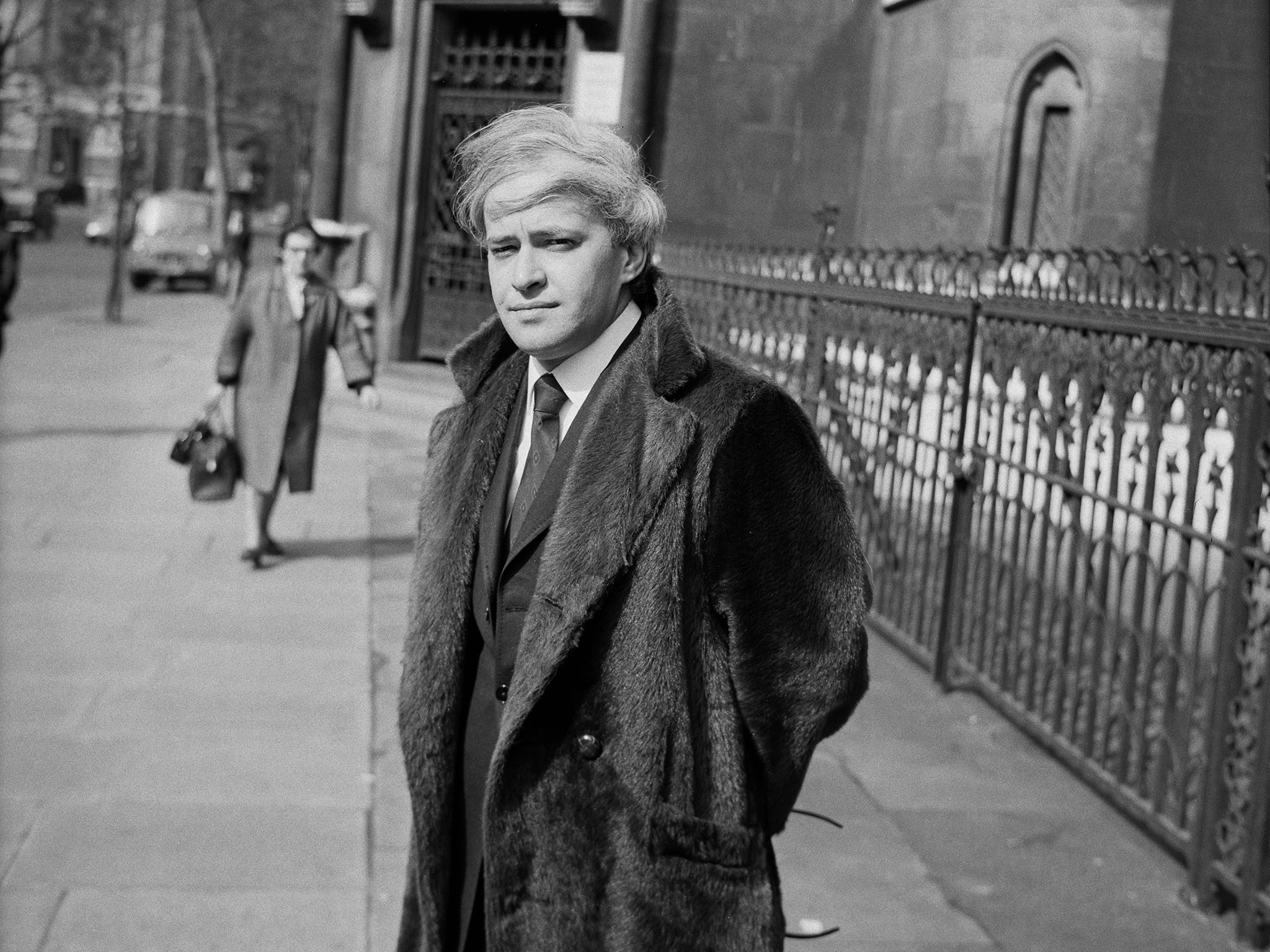

Stephen Vizinczey: Provocative author of amorous bestseller

Before his surprising literary success in an adopted language, Vizinczey wrote several plays and was part of the Hungarian Revolution of the 1950s

Stephen Vizinczey, who drew on his war-torn youth in Hungary in writing an international bestseller chronicling a young man’s romantic experiences with older women, which he wrote in English a decade after fleeing his homeland, has died aged 88.

Vizinczey was two when his father, a village schoolmaster, was stabbed to death by a knife-wielding Nazi.

He was taught by Benedictine monks early in his life and spent much of his youth in the company of his widowed mother’s friends and relatives, and women. By the time he was 12, young Stephen – then Istvan – was helping to procure female companions for US soldiers in Europe and was embarking on the first steps of an erotic education that formed the background of his 1965 novel, In Praise of Older Women. He published the book on his own while living in Canada, and it has appeared in multiple languages over the years, selling at least 5 million copies.

Before his surprising literary success in an adopted language, Vizinczey wrote several plays and was part of the Hungarian Revolution of the 1950s, when a student-led uprising nearly toppled the country’s communist regime. Ultimately, the Soviet Union sent troops and tanks to crush the rebellion, and Vizinczey barely escaped with his life. He ended up in Canada knowing only a few words of English.

“I couldn't read a newspaper headline,” he recalled to Toronto’s Globe and Mail. Hired as a bookkeeper, he proved to be incompetent at the job and later said he became so desperate that he contemplated suicide.

“I was afraid to jump,” he told Newsday, “so I thought starving might be the best way to go. To pass the time while starving, I thought I might as well learn English.”

He found work with Canada’s national film board and later for the Canadian Broadcasting Corp (CBC). In 1960 he edited a short-lived literary magazine that published the poetry of his Montreal neighbour, singer-songwriter Leonard Cohen.

Vizinczey began to weave the experiences of his early years into a novel focused on what he – or rather a literary alter ego named Andras Vajda – had learnt about life and love from women.

“Modern culture – American culture – glorifies the young,” Vizinczey wrote. “On the lost continent of old Europe it was the affair of the young man and his older mistress that had the glamour of perfection.”

The central character of the short novel is a Hungarian-born philosophy professor. The book touches on the terror of the Nazi years and the repression imposed by communism, all filtered through a sense of longing for a sensuous and irretrievable past.

The book describes how young Andras learns about literature, music and the arts of love from a series of women, ranging in age from roughly 35 to 50. He has his first sexual experiences at 12, then at about age 15 begins a romance with a married woman named Maya.

“One of my chief irritations at the time was the blankness of the faces of my young girlfriends,” Vizinczey wrote in the novel. “But Maya’s face, with the fine lines of her 40 some years, expressed all the shades of her thoughts and emotions.”

The novel’s subject matter and its frank treatment of sex proved too explosive for mainstream publishers. When he received a top bid of $250 for his book, Vizinczey decided to publish it on his own.

“I borrowed the money,” he told the Toronto Star in 2004, “quit my job at the CBC and worked for three months on the launching, driving around in my car delivering the books. Everyone said I was crazy.”

The novel’s picaresque hero was likened to Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones and Stendhal’s Julien Sorel, and each of the 17 chapters had an instructive title reminiscent of 18th-century literature: “On War and Prostitution”, “On Becoming a Lover”, “On Don Juan’s Secret”.

The scenes were more suggestive than explicit, yet some readers condemned In Praise of Older Women as pornography. Other reviewers found literary merit in the tale, including The Sunday Telegraph’s Isabel Quigly, who wrote that it was the rare “novel which is funny – as well as touching about sex ... elegant, exact, and melodious.”

The book instantly became a bestseller in Canada and Europe, but Vizinczey turned down an offer from Random House, which he came to regret. He went with a smaller publishing firm, which sold the rights to a cheap paperback publisher of potboilers. The novel received little attention in the United States until it was republished in the 1980s.

In Praise of Older Women has been filmed twice, including a 1978 adaptation starring Tom Berenger and Karen Black and a 1997 Spanish-language version featuring Faye Dunaway.

Contentious and protective of his work, Vizinczey battled with agents, publishers and filmmakers and filed at least two lawsuits over unpaid royalties. His suit against publisher Ian Ballantine dragged on for years.

“My father was killed by a Nazi,” Vizinczey said in 1985. “I was once in danger of arrest and torture by communists. But I never personally knew evil men until I got involved with New York attorneys.”

Istvan Viziniczei was born 12 May 1933, in Kaloz, Hungary. His father, a teacher and opponent of fascism, was stabbed to death at his desk in 1935. His mother later became an office worker.

Vizinczey studied philosophy, literature and music at a Budapest university and at what was then the Academy of Drama and Film in Budapest. His first two plays were banned by the Ministry of Culture for “anti-socialist tendencies”. He had sold the film rights to a third play, about a family’s internal disagreements, which was broadcast on radio and was scheduled to open at Budapest’s National Theatre in 1956, when it was shut down by the authorities.

“I was tasting fame and glory, and I had more money than I knew what to do with,” Vizinczey later told the reference work Contemporary Authors. “The only thing missing was a free country to write in, so I fought in the revolution. A month later I was a refugee without a country and a writer without a language.”

Vizinczey, who changed the spelling of his name after arriving in Canada, became a prolific critic and reviewer and published two collections of essays. His second novel, An Innocent Millionaire (1983), about a young man who finds a sunken treasure only to encounter modern-day pirates in courtrooms and the antiquities business, was praised by novelists Graham Greene and Anthony Burgess. A final novel, If Only, was published in 2016.

Vizinczey had an early marriage in Hungary that ended in divorce. In 1963, he and a CBC colleague, Gloria Fisher Harron, were married. (He sometimes noted that she was more than six years older.)

“She was my editor, critic and researcher,” Vizinczey wrote in a blog post after her death last year. A stepdaughter, Martha Harron, died in May.

Survivors include another stepdaughter, filmmaker Mary Harron; a daughter from a relationship with British author Angela Lambert; and two grandchildren.

By 2010, the early shock of Vizinczey’s first novel had subsided, and it was published anew as part of the Penguin Classics series of literary classics.

“I wonder what kind of life I would have had if it hadn’t been for my mother’s tea-and-cookie parties?” Vizinczey wrote in In Praise of Older Women. “Perhaps it’s because of them that I’ve never thought of women as my enemies, as territories I have to conquer, but always as allies and friends – which I believe is the reason they were friendly to me in turn.”

Stephen Vizinczey, writer, born 12 May 1933, died 18 August 2021

© The Washington Post