an opinion. The powerlessness of the individual is a pretence, an alibi for doing nothing, a form of cowardice, almost".

Such spirits guided Terkel, who none the less found it impossible to say "I love you" to his wife: a consequence, perhaps, of that fraught childhood which could have found a place in the novels of Ivy Compton-Burnett. Curiously overlooked by her biographer Hilary Spurling is one of her most memorable conversations. As Terkel said on meeting the novelist at her South Kensington flat, "hers is not an accusatory tone. It never is. She simply wants to know. Her curiosity encompasses more than life. It's something else she seeks." It was a spirit he shared, and she summed up her work to him: "I think actual life supplies characters much less than art. Life is too flat for that. You must make a clever person cleverer, a stupid person more stupid, and an amusing person more amusing ... Life is merely the mounting block. Don't you think so?"

That is a philosophy which could be considerably elaborated, and Terkel was spurred to do so by Eleanor Bron. When touring America with the revue The Establishment in the early Sixties, she appeared on his show. They got on well, and she later suggested to the publisher Andre Schiffrin, whom she had known at Cambridge, that Terkel should produce a volume of oral history along the lines of a recent success which his firm Pantheon had enjoyed with Jan Myrdal's Portrait of a Chinese Village. Schiffrin was attracted by the idea, and so, in his fifties, Terkel began the works for which he is most widely known (his only other book had been in 1957, for children about jazz).

Sometimes thought simply a matter of putting a microphone in front of a voluble subject, transcription duly shovelled up, oral history in fact requires a shaping spirit as much as any art or trade (a comparison of Boswell's Journals and his Life of Johnson shows that). Terkel reckoned that 60 pages of transcript would yield eight when printed, his final versions tested by being read aloud to his wife. The first volume was Division Street: America (1967), about the cracks and gulfs in the country's society, his aim being – in a phrase from Lillian Hellmann's Watch on the Rhine – "to shake them out of their magnolias".

In working on these books, he traversed America many times, and was as in tune with the contemporary demotic as the New Yorker writer Joseph Mitchell. His books include Hard Times (1970), Working: People Talk about What They Do All Day and How They Feel About What They Do (1974), American Dreams: Lost and Found (1980), The Good War (1984), The Great Divide (1988), Race (1992), Coming of Age (1995), and The Spectator: Talk About Movies and Plays with the People Who Make Them (1999).

The otherwise obscure Lucy Jefferson points out in Division Street: America that, "there's such a thing as feeling tone: either you have it or you don't, you know, it's either horrible or it's friendly. If you ain't got it, baby, you've had it." Dame Ivy it isn't, but it is as pertinent.

Seemingly hefty, the many pages of all these books are highly readable, every paragraph material for a novel: the million-selling Working even prompted a 1978 Broadway musical by Stephen Schwartz and others (a waitress sings of her labours, "It's an Art"), while Arthur Miller used Hard Times for his play The American Clock. Terkel, who regarded himself as a prospector, got to the essence of American preoccupations, and, in letting people speak, drew out more than they realised.

Along the way, among the blue-collar crowd, up pops Joan Crawford, whom he tells he has recently visited a South Africa beset by apartheid, to which she unblushingly replies, "you know, the costumes we wear, Adrian's, they're South African", while Ted Turner reveals, "I've always been a kind of romantic. I feel myself as maybe a modern-day Rhett Butler ... everybody should see themselves as a dashing figure ... I would like to have lived a whole bunch of lives."

One of the most remarkable items is that by CP Ellis, who became business manager of the International Union of Operating Engineers after an early life in the Ku Klux Klan, his attraction to which, and subsequent revulsion from, are chronicled in a way that is affecting. "Deep down inside, we want to be part of this great society," he said – while Arnold Schwarzenegger said of his early years, "everybody gave up competing against me. That's what I call a winner. I own apartment buildings, office buildings, and raw land. That's my love, real estate."

William Benton, who bought Muzak for a song in the Depression and was a millionaire by 36, said, "I have a tin ear. That's why my ear was so good for radio." In The Good War, a stockbroker uncorks his recollections. "It's a terrible thing to say, but it was the most exciting span of time that I ever spent. The most romantic. If you're lucky enough not to get killed or maimed, and you go through it, it's much like a hospital experience. You never remember the pain, you remember the ass of the nurse who came in and bent over you."

A defining moment in contemporary history for him was the 1965 Freedom Movement's march from Selma to Montgomery. Open a Terkel book and one reads on, such is the way he shows, as Russell said, how individual efforts make a difference. When Working appeared, the writer and historian Nat Hentoff recalled, some schoolchildren in Pennsylvania were not allowed to read it after some parents objected to its being a course book; Terkel spoke there, and the book was reinstated. The pupils wrote to him: "you have widened our horizons and you have given us the ability to see what America is truly about".

Although he chronicled all these lives, and was given to talking to himself when nobody else was around, he avoided saying any more than necessary about himself – such as his fame making his son Paul drop any writing hopes of his own, becoming an accountant and changing his name in an attempt to forge a separate identity. But Terkel relished life, and he initially deflected Gore Vidal's 1970 suggestion that he produce a volume on death. No sooner did he begin it – Will The Circle Be Unbroken? (2001) – than his wife died, at Christmas in 1999.

Despite deafness he worked on, certain that his doctor's "ebullience, his spirit of bonhomie, and his skills have been key factors in my living far beyond my traditionally allotted span". A contrast with a fireman in the book, who recalls that "a friend of mine committed suicide by Blockbuster. His wife and his son died. He kept renting videos all day and all night and just drinking liquor, scotch. They found him with the VCR running."

Terkel caught that great American way with words, and, after the subject of death, he turned to Hope Dies Last (2003), which was subtitled, with an echo of Russell's remark, "Making a Difference in an Indifferent World". Inspired by Thomas Paine, it chronicles a new spirit: "Today, from unexpected sources, comes a growing challenge to the official word... It may not be the stuff that makes a TV soundbite, but it's the stuff of neighbourhood. It's the stuff set off by those who stepped forth and made the word 'activist' a common noun in our vocabulary; a new vocation."

Terkel had the spirit to be a part of every era he lived through. Despite doubts about technology, he turned the tape-recorder to brilliant effect. "A decade that could throw up a phenomenon like the Beatles, that was really something, wasn't it?" he said. His favourite song by them was "Hello, Goodbye" – indeed, he was very much of the view "you say goodbye, and I say hello". As he glossed it, "don't ask me why, it just gets to me somehow, it expresses – well, I don't know what: if I did, maybe it wouldn't be as meaningful for me, would it? It expresses the inexpressible."

Christopher Hawtree

Louis "Studs" Terkel, oral historian, writer, broadcaster, actor: born New York 16 May 1912; married Ida Goldberg 1939 (died 1999, one son); died Chicago 31 October 2008.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks